Procreate Project, the Museum of Motherhood and the Mom Egg Review are pleased to announce the 42nd edition of this scholarly discourse intersects with the artistic to explore the wonder and the challenges of motherhood. Using words and art to connect new pathways between the academic, the para-academic, the digital, and the real, as well as the everyday: wherever you live, work, and play, the Art of Motherhood is made manifest. #JoinMAMA #artandmotherhood

July 2020: Art by Afrooist, Words Wendy Carolina Franco

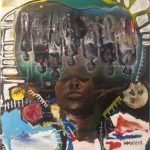

Art by Sunshine Negyesi aka Afrooist

She works across different media, ranging from live performances, painting and sculpture- using the poetry of hammering, beating, pulling, teasing and breaking, to express how her life has been lived and soaked in contrast. Her earlier works try to understand her black identity as it has been interpreted by society embracing the conflict revealed within the final pieces reflect the beautiful ugly of existence, that which is both attractive and repulsive, disquieting and squeamish, setting the viewer in an entanglement of something mucky, gritty yet sublime.

Born in London 1983 , Afrooist was raised in a biracial family in Tooting, South London. Her mother is Filipino and father from Guyana . She studied classical studies at Warwick University ( 2005 ) and trained as an early years teacher at Greenwich University ( 2016 ). Artist and singer, she began as a self taught painter, and developed the ability to deconstruct and reflect on her practice whilst studying Fine arts at City Lit London (2018). During the Summer of 2019 Afrooist made her debut solo exhibition at The Ritzy Brixton which included a live art performance ritual framed around a character she named Black Persephone in musical collaboration with Tanc Newbury and Siemy Di. A mother of 2 children, she strives to be the change she wants to see in the world. She is Co-founder with Dirish Shaktidas of a project called Futureseeds and is currently residing in South West London.

Words by Wendy Carolina Franco, PhD

A Body Other Than My Own

* This essay talks about the video of the murder of George Floyd.

When the day’s headlines about Covid-19’s devastating impact on the Black community were replaced with images of Black youth screaming next to burning cars, I reacted with fear. I was in full support of the protests but scared for the protestors. My 13-year-old twin sons felt that watching the video of George Floyd’s death was necessary for me to understand the rage in the streets. P said, “If you don’t see how he was killed, you are being a coward.” I replied that decades of seeing black people suffer changed nothing and only normalized seeing black bodies being abused. They chewed on that for a minute. My teenagers have plenty of complaints about me, but they respect my opinions on social and political issues.

I am a Dominican woman with a history of serial migration, meaning that my mother immigrated first, we reunited when I was twelve, and one year later, she was imprisoned for eight years for a drug-related crime a white person would have barely done time for, and was later deported. I grew up alone in New York City, dropped out of school. I eventually earned a Ph.D. in clinical psychology. Now I specialize in trauma, counseling mostly minoritized people.

“Look,” I told the boys, “watching someone being murdered can be traumatizing to the viewer, and for young people of color, like you, it is particularly harmful to witness racially motivated violence.” Such videos reduce a person’s life to the day they were murdered, I argued. I suggested they focus instead on studying the origins of systemic racism, and—this part is really painful as a mother–on learning how to behave to stay safe. P and F told me they had seen many people of color die, and that their bubble of racially diverse kids had also seen all the viral videos. F said: “I don’t know if it’s good or bad for me to watch these videos, but this is the worst one I have ever seen.”

Still trying to protect my mental health, I asked them to describe it to me. I don’t know about all twins, but my boys talk at the same time and always contradict each other–it’s infuriating. This time, there were zero contradictions. P noted that the police and Mr. Floyd looked so calm that he thought it was fake, then he suddenly got scared for George Floyd. F spoke of moments he thought someone was going to intervene but were stopped. They both described a slow realization that no one was going to help. The killer stayed on top of Mr. Floyd long after his body had gone limp. P concluded that if the officer had just gotten up, Mr. Floyd would have lived.

My face awash in tears, I had a knot in my throat. Avoiding the specifics had been a way of distancing myself from George Floyd’s murder. I still think that watching black people die is traumatizing for Black people and desensitizes non-Black people to their suffering. But the reality is that children are watching.

After my sons brought Mr. Floyd’s death to life, I looked for photos of him. A beautiful vibrant trio in a park summer outing came up. Wow, he was so tall and serious. He looked like a guy who kept his word. That little girl in his arms must have felt like God himself was carrying her. There was enough arm and chest for her to kick back and watch the world from up high. His partner was beaming, enjoying the circle they had created. It looked like a magnetic field, impenetrable and safe.

I decided to watch the video, once.

From watching the video of George Floyd’s death I learned that he was a survivor. Even in the most frightening and compromised state, Mr. Floyd had the wherewithal to control the instincts we all have. He did not fight, or attempt to run, or freeze. These responses to danger come from the most ancient parts of our brain. He mustered the focus to try to de-escalate the situation by reminding the man intent on taking his life that they are both human.

George Floyd said he was in pain, that he couldn’t breathe, communicating that he is human and like all of us will die without oxygen. He tried to calm the officers’ fears. He said he would comply with orders. He tried to adjust his body. He called out “Momma.” This dying man claimed his personhood by calling for his mother. He had profound attachments and a mother who loved him, and there is nothing more human than that. I don’t need to know how Mr. Floyd lived his life. The video of his murder showed his fighting spirit, his focus on surviving for his family, his humility, his dignity. He did not give up, but clearly understood what he was up against.

F knows what it’s like to not be able to breathe. He had pneumonia when he was eleven years old, and a young white doctor refused to take his complaints of difficulty breathing seriously. She said his lungs were clear and sent us home twice. I called my dentist, an old school Peruvian MD, who said, “GET OFF THE PHONE AND CALL 911.” My son was too weak to walk. He was rushed to the ICU where he remained for a whole week. They told me that he would have been dead in one day.

For the local protest, F made a sign that said, “I CAN’T BREATHE.” I was flooded with sadness. He was not copying the rallying cry this sentence has become, he does not know how Eric Garner died, and he was not thinking of the countless COVID-19 patients who suffocated to death, or of the air pollution our way of living creates. As much as he understands, he has no idea.

The pain of Black people only seems to bring about more pain. The Brooklyn protests we went to were completely peaceful and about 50% white, but Black and Brown protesters risk a lot more. They will be arrested and penalized more harshly than their white counterparts. Protesting also poses uneven health risks. Clueless celebrities and people who do not understand systemic racism claimed the coronavirus would be the ‘great equalizer’; instead we learned that racial privilege extends to levels of exposure to the virus and the body’s ability to fight the illness. The data on mortality shows that Black people die at three times the rate of white peers. Why do we accept so much black death?

Being the target of injustice creates a double bind, or a lose/lose situation. If you do nothing,

you suffer psychologically and emotionally, and if you fight back you risk further harm. Yet, I have to be hopeful. I see solidarity for Black people and a focus on action. I too come from pain. I can relate with feeling invisible, unimportant, and forgotten. But I will never know what is like to live in a body other than my own.

We naively think that our shared humanity is enough to experience empathy, but it isn’t, because of antiblack racism. We live in a society that assigns value to people’s lives depending on their identity. In this case, we have seen the repeated dehumanization and abuse of Black bodies, and for generations, we have labored to rationalize a world wherein skin color, gender and sexual identity, religion, place of birth and physical ability are risk factors for suffering and death. The human brain will distort reality to protect us from the idea that bad things happen to good people. As an example, victims of abuse, even in the most extreme cases, find ways to blame themselves. On a psychological level, having provoked the abuse preferable to the idea that something out of your control, like your body, can make you a target of violence. We make sense of systemic oppression by blaming the victims.

To undo lifetimes of mind-bending justifications of a racist system, we need action. Laws force people to adjust their belief systems. But we can go further and explore the barriers that keep us from seeing ourselves and our loved ones in the faces of Black victims of racist violence. Those barriers are constructs like “us and them or good and bad,” that keep us focused on our own suffering and desensitize us to the pain of others.