Review by Carole Mertz

Review by Carole Mertz

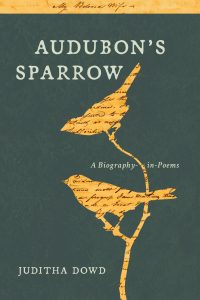

Dowd’s literary Audubon’s Sparrow: A Biography-in-Poems is as delightful and colorful as the famous avian sketches of the renowned bird watcher. The poet records the lives of Lucy and John James via facts and imaginings, told mainly through Lucy’s viewpoint. Actual journal entries by Audubon are set in italics to distinguish fact from fiction. Dowd conveys other narratives through poems and imagined diary entries, as if written by Lucy.

“Monsieur,” the opening poem, (p.3) describes Lucy Bakewell’s first meeting of Audubon, recorded as a diary entry, as if from Norristown, Pennsylvania in 1804.

Today our neighbor at Mill Grove paid us a welcome call.

Belatedly, I add. Had not my father met him Monday

hunting in our woods, would he have come at all?

John James’s French father has placed him in the care of a Quaker family who runs the plantation next door to the Bakewell household. The couple are married in 1808. Dowd’s poetry traces their successes and failures up to the point of their setting sail, in 1830, for England, where together the two will supervise the production of the engraved bird sketches and the promotion of the forthcoming The Birds of America.

Both face many hardships in the two decades leading up to their 1830 departure. After multiple childbirths, only two sons, John and Victor, survive. Lucy is often left alone with them as her husband, whom she calls La Forest, hunts and travels, leaving behind the care of their general store to Lucy and their other partners and / or Bakewell family members. Often, throughout the marriage there is insufficient money, compounded by the fact of the collapse of the economy during the Panic of 1819. The Audubons, as business owners, were directly affected.

In poems rendered simply and generally expressed in the fewest possible words, Dowd conveys the fears and struggles experienced in frontier life. Some of the poems are aided by notes given at the back of the book. Added to these notes are four other useful items of printed matter at the back of the book: A Chronology, a Bakewell-Audubon family tree, a list of works cited, and a list of Image Credits. (Copies of five plates from The Birds of America are interspersed throughout the hundred-page volume along with a copy of the 1826 John Syme portrait of Audubon and a photograph of a miniature of Lucy from ca. 1831.) All of these elements, along with the beautiful cover produced by Rose Metal Press that uses a special font styled after Colonial America-type print, make this an outstanding volume.

The chronological listing parallels events occurring in the nation or the world simultaneous to local events in the Audubon and Bakewell families. The report of the eruption of Mount Rainier in 1820, for example, sits beside the Audubons’ move to Cincinnati where ‘La Forest’ will be assistant to James Mason in the Western Museum, another venture that is to fail. Lucy will be left with the task of collecting back payments while John James departs promptly for New Orleans.

I found Dowd’s poem “A New Season” (p.95) one of the finest in the volume. The last eight lines of the poem follow:

It’s cooler among the trees.

I’ll dismount and take my time

my ease

as may any woman left

to her own care and devices.

Sunlight sparks the trees

their needles on the wind—

let it suffice.

In it, the lines do a bit of wandering on their own, just as Lucy does, and the author’s use of white space serves well to heighten the poem’s carefree quality. This so appropriately accommodates the mood the poem describes.

I am a piano teacher by profession. I found it delightful to consider how, in the early part of the 19th century, Lucy might have taught music to supplement the family income and, indeed, prevent starvation for herself and her sons. (Dowd records this information in the collection; it is likely based on her reading of Carolyn DeLatte’s Lucy Audubon: A Biography.) The poet also refers to Mozart’s The Magic Flute, the tunes of which might have been familiar to Lucy, but surely there cannot have existed an abundance of available pedagogical sheet music. (It is known, however, that Anthony Philip Heinrich published instrumental and vocal pieces in The Dawning of Music in Kentucky in 1820.) One also wonders how many families on the Kentucky frontier were in possession of pianos in those early years.

I grew up on a farm in Bucks County, not too far from the Norristown farm “Fatland Ford,” the homestead of Lucy’s parents. In my early schooldays, my mother taught me to watch for birds and listen to their songs; she loved Audubon and the work he did on identifying and drawing the diverse species and she owned recordings of American birdsongs. Were she alive today, she’d delight in reading Audubon’s Sparrow, as I did. I was sorry to see it end.

Carole Mertz, poet and essayist, has reviewed for World Literature Today, CutBank, Main Street Rag, Mom Egg Review, and elsewhere. She is book review editor at Dreamer’s Creative Writing. Mertz is the author of the poetry chapbook Toward a Peeping Sunrise (Prolific Press, 2019). She resides with her husband in Parma, Ohio.