Review by Jennifer Martelli

In her poem, “Hurricane Necklace,” Rebecca Hart Olander writes

Remember how you made those block cities,

and my boyfriend knocked them down for you with a strand of Mardi Gras beads,

shiny purple wrecking balls you two called a hurricane necklace, before he was

my husband and your day-to-day dad? (2)

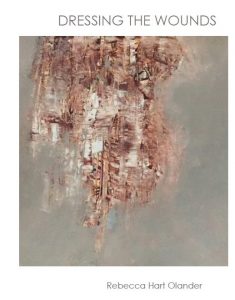

As I was reading, I was moved to read this poem out loud for the joy of sound. This need to hear the poems, to feel them in my mouth, happened throughout Olander’s chapbook, Dressing the Wounds. I was amazed by the poet’s ability to re-imagine and organize sounds and imagery. In a collection that explores and confronts the inherent broken-ness and healing in relationships, Olander consistently presents this fraught nature with poetic, linguistic magic.

Olander’s poems are grounded in the home, in the mundane and sometimes painful duties of motherhood, marriage, and work. And yet, they rise to the level of incantation by this poet’s language. The act of doing the dishes at a sink where “the whorl/and the marble are inextricable,” becomes beautiful and heart-breaking:

I see you bending by the sink

trying so hard to get something

burnt to release itself from

the bottom of a pot. Let it soak

I want to tell you.

(“Watching Love Do the Dishes,” 8)

This burning—one type of destruction—is the fertile groundwork for much of Olander’s poems of healing through language. In the title poem, “Dressing the Wounds,” a poem that asks, “What will it take to heal?” she writes,

The thing that looks charred

provides the burning. The thing that is deformed

provides a healing . . . .

Like vaccination

a portion of poison fortifies against disease. (10)

The opposition of forces, much like a poetic line or a wound opening, is the heart of the book, perhaps the heart of the speaker. In “Double Portrait of Trudl,” this conflict is given mythological context,

Diana and Juno are at odds: hunting vs.

marriage, the moon vs. childbirth.

//

I reach out to you beneath the sheets

my arrows laid aside, fertility on the wane,

both sides of me asking for worship.(13)

Olander makes clear that these opposing forces, whether in the world or in the home, come from within. In “Malum,” the child tells the mother that “the Latin word for damage” is “the same as apple.” The mother reminds herself that “noticing one’s own nakedness can be a loss (4).” The speaker recognizes the danger in self-protection as well, that harm can occur because of one’s own defenses. In “Poetry,” a poem that pays homage to animals, and is, perhaps, an ars poetica, Olander desires to be like the elephant whose “tusks/curl like ivory swords right out of my face” (17-18).

Animals graze, hunt, and roost in Dressing the Wounds. Some live within the home, and their language, regardless of its subtlety, becomes the poet’s language. The bats live inside the walls of the speaker’s home, “Between studs, emptiness./They fill it with nocturnal summer scrapings.” These sounds become “a manifestation of the fact that//what we don’t deal with will surely return/to roost. (“Echolocation,” 30-31).” I adore Olander’s jealousy of these bats as sexy vampires in “Blind,” which is a brilliant and tragic poem about marital estrangement,

This fissure into

which we’ve fallen, with its absence

of touch has me jealous of these fellow

mammals. . . .

or perhaps they feel

their way, bouncing sounds off each other,

boomeranging echoes back and forth

until they locate their desire. (32)

I loved this collection, which is an homage to the split apart and the re-joining, an homage to sound, to poetry. This is a collection to be read out loud, and then, read out loud to a beloved. Like the shattered framed photo in “Reading Tarot Before Our Eighteenth Anniversary,” we are left with “our signifiers in shards. . . .though two faces remain intact and in love. . . .(27).” Rebecca Hart Olander’s collection, Dressing the Wounds, praises how we are

struck

speechless at the warp and weft

of happiness and all its cousins:

contentment, loneliness, and fear

(“ ‘American Bedrooms’ in the Museum of Sound,” 33)

Dressing the Wounds by Rebecca Hart Olander

Dancing Girl Press, 2019

Paper, unpaginated.

Jennifer Martelli is the author of MyTarantella (Bordighera Press), as well as the chapbook, After Bird (Grey Book Press, winner of the open reading, 2016). Her work has appeared in Verse Daily, The Bitter Oleander, Iron HorseReview (winner, Photo Finish contest), Sugar House, Superstition Review,Thrush, and Tinderbox Poetry Journal. Her prose has been published in Gravel, The Baltimore Review, and Green Mountains Review. Jennifer Martelli has been nominated for Pushcart and Best of the Net Prizes and is the recipient of the Massachusetts Cultural Council Grant in Poetry. She is poetry co-editor for Mom Egg Review.