Review by Christine Stewart-Nuñez

Review by Christine Stewart-Nuñez

Before I opened Monica A. Hand’s DiVida to review it, I felt a particular responsibility; Alice James Books published this collection posthumously. Poets work hard to promote their work, and in this regard, DiVida seemed an orphan in need. Reading it deepened my commitment but for a different reason; these poems stunned me to the core. DiVida needs to be read, celebrated, and sung from the rooftops.

It’s not accidental that Whitman’s words bubbled up in my first attempt to describe this amazing book. While there’s nothing barbaric or yawpish about DiVida, Hand’s work is exquisitely democratic, organic, American. In one eight-line poem, she references both Color Me Badd and Herodotus (“DiVida and Brain Man hide out at the Park and Ride”). In another she samples Cameo’s “Word Up,” mentions Parliament Funkadelic, and uses a tarot reading’s structure (“DiVida reads Brain Man’s Tarot at the Shady Oak Trailer Park in Mosquito City”). Even DiVida, the primary persona, contains multitudes: captain of the lacrosse team; peace-keeper; wearer of cotton slacks and lavender ties; heir of Thomas Jefferson; bean-eater. Tussling with another persona, Sapphire, DiVida’s masks become even more expansive, which Hand asserts in the opening poem, “DiVida’s I am’s” (1):

I am crooked petticoat jamboree

a tall girl whose balding bleeds

I am the magistrate’s fool

so smart I do public school

I am a terrestrial body float

ocean the tsunami broke

I am the enemy of the sublime

slow move tractor slime

I am civil service blow

Wall Street man who hugs your dough

I am transformer queer in surplus drag

a woman whose tits sag

These striking juxtapositions anchored by clever rhymes compelled me to reread and savor them. And this poem establishes the book’s tone: smart, sharp, real.

Whitmanian in the broadest sense, Hand’s second collection is unapologetically contemporary. Hand foregrounds race and gender as sites of inquiry, and uses timely cultural touchstones, such as the murder of Treyvon Martin and racial profiling, to respond to abuses of power and white privilege. Social class—under-represented in American poetry—is important, too. In “DiVida lives within her means” (34) Hand’s catalog of unadorned details:

Eats beans

Sleeps on the sofa

Homeschools her progeny

Stuffs cardboard in her shoes

Washes her underwear in the sink

Hand’s shift to anaphora—“We will invest in medical research. / We will invest in clean energy. / We will invest” (9-11)—points to how DiVida’s choices are immediately necessary in contrast to dominant priorities. Hand uses this strategy several times to reveal dissonances present in America today.

Audre Lorde’s concept of “the erotic” –the assertion of creative energy empowered—surface for me often in DiVida, especially in poems that feature desire as power. When the world feels overwhelming, DiVida imagines herself masturbating inside a snow globe: “she comes in a twist and a shout like a blizzard of glass” (“DiVida guns the snow-white light” 46). This incredible simile, ending a prose poem rich with detail but devoid of metaphor until then, demonstrates Hand’s skilled wordsmithing. I also see Lorde’s ideas in the intersectional ways DiVida resists identity reduction. Toward the end, DiVida even embraces transcendent possibilities. “DiVida becomes pine” (69) opens with the description: “evergreen coniferous with needle-shaped leaves woody cones / her thick and sticky sap turpentine her scent voluminous, audible // her arms her legs her buttocks her head her toes something to sit upon / soft like a cushion hard like a frame.” Not reduced to nature, the pine symbolizes timeless endurance: “your plume’s been here ever since this planet was covered in forest / and you really were a tree // a tree surrounded by water.”

Hand crafts each poem in DiVida with consummate care. Punctuation is left out when breath needs pulled through a poem. So, too, Hand omits connective tissue that can drag a line’s music down. Stripping down noise crystalizes these voices. I glimpsed some ghosted forms—moves reminiscent of ghazals, some villanelle-like refrains, a triolet—which strengthen the lyricism of Hand’s verse but keep it decidedly modern.

As Marilyn Nelson notes on her cover endorsement, DiVida is “one voice speaking for a universe of black women.” I’ll close with Hands’ words from “Masks for the madhouse” so readers can listen:

you give me no choice

my choice no choice

visible scar like the blackened eye

bruised arm like the wet bed

wet mop like the very wet panties

deafening quiet like a secondhand hum

a body that builds upon itself

masks the madhouse (4).

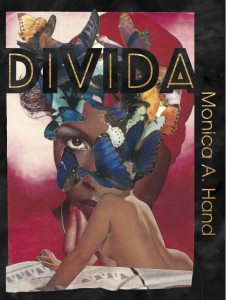

DiVida by Monica A. Hand

Alice James Books, 2018, $15.95

ISBN: 9781938584749

Christine Stewart-Nuñez, essayist and author of four poetry collections, is a professor in the English Department at South Dakota State University. Find her work at christinestewartnunez.com.