Breena Clarke

Fifteen

for Najeeb Walid Harb (1974 – 1989)

He stands behind a screened door, mesh inside a wooden frame, the old kind from the earliest part of my childhood. This iconic door is meant to let breezes through and keep flies out. These doors were always slamming or not slamming depending on how obedient a child was, and gouges in them created breaches where all the flies and other insect pests that harried the hot and humid Washington, D.C. summers in my childhood entered the kitchen to light on the food, the table, the floor. In Syria, his father’s home country, flies were ubiquitous in the summer months also. They swarmed us on the veranda at the family’s home in a suburb of Damascus. I swatted at them furiously. We were sitting outside in Syria, in the morning, watching a woman passing who herded several children who herded a flock of goats. They walked out early to graze her flock and returned at dusk to sell my mother-in-law fresh milk for our yogurt that was milked directly into a large can. The largest boy carrying the full can up to the door. The animal’s hair floating at the top of the milk can.

When my son, Najeeb and I visited Syria forty-two years ago, he was less than a year old, but his cousins called him uncle because he was the first son of a son. Though Syria had a primarily secular and progressive culture then, enviable in the region, women were definitely in the back seat in public life. I had status within the family fabric because of Najeeb, as the mother of a boy. He was my token, my talisman, my badge of honorable motherhood. He was called Najeeb because his father’s father was named Najeeb and had died a month before he was born. I was called Imnajeeb, Mother of Najeeb. I liked that. I thought of motherhood as a vital job that I intended to do well, nay excellently.

Najeeb was on the lip of adolescence when he died accidentally. Just shy of fifteen years. Not enough for me. It is difficult, nearly impossible for me to place Najeeb’s life within a context of it being simply a short one. Because I am so aware of his excellence and his unfulfilled promise I can only think of his loss as devastating. I can just never set aside my goals and dreams for him. The true sadness comes when I must acknowledge I’ve been mourning for these dreams as much as for the child. It is sad, but it is sane.

March 24, 1989. Najeeb has been gone so long that the ache of loss is like an arthritic ache, a deep, painful throb that is nevertheless manageable and responsive to painkillers. I get arthritis, I understand it, I’ve got it.

My framework for future goals was upended completely with Najeeb’s death. I started to write regularly and purposefully because doing so was palliative as well as rewarding. I simply felt better, less sore. Writing was soothing. Directly after Najeeb died, I suffered forgetfulness. I lost keys and was not able to concentrate. I think this is commonplace. I kept coughing up remembrances of things we did together, what kind of person he was. The grief counselor suggested that I write out these snippets of recollection and I read that Mark Twain had written solely about his daughter for a year following her early death. So I began to keep small, pocket-sized notebooks. I enjoyed going in search of them and attaching pens. I relished finishing them off. I felt the reward of accomplishment. A friend said that writing is a muscle that can be exercised, that writing becomes easier and better with practice. I like the idea of writing as practice. I didn’t share those notebooks. They remain in a box, never read after they were completed. But the practice became my way of life, my response.

In a way, Najeeb has become a wraith in the fiction I write. Because in the fiction, he can approach. I can work with feelings that I might otherwise have to avoid or would not have experienced. In the fiction, I can plan and construct a life and enjoy all of my feelings of parenting, creating a better version of myself and showing it off.

Najeeb. Fifteen.

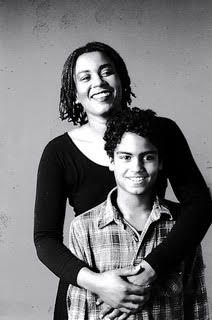

“Breena and Najeeb in an embrace of flannel that smells slightly of boy sweat and the aroma of his hair and the warmth of his skin and the feel of his heart beating through the shirt. If only.”

Breena Clarke is the author three novels, most recently completed, Angels Make Their Hope Here, set in an imagined mixed-race community in New Jersey. Her debut novel, River, Cross My Heart was an Oprah Book Club selection. Her second novel, Stand The Storm, is set in mid-19th century Washington, D.C. She is on the board of A Room Of Her Own Foundation, is co-organizer of The Hobart Festival of Women Writers and on the fiction faculty of The Stonecoast MFA in Creative Writing at The University of Southern Maine.

Breena Clarke is the author three novels, most recently completed, Angels Make Their Hope Here, set in an imagined mixed-race community in New Jersey. Her debut novel, River, Cross My Heart was an Oprah Book Club selection. Her second novel, Stand The Storm, is set in mid-19th century Washington, D.C. She is on the board of A Room Of Her Own Foundation, is co-organizer of The Hobart Festival of Women Writers and on the fiction faculty of The Stonecoast MFA in Creative Writing at The University of Southern Maine.