Review by Melissa Ridley Elmes

Review by Melissa Ridley Elmes

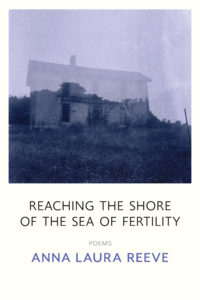

No poet is an overnight success. While Anna Laura Reeve’s first collection, Reaching the Shore of the Sea of Tranquility was published by Belle Pointe Press earlier this year, with many of its poems finding their way into the pages of literary journals throughout 2021-23 to great acclaim, including winning the Beloit Journal’s Adrienne Rich Award and garnering two Pushcart nominations, her first poem was published in 2011. The silence of nearly a decade between that first poem and those comprising this collection should not be understood as empty. One of the great mistakes people who do not hail from rural areas make is to believe it is peaceful and quiet away from the hustle bustle and noise of the urban landscape. Nothing could be further from the truth, and, as Reeve makes clear throughout this collection, she has all this time been listening to, translating, and distilling the loud of Southern Appalachia’s flora, fauna, and community into these poems. Equal parts musicality and primal scream, birdsong and baby crying, colorful plants and drab household, this book probes deeply the landscape and soundscape of the region in which the poet grapples with birth and depression, being an artist and being a mother, and the wonders and vulgarities of being. The difference between her earlier poems and these lies primarily in the unflinching honesty, gritty realism, and evocative imagism with which Reeve brings her postnatal world and life into focus for her readers.

In 42 poems–perhaps coincidentally, perhaps not, given the subject matter, the answer to the Universe–contained within five sections, like a classical play structure, Reeve carries us from the early days of an overwhelmed mother of a premature newborn through that child’s toddlerhood. The first section focuses nearly exclusively on the infant and mother, the world closed-in on this essential relationship, the concern to preserve the life that has come at such cost, the mother noting but unable to respond to the sour smells and untidiness of an apartment she can barely keep up with as she struggles to find balance. In parts two and three, the infant’s newborn status fading and the mother becoming more assured of her ability to nurture the child, the mother dares to look out again into the wider world, seeing, imagining, and revisiting familiar sights and sounds of the Smoky Mountains with keener observation and a desire for relationship with the environment in which she and her child are now being raised together. Those who have been parents themselves will recognize here that supermom charge of energy and optimism: I’ve got this! I can do it all!

Part four returns to a primary focus on the human, the mother realizing the limitations of a life lived with children, as well as its beauty, finding herself constrained from fully becoming what she has hoped–a mother-artist, a poet-parent–communicating with other parents and comparing herself to other writing women with alternating frustration (“Come / down here, the water is fucked”) and self-deprecating humor:

Eavan Boland wrote in her home study

While her children played elsewhere in the house

So it must be possible, and therefore

I’m going to begin a zenlike

Practice of writing while my kid

Sings and drops things and

Tells me to come look at this.

Every woman seeking a creative life in the midst of parenthood will recognize the emotions behind this seemingly good-natured jab at the serene Eavan Boland, who, Reeve notes, was probably not really all that serene (“I see only a river moving through her pale eyes.”)

Part five grapples with the enormity of motherhood, wrestles with ambivalence concerning the possibility of another child, and finally comes to some level of acceptance that she is of and with this world as much as a result of her experiences with motherhood as not, that she can handle whatever comes, if she does so with an open heart and mind, gifts from her child’s experience of this same world:

… Here

Is my tired and beautiful skin,

My body full of knowledge,

On a ridge overlooking the spine of an ancient range.

Yonder are my mountains–unshorn, wise, free …

I who became a mother and left this world hold its invitation

In my body.

Let me remember myself

when I come into my daughter’s kingdom.

No overnight success of a poet could have accomplished what Reeve does here; a book about becoming requires time to become a book worth reading. Readers will be glad Reeve took that time.

Melissa Ridley Elmes is a Virginia native married to an Appalachian man, currently living in Missouri in an apartment that delightfully approximates a hobbit hole. Her poetry and fiction have appeared in Black Fox, Poetry South, DarkWinter, Ignatian Literary Review, and various other print and web venues. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Dwarf Star and Rhysling awards, and her poetry collection Arthurian Things was nominated for the 2022 Elgin award.