Review by Michelle Panik

Review by Michelle Panik

The book jacket for Dallas Woodburn’s collection of short stories, How to Make Paper When the World is Ending, describes itself as “the ghosts of what might yet be and the ghosts of what might have been,” which was intriguing enough to pique my interest. When the blurb subsequently posed the question, “How is each of us shaped by what haunts us?” I knew I had to read this book. While so many collections are organized around a subject matter, a setting, or a character, it’s rare that one operates within such an elliptical theme as the aftereffects of loss.

Many of the stories start out simply, but they aren’t simplistic. In the titular story, a woman teaches children how to make recycled paper at an outreach event for a trash transfer station. While environmentalism is woven into the story, it’s done so obliquely and without lecturing. Instead, the story remains the woman’s and, when her ex-boyfriend shows up, she is doubly tasked with recycling old into new—physically with trash and emotionally with her past relationship.

“Feeding Lucifer” is a coming-of-age story that explores the loss that follows a move. New to Southern California, the narrator agrees to care for a new friend’s pet rat and snake. At one point, she remarks, “Come on in, future, I thought. My life has plenty of room.” But this optimism is ultimately cut down and, in this way, the story explores changing friendships, young love, religion, hope, and, ultimately, disappointment.

Several stories include playful elements that make you laugh, and then pause, as character grapples with lost love. In “Receiptless,” a man attempts to make an in-store return of his ex-girlfriend’s heart. Through his interactions with a sales associate, which are both comical and sad, readers mourn his own broken heart and cheer for new love, all the while knowing he’ll probably be back at that counter soon. “The Man Who Lives in My Shower” begins as an absurdist tale of a woman who finds a man living in her apartment’s shower and soon dissolves into sadness as the narrator recounts the death of her fiancé.

The tone of “How to Make Spinach-artichoke Lasagna Three Weeks After Your Best Friend’s Funeral” is more methodical than playful, but clearly Woodburn was still having fun constructing a story around a recipe. Told in second-person, the narrator intersperses memories of a recently deceased friend while giving herself instruction on cooking a new dish. The directions, which aren’t typical of a standard recipe, reveal the narrator’s personality and mindset. Step number seven reads, “Mix until your arm aches.” And then, “Now for layering. Use those no-boil lasagna noodles; seriously, they turn out fine.” Because of how this story plays with voice, utilizes a unique storytelling frame, and slowly reveals a character’s personal loss, I found it to be the collection’s strongest story.

If the goal of literature is to examine a lived experience, then the stories in How to Make Paper When the World is Ending shed light on the basic human instinct of seeking solace. Although these characters aren’t comfortable in their own lives, it’s comforting to listen to their stories as they shoulder burdens of what is no longer there, and yet which still hangs so heavily.

Dallas Woodburn’s debut novel, The Best Week That Never Happened, was the grand prize winner of the Dante Rossetti Book Award for young adult fiction. She is also the author of the novel Thanks, Carissa, For Ruining My Life and the linked-story collection Woman, Running Late, in a Dress. A former John Steinbeck Fellow in creative writing, her work has been honored with the Cypress & Pine Short Fiction Award, the international Glass Woman Prize, and four Pushcart Prize nominations. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband and daughter.

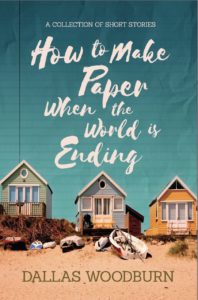

How to Make Paper When the World is Ending by Dallas Woodburn

Koehler Books, 2022, $16.95 [Paper]

9781646637034

Michelle Panik is a writer and elementary school substitute teacher who lives on the edge of California, in Carlsbad, with her husband and their two kids.