Review by Jennifer Martelli

Review by Jennifer Martelli

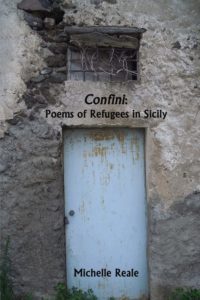

In the acrostic poem that introduces Michelle Reale’s latest collection, Confini: Poems of Refugees in Sicily, Professor Alex Otieno writes, “Liminal experiences of: working, loving, hoping, regaling, dancing and singing, summoning.” These poems, written in the voices of refuges from Africa, as well as the voice of the witness, occupy this “liminal space,” a space of confini: borders. Reale unflinchingly examines the borderlands of language, of confinement of the body, and finally, the poetry that witnesses the refugee who flees war, poverty, and environmental disasters that cause “any one of us to leave our home with the clothes on our backs.”

Throughout the book, Reale makes use of footnotes for the translations of words from Sicilian to English. As she states, “Words go subterranean,” and we, as readers, must look up and down the page for meaning. The act of understanding becomes physical. This underscores the sense of helplessness for the refugee, in a land with an alien tongue. Language can become weaponized. The poem, “Ab Ovo,” which translates to “from the very beginning,” ends with a menacing whisper, “in the language of the oppressor: pedronami.” These are poems with footnotes that become poems when you read down the page, beneath the word. In “Suleiman,” the footnotes read:

[1] Hospitality

[2] Integration

[3] Police

[4] Move

[5] Brother

Reale blurs the lines of physicality as well. Solid objects grow porous for the refugees, untrustworthy as “a country that hates him and that he hates back.” In “Chi Sono? (Who am I),” the speaker “knows of cardboard houses, fragile as a house of cards.” In one of the more heartbreaking poems, “Tibia Plays in the Refugee Camp,” the child

likes to play mommy. But first,

she colors the pictures she has drawn.

A small boat on a big sea, surrounded

by curly, cartoon waves. The waves

have eyes—thick angry eyebrows.

The landscape, too, becomes monstrous. In “Passage,” Reale writes,

Trees, sun, sand home skeleton key,

and village elders will be soon replaced with cement, salt water,

and indifference. This is not sweat. Those are tears.

In “The Half-Life of Boats,” the rust on these vessels used to make the deadly crossing “is alive.”

Reale balances the metaphorical dissolving of boundaries with the physical act of crossing borders. In these poems, she also confronts the idea of poetry of witness. In “Musa,” the speaker insists

This is my story. Let me unfurl it the way I want to. I am a

proud Susu from Guinea but the Italian people have fueled my

great, great delusion. Do not even talk to me of hopes and dreams.

The poems, “Nessuna Stato (No State),” and “Senzatetto (Homeless),” with their bilingual titles and written in the voices of the refugees, re-enforce the conflict between the refugee and the witness. These are poems that seek to express the humanity (or inhumanity) of these refugee camps. “. . .I am proud, but still I have no status. I am nothing and going nowhere,” and “I have no home” convey the more than just a liminal space, but a purgatory. In her brilliant poem, “Sgradito (Unwelcome),” Reale recounts a seismic moment when she, as witness, is expelled from the room,

I am so sick of you white people with our notebooks and microphones! Who do you think you are? You come to my place of business where I work hard, where I make my money and you want me to tell a fairy tale or a story of hard luck.

Get out! He yells.

My feet stick to the floor.

Sgradito! Sgradito! Sgradito!

How does it feel?

The poems in Michelle Reale’s Confini: Poems of Refugees in Sicily are dizzying in their poetic mastery and their brutal witnessing of the refugee crisis in Sicily. In her Coda, Reale tells us that “writing these poems and being among these men and women refugees . . . . helped me to see below the surface of things.” This is an essential book, not only for our fraught times, but for all time: a book of language, poetry, and dignity, written by an ancestor of immigrants. This is a necessary collection, where the poet will “catalog what we see, scratch details onto official reports. The shine of the eye, the crusted salt on parched lips, the blister of skin, the ball of fists.”

Confini: Poems of Refugees in Sicily

Michelle Reale

Ćervená Barva Press, 2021, 18.00

978-1-950063-25-3

Jennifer Martelli (she, her, hers) is the author of The Queen of Queens (Bordighera Press, 2022) and My Tarantella (Bordighera Press), awarded an Honorable Mention from the Italian-American Studies Association, selected as a 2019 “Must Read” by the Massachusetts Center for the Book, and named as a finalist for the Housatonic Book Award. She is also the author of the chapbooks In the Year of Ferraro (Nixes Mate Press) and After Bird, winner of the Grey Book Press open reading, 2016. Her work will appear or has appeared in The Academy of American Poets Poem a Day, The Tahoma Literary Review, Thrush, Cream City Review, Verse Daily, Iron Horse Review(winner, Photo Finish contest), and Poetry. Jennifer Martelli has twice received grants from the Massachusetts Cultural Council for her poetry. She is co-poetry editor for Mom Egg Review and co-curates the Italian-American Writers Series. Jennifer Martelli received degrees from Boston University and the Warren Wilson M.F.A. Program for Writers.