Review by Sunni Brown Wilkinson

Review by Sunni Brown Wilkinson

If one virtue of poetry is to give voice to the too-often voiceless, then Jessica Cuello’s collection Liar sings: for the forgotten child, hungry child at the back of the classroom, girl in a world without touch, girl who’s called a “whore,” girl tripping behind her mother at the laundromat, child in the hospital bed, the silent, the illiterate, the fatherless, the motherless. Liar sings the blues of the ignored, the unwanted, the untouched. And like song, the constraint of the voice, the pitch of individual witness, the tenderness for the world in spite of pain, comes through. These blues are a collection of what we fear and ignore in American society, the antithesis of the American Dream.

Liar is ripe with poems of house fires, neglect, hunger, abuse, sickness, and suicide. Shame is a flag nearly every poem raises, and the collection as a whole casts a light into the fissures of the archetypal nurturing family. There’s a terrifying distance between family members: absent father, absent brother, mother who is afraid of touch.

From “Flesh”:

At my wedding she doesn’t touch me We hold a little scalpel of hate

against our skin Flesh of our flesh Who can say where I begin

Sometimes she puts a photo of a cousin on the fridge to say I love this one

that is not you

But laced throughout are the mercy and gentleness of strangers: an adopted grandma who finally offers love, forgets she isn’t blood, is proud of the girl’s singing, forgives the girl for burning down her bathroom; a librarian who is Love; a gentle babysitter eventually sent to an insane asylum, who takes photos of the child, buys her an Easter basket, wears her black hair down, “a child could admire it.”

Cuello writes regularly from the perspective of the child. Often that means using the first person, but other poems employ a more remote third-person voice that magnifies the strangeness and otherness of identity. The child becomes an “it,” an object observed from a distance, as if this splitting of the self allows the speaker to process existence.

Cuello’s unique choice to adopt the spelling sensibilities of a child also deepen the authenticity of the voice. The titles of several poems reflect this: “Hungur,” “Stumic,” “Liyer,” “Chiald at the Library,” “Imona” (Pneumonia), “Solgire.”

“Hungur”

Grown-ups made a body. Made it

like a weed and sent it to school.

The bones grew. The skin stretched.

The body sat in the square of the desk.

Hungur pulled. The alphabet lined

the board. The words That This Those

were tacked to the wall, strange suns

the head grew toward.

The child is not yet a whole entity, a fully-realized person, but a shape, and “the head” appears as a kind of warped sunflower on a spindly body that craves light and food. Language, like the alphabet, is that light and food. The child develops language slowly and haltingly at times, becomes voracious and biting at others, and in this, language is both dangerous and liberating. But for the “chiald,” language is also the only currency she has to buy a place in the world. She has to spend it carefully. As a child of trauma and shame, the words are stopped, dammed up in a body that’s trying to survive.

In “Liyer”:

I am the child of liyers.

The lady writes

Self-selective mute

down on her paper.

Grandmother says

We don’t know where

her words are

Staccato sentences and jolting, quick pivots characterize several poems and magnify the stark, startling honesty and observations of a child, looking and looking when the adults are busy in their grown up world. And the speakers of the poems do find moments of refuge. Once again, it’s language that saves, that is holy, a world higher than the constrictions of the Catholic school, the world of adults, strangling and strange.

From “Chiald at the Library”:

Chiald thinks

the librarian is Love.

Chiald wants to know

why chiald lives

what sacred is.

Sacred is the library.

Sacred are words

gathered into spines.

This collection moves beyond the gospel of childhood trauma. There’s no whiff of resilience, just honest survival. Dorianne Laux, judge for the Barrow Street Book Prize, called Liar “a highly original vision,” and the book as a whole shapes a singular witness of longing and individual grace. How can the body witness? How can the voice be heard? As Cuello writes toward the end of the book: Uncross… Let your chest see.

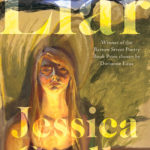

Liar by Jessica Cuello

Barrow Street Press, $18

ISBN: 9781736607534

Sunni Brown Wilkinson’s recent poetry can be found in Western Humanities Review, New Ohio Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, South Dakota Review. She is the author of The Marriage of the Moon and the Field (Black Lawrence Press) and The Ache & The Wing (winner of the 2020 Sundress Chapbook contest). She also won New Ohio Review’s NORward Poetry Prize and the 2020 Joy Harjo Prize from Cutthroat: A Journal of the Arts.