Review by Celia Jeffries

Review by Celia Jeffries

It’s always a pleasure when a poet turns to prose—language is bound to surprise and sparkle when a such a writer distills thoughts onto the page—and that is exactly what happens in Elaine Terranova’s memoir The Diamond Cutter’s Daughter. “My name is Esther. It isn’t, though it was meant to be.” (3) The opening line pulls us into a conundrum, into the prism of Terranova’s world. Esther was the adored cousin who died before the narrator “was floundering around in my mother’s belly, finally ‘tearing her open,’ as she liked to describe it, waiting for a name.” (5) “I was referred to simply as the Baby in our house, and on our street, generically as “the diamond cutter’s daughter.” (5)

The story moves forward in short one, two, and sometimes five-page vignettes, as the narrator finds herself in a world where “there just wasn’t that much love to go around.” (6) She enters the world during the Depression, the youngest child of an Orthodox Jewish family trying to survive the aftermath of the Holocaust, to a father barely making a living working to refine precious stones for the wealthy, and a mother hobbled by the arrival of a late-in-life child. The only daughter, she is years younger than two older brothers, and searches the house for reading material, looking to satisfy a passion of her own. This is a perspicacious child: “Early on, by the time I am four maybe and able to look past myself, I know intuitively that each member of my family is living in a trance.” (31) Already, the poet is at work, looking at the world from all sides, trying to understand what she is seeing.

The family’s prospects improve as men return from the war and need diamonds for their brides. Terranova begins moving back and forth in time to tell the story of her brothers, one of whom goes into the family business, the other who, like her, gets a college education and who she visits in his nursing home: “We borrow him from his dementia to which he will just as cheerfully return in a couple of hours. . .so glad to see me, the last remaining member beside himself of his first family, the person in the world most like him.” (102)

Terranova’s story is a beautiful rendering of a world now past—row house culture in Philadelphia where a mother will walk blocks to trade with the right butcher or the best milkman, and where neighbors watch each other day and night both to keep everyone safe and to keep everyone in line. But Terranova captures much more than that. Family, she writes, is “like Atlantis, a continent that cannot be recovered but just resurfaces in the fragments of memory.” (166)

In a passage titled “Flaws, Faults” she pays tribute to the connection between her work and her father’s. “So if a diamond is the hardest natural substance while graphite is among the most malleable, it was a little like my father and me. Both are forms of the carbon atom, in the same family, so to speak. A diamond is transparent, a pencil mark, opaque. I think how a pencil is my writing instrument of choice though because it can be erased. You can change your mind. It streaks along the paper, plant on plant. A diamond, they say, lasts forever, but so too, I’d wanted to tell him does some writing.” (72) And so too, should this sparkling, many-faceted memoir.

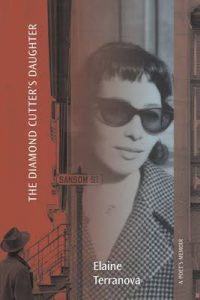

The Diamond Cutter’s Daughter by Elaine Terranova

Ragged Sky Press, 2021, $18 paperback

ISBN 978-1-933974-41-5

Celia Jeffries is a writer, editor, and teacher whose work has appeared in numerous newspapers and literary magazines and has taken her from North America to Africa, and many places in between. Blue Desert, her first novel, was published this year.