Reviewed by Suzanne Edison

Reviewed by Suzanne Edison

Jessica Gigot is a farmer, poet, teacher, and musician. She is the author of Flood Patterns, (Antrim House Books, 2015), and her writing appears in such publications as Orion, Taproot and Poetry Northwest. She teaches poetry workshops and eco-poetics through Richard Hugo House in Seattle, WA and on her farm, Harmony Fields, in Bow, WA. Additionally, she writes about food, sustainable farming practices, and is featured in a TedX Talk, The Poetics of Food, 2017.

I met Jessica as a fellow student in a poetry workshop during this pandemic year, via Zoom. Though we live about an hour from each other, we’d never met. In this workshop, as in her newest collection, Feeding Hour, I was struck by her quiet and profound understanding and insights into the relationships between husbanding—from hús ‘house’ + bóndi ‘occupier and tiller of the soil’—and mothering of animals, land, and humans. Feeding Hour is a closely observed book of descriptive poems on these intersections. Mark Doty says in The Art of Description: Word into Word that “description is fueled by HUNGER for the world, the need to taste, to name, to claim what’s seen…Language is hungry…it wants, as it were, to eat everything.” Gigot is hungry to tell us about all she observes and experiences as a shepherdess, land steward, and mother. These poems locate us in her landscape, we inhabit them and learn the habits of the flora, fauna, and people around her.

The central theme for this book (dedicated to two of her ewes, Bertha and Ruth, from whom she learns important lessons) emanates from the poem, “Year of the Sheep” (12). Gigot says here, “The work is simple: nurture. // Let your little flock teach you / All you need to know about love.”

Gigot not only tends flocks of sheep but is also learning how to carry, birth, and raise two children of her own. The sections of the book reflect these themes: “birth stories”, “digging”, “familial truths”, and “mothering”. In section I, four poems have the same title and are numbered 1- 4. In “birth story II” (9) she says,

This ewe does not need my help

but I need her to teach me

all she knows about animal

bodies and miracles, mothering

and being mothered.

Throughout, Gigot strives for quiet and patience. In the ekphrastic poem “Moments of Pause” (12) based on Jean-Francois Millet’s “Shepherdess with Her Flock”, she says:

I crave moments like these

When peace and harmony

Seem inevitable.

and, “I strive for her contentedness / Though I know it is fleeting…”

She comes to see how pain is also a teacher in the poem “The Story of Ruth” (15). Ruth is a ewe she has raised by bottle, presumably because she was neglected or rejected by her mother, and who is now ill. Knowing she must separate Ruth from the others she remembers,

that life spawns more life

and what we care for comes

back to us in hard

and mysterious ways.

Gigot most often uses everyday language; she is more Germanic than Latinate. Words like flock, walk, touch, grow, roar, belly, farm, land, roots, and pray, crop up frequently. But ruminant, rhizome, and liminal also populate these poems creating music in their tensions. In “Digging Up Irises” (21) Gigot’s neighbors are noisy as she transplants iris corms.

I made new spaces

for these tired roots.

I did not complain about the noise.

I kept digging and planting

remembering that the veil

of separation is thin

and life like a rhizome

is resilient and always connected.

Section II, “digging”, unearths poems about human relationships, climate change, and expands the animal world to include species that live near, or migrate to, her home in the Skagit River Valley, which is a major flyway stop for trumpeter swans, snow geese by the thousands, pelicans, and legions of eagles. In “Two Mothers Walking” (23) the pelicans are out of place, too far north, “but what is normal anymore?” Indeed.

By the book’s end, we are sated; we feel the accumulation of seasons, cycles, new life, loss, and appreciate the transformations of the poet / mother / farmer in herself. In “Carry-On” (67), the speaker boards a plane but she feels too light, as if missing something. It is her first time leaving her child. She touches her belly, feels the ache in her breasts and understands a central contradiction of love and mothering: “I must go, I must never leave you.”

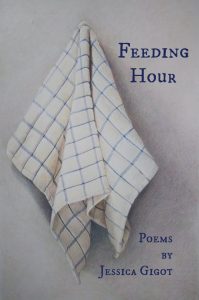

Feeding Hour by Jessica Gigot

Trail to Table Press, an imprint of Wandering Aengus Press, $18, paper

ISBN: 9780578714615

Suzanne Edison, MA, MFA. Her 2018 chapbook is The Body Lives Its Undoing. Other poems are found in: Michigan Quarterly Review; The Naugatuck River Review; Scoundrel Time; Mom Egg Review; Persimmon Tree; JAMA; SWWIM; and elsewhere. She is a 2019 Hedgebrook alumna.