Review by Anne Britting Oleson

Review by Anne Britting Oleson

Donald Rumsfeld famously said that we don’t know what we don’t know.

In her literary memoir run scream unbury save, Katherine McCord makes this very clear, and this engenders a certain anxiety in her audience. The book is constructed as a series of prose poems, sometimes with innocuous titles like “SHELVES” or “CAMPING”; sometimes one of those titles is drawn from the content of the piece on the preceding page. Sometimes, though, not: as in “ADDENDUM/APOLOGIA/ERRAT(A OR UM) AND ADJUNCT/ADJUNCT PROFESSOR (LATER THAT (THE PREVIOUSLY NOTED) DAY). What is going on here? Or, to mimic McCord, WHAT IS GOING ON HERE? It’s obvious she wants her audience to be asking that question, over and over, while reading: at one point, she titles a piece “CLUES,” but what exactly are these clues hinting at? Is everything in her life, in her memoir, a clue? Or is nothing?

McCord is playing games with her readers, while at the same time she’s being deadly serious. Prose poems, by nature of their construction, deliver more language than verse; but rather than hand the reader more explanation, McCord uses the form and the language to deliver more obfuscation. Here, she seems to be saying, let me tell you something vital. Yet there are details missing—though readers might not realize that straight away. She writes, early on,

(There may be some cross-referencing in this book. Okay, there is. But it will fall off. And sometimes I’ll later contradict what I’ve said. But all in good fun). (ix)

She passes out information with one hand, and then takes it back with the other. Or perhaps piles so much of it up that the reader is buried and cannot be sure what is real and what is sleight of hand. She freely admits to it all, though at times with a Dickens-like slant, as in “SHELVES”:

Piles are the key to life. Drawers should be mostly empty. If it’s in a drawer, take it out and examine it. Think of what it would be good for, clean it, organize it in terms of its parts—make sure they work, or maybe not—and then zen-like, place it in a random space, on top of a pile in a basket, on top of a pile on the dining room table, on top of a pile near the kitchen sink, on top of a pile on the toaster, on top of a pile on any flat surface. (9)

So many piles of things, so many piles of information: so much that readers are lulled into thinking we see everything, and know everything, when upon consideration, it’s obvious we do not.

This is not in any way accidental. McCord’s subject matter in this memoir is the effects of growing up in a CIA family—the alcoholic father serving in posts in Africa, the young frightened mother of two (three? four?) children keeping a gun under her pillow at night, and finally suffering a nervous breakdown that precipitates a quick government-sponsored removal stateside. In the present of this memoir, there is no evidence of the father; he only appears in the past. Why? Is he dead? How? The mother makes appearances in both past and present, as does the speaker’s older sister…and there are brothers, mentions of whom are so scarce that they surprise. Wait, there are/were brothers in this family? This is a family of secrets, some that the speaker has known all along, some she is just discovering, some about which she does not seem to know. In an untitled piece which might or might not be part of the preface (the structure of the entire book feels at times fluid), McCord writes

Promises, promises. Welcome to my world, part one. Actually, no one promised me anything. It’s sorta been the other extreme. I’ve gone after anything that can promise me nothing. Such makes more sense to me. (xii)

The shifting sands of the knowledge of her own life are spread beneath the reader’s feet as well: McCord is playing with our reality as fate has been playing with hers. We think we know what’s going on? We have no idea what we don’t know. And this keeps readers looking over their shoulders—long after closing the book.

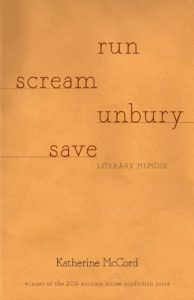

run scream unbury save

by Katherine McCord

Autumn House Press, 2017, $17.85 [paper]

ISBN: 9781938769184

143 pp

Anne Britting Oleson is a writer from Central Maine. Her poems have been published in literary magazines world-wide. She is the author of two chapbooks, The Church of St. Materiana (2007) and The Beauty of It (2010), and two novels, The Book of the Mandolin Player (2016) and Dovecote (forthcoming 9/17).