Reviewed by Judy Swann

Reviewed by Judy Swann

When my friend tells me this loss

will open the way

to all the others in my life

I think of the way I am drawn (86)

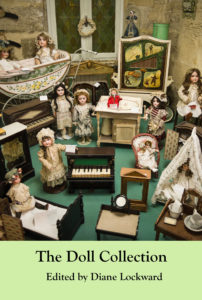

So says Wisconsin poet Andrea Potos in “Every Body She Carries,” one of the eighty-eight poems in Diane Lockward’s uncanny anthology The Doll Collection. How do we become who we are, how are we drawn? For little girls, dolls have been an integral part of becoming. My grandmother used to call me her “Dresden doll,” after all, and sometimes I still am.

Much of this volume is devoted to antiques, collectibles, or memories of youth. Please don’t miss out on Frozen Charlotte! But there is no celebration here of the Sims, no Pokémon, no Bratz, no Ikuzis, nothing time has not softened. There are Barbies, Raggedy Anns, matryoshka dolls, Ginny dolls, and Chatty Cathies, whose Christian name (as we used to say) peaked in the U.S. at about 1950, a name almost never nowadays bestowed; there are the iconic American Girls. There is rare, surprisingly oblique engagement with the questions of female agency and the racialized stratification of identities, cerebral material that the sociological literature on dolls—and fashion modeling—is replete with. Do girls and women become who we are by filiation and descent alone or is there a force other than time, something innate and irrational, that shapes the chaos of who we are into the differentiated individuals we become? I believe that our desires are responsible for much of who we are: I believe love shapes us. And have we not all loved our dolls?

More than one writer addresses the curious phenomenon of the doll house. They didn’t make houses for G.I. Joe! Meditating on silent film star Colleen Moore’s doll house in Chicago, poet Susan Elbe writes:

I yearned, not for the priceless objects,

But for the perfect life

I was certain burned inside that house. (39)

Moore cycled through four husbands in her life time—how perfect is that? Moreover, her dollhouse includes a traditional talisman of women’s magical journey towards fulfillment, special shoes:

The smallest slippers ever made, one-quarter inch long

Crimson felt with hand-sewn leather shoes (38)

The Doll Collection poets are heavy hitters. They are prize-winners of all kinds, including the Pushcart, the NEA and Pew fellowships. They are Poet Laureates. They have published in Poetry, The New Yorker, Prairie Schooner, Rattle, and Verse Daily. Most are in the U.S., but not all. They teach at universities nearby you and they edit journals you read. Editor Diane Lockward’s deft curating for her own imprint, Terrapin Books, leaves the reader with only one regret: she included none of her own poetry.

One poem I particularly like (because it reminded me of my mother singing Bobby Shaftoe to me) is Carine Topal’s “Dresden China Boy”:

I take you down, dainty

globe-headed perfect you,

small monument of love

that I reach for,

you in the mirror,

dressed in your pout.

Oh, vacant baby in mid-gesture.

Oh, glass-eyed witness

in my dusty-rose room,

romantic roulette of my girlhood,

femme-eyed pretty boy,

my glazed baby-cake,

my Wolfgang,

my Friedrich.

Kiss me! (109)

How different in tone and intent from Topal’s nubility is this excerpt from Ann Fisher-Wirth’s “Snake Ladies”:

Then rising from the bathtub we wrapped ourselves in towels and began to dance the Dance of the Snake Ladies in that steamy, shadowy room, clutching our towels but weaving our hips in the nine-year-old version of sinuous circles, jerking our heads from side to side, oh we were transfixed by what we thought was evil, and slithering into the hall, into my little sister’s bedroom, where she was playing jacks with my Snake Lady partner’s little sister, we coaxed them into our dance. (45)

At the end of the poem, fecund, the snake ladies all choose a doll to nurse. This is the kind of poem that makes you turn off the room lights because the dark just feels right.

There are more themes in this anthology than I can possibly do justice to in a short review—abortion, fathers, doll-makers, paper dolls, doll hospitals, the Dionne quints; and there are forms galore—sonnets, a ghazal, a sestina. Each selection is a masterpiece, and each—in its way—vivifies for us what Marjorie Tesser in “American Girl” calls the “glut of love”:

Beside them is the mother,

her bob, too, is the color of the hair

of the doll with which she has endowed

her daughter, in glut of love, delivering

another like her, so daughter can,

like mother, love her

and thereby know herself beloved; (106)

From ordinary woman to goddess to doll—this book has it all.

The Doll Collection

edited by Diane Lockward

Terrapin Books, 2016, $18.99 (paper)

ISBN 9780996987103

Judy Swann is a poet, essayist, editor, and bicycle commuter, whose work has been published in many venues both in print and online, including recently, Writing In A Woman’s Voice, Mom Egg Review, and The Way to My Heart: An Anthology of Food-Related Romance. She blogs at ebikeithaca.org. Her book, We Are All Well: The Letters of Nora Hall, has given her great joy. She is currently riffing on a cartoon superhero from the 1980s in a soon-to-published volume entitled Je Suis Stickman. She loves. She lives in Ithaca, NY.