Review by Marcene Gandolfo

Review by Marcene Gandolfo

– In Sunday school, when we chose roles for the Easter play, no one wanted to play Judas. Understandably so. Judas Iscariot was the traitor, the villain. Who would want to be Judas? Then we realized, if no one played Judas, there would be no play. Judas character – however despised – was an integral part of our story. Without Judas kiss, there would be no Easter. I began to feel sympathy for this man, who was left in the end, hanging from a tree, detested for centuries. Years later, my interest resurfaced when I read the gnostic Gospel of Judas, which suggests that Jesus asks Judas to betray him. From this perspective, Judas’ maligned kiss is an act of obedience. This raises the question: May an act of obedience simultaneously be an act of betrayal? It also asks: Is Judas the one who has been most profoundly betrayed as he as been vilified throughout history?

In Becoming Judas, Nicelle Davis’ poems compel us to explore that crooked line that exists between obedience and betrayal. Early in the collection, the speaker refers to her strict Mormon upbringing and her departure from it. She recalls images from her childhood.

My myths crossed when I was four. I mistook a pastel picture of Jesus hung in very Mormon home for John Lennon. Both called the Prince of Peace. Was encouraged to talk to him. Offer up suffering . . . I still talk to John when praying to Jesus.

In many of her poems, Davis is asking: How do we live in a world of “crossed myths”? Do we maintain obedience to one and discount the other? Or do we gather images from different myths in order to weave a new tapestry, compose a mythology of our own. In these poems, Davis is engaged in crossing, weaving, linking images from religious mythology to those in popular culture, domestic life, even women’s clothing. Many of Davis’ “crossings” are quirky, strange, unexpected. But in those quirky juxtapositions, in that element of surprise, the poems gain energy and power. As we read Davis’ poems, we find that in these “crossings,” we make unexpected connections.

Several poems continue to play on the John Lennon / Jesus Christ association as Davis compares the worship of the material with that of the metaphysical. One of the most memorable of these poems, “Flash: Leibovitzs’ Photo of John and Yoko,” is an ekphrastic meditation on the famous photograph that graced the cover of The Rolling Stone. As Davis muses on this photograph, taken only hours before Lennon’s murder, she depicts a modern-day pieta, ominously foreshadowing Lennon’s untimely death,“ the sight of a man becoming a shrine.”

Other poems focus on the childhood images surrounding the speaker’s familial life. Again, playing on a conflux of obedience and betrayal, these poems speak to the ambivalence and complexities of family relationships. In “Enough Time,” the speaker recounts a childhood affection for her grandmother, but also a mischievous defiance:

I am seven. She is making me a black velvet dress . . .

at Christmas dinner, when

the conversation is years away from me—I arch my back to break the dress seam—for the sound of tearing open—for the attention of coming apart. I think it will be funny. This is the only time I will see my grandmother cry . . .

A number of poems link Mormonism with family life and ritual. In “Unlikely Origins and the Book of Mormon,” Davis imagines the private life of Joseph Smith. She portrays a complex relationship between Smith and his wives in the ritual of a game.

Joseph had an odd sense of fun—playing checkers with his wives by candlelight, all confused as to whose turn it was to go against him.

But the most significant and revealing images that run through the book are those of Judas himself. These images, taken from the gnostic gospel, depict Judas as Jesus’s close friend. Here the ambivalence between obedience and betrayal resonate most strongly. One of the of the most powerful poems in the collection is the solemn portrait of Judas’ mother, “The Woman Who Cut Judas Down.” The poem begins with the recognition that Judas could be anyone, or everyone.

[She] had lost her son. This body strung

from a branch, could be anyone—

even hers . . .

This poem, which portrays the grieving mother cutting her dead son’s body from a tree, humanizes the Judas character. Again, we see Davis play on another nontraditional pieta, a picture that many, attached to the traditional concept of Judas, may not have envisioned. In a subsequent poem, “Becoming Judas,” Davis identifies Judas face in her own mirror reflection.

I wipe steam off a mirror after a hot shower.

Face solemn from lack of sleep—a reflection

of Judas—dark opposite to the light we worship.

I refasten the silver-cord to my neck.

We ask,

How can I love you, the way that I do—

without having myself to loathe?

As Davis considers her own departure from her childhood faith, she identifies with Judas. She also compels her reader to confront his or her own “inner-Judas.” Who hasn’t disappointed a loved one? Who hasn’t diverted obedience from a set of values or expectations? Yes. We are all Judas. The traitor. The betrayed. The human being in all his or her contradictions and complexities.

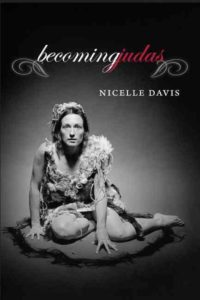

Becoming Judas by Nicelle Davis

Red Hen Press 2013