Review by Susan Michele Coronel

Review by Susan Michele Coronel

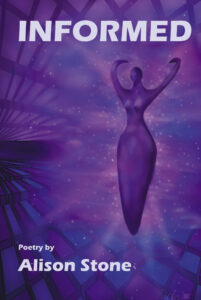

“What a woman knows, she tells slant,” Alison Stone writes in her ninth book of poems, Informed (New York Quarterly Books, 2024). In this stellar collection, Stone employs a variety of traditional forms through a strong feminist lens, addressing themes of loss, time and memory, the struggles of childhood, adolescence and dysfunctional family life, as well as sex, politics, pop culture, the lives of famous women, and the pandemic.

The book is divided into four sections. The first and last sections are devoted entirely to pantoums, the second to ghazals; the third is a combination of forms including villanelles, a haiku, an acrostic poem, a tanka about Stormy Daniels, and a crown sonnet about growing up in the 1970s called “Suburban Development.”

The pantoum and villanelle forms, which both utilize the repetition of lines, are perfect at evoking a haunting quality, and serve as reminders that the trauma of silence and indifference never leaves the female body. In “Choiceless Villanelle” Stone writes:

How fragile – heart, brain, womb, sinew, and bone.

How easily bodies, and dreams, can die.

A woman’s safest when she’s alone.

In “House” Stone asserts:

Girls learn disgust for their bodies,

heavy vessels of flesh that

open, clench. Hungry and alive until not.

You can’t stay safe there, can’t really leave.

The pantoums cover a wide range of territory, from adolescent experiences to the Biblical/mythical realm of Adam and Eve and Adonis, Louisa May Alcott (“How Louisa May Alcott is Similar to God”) and the murder of Heather Heyer during the Charlottesville protests (along with President Trump’s dog whistle “some very fine people”).

While reading numerous poems written in the same form, I was impressed how effortless they seemed. For those of us who dabble in form but seem intimidated by using it regularly, this collection is a primer in how to do it well while staying strikingly relevant. The material addressed is often difficult – a community’s silence about a childhood death, frequent adolescent bullying, sexual abuse, and rape.

The continuous use of form serves as a container for troubling emotions and experiences. Their cool exterior contrasts with the trauma of the material. In “Learning” Stone writes, “We saw (but never talked about)/ Mr. Jones’ look down girls’ shirts/ Jill got hit by a car and died./ What we didn’t say lodged in our bodies.”

In the formative years of the speaker’s life, trusted adults lie to themselves and their children, living in constant denial. In “Picket Fence” Stone writes: “The Mother drinks in secret./ The father punches his shame into a wall./ So many ways to pretend.” Also: “How did love end up like this,/ dinner finishing in tears/ as the TV blares fake mirth?”

In a hypocritical, confusing world, the speaker has no choice but to look within to find her own truths and transcendence, but finds the reality of the world crushing: “I sang loud and hungered with my whole heart,/ until I didn’t,” she writes in “Inspired by a Line from Janis,” “and days got stained with disappointment./ Other people’s needs a cloak of lead.”

For me the sonnet crown “Suburban Development” was one of the jewels in the collection. As Stone’s contemporary, I felt that she described the same emotionally unhealthy landscape in which I grew up. In fifteen well-crafted poems, the crown sequence chronicles how adults’ evasions and illusions, along with gender stereotypes and sexism, almost wrecked a girl who saw beyond them. “I starved myself to safety, transcendence,” Stone writes.

Television culture is no better:

The raped woman used to star in Bewitched.

People kept saying that it was her fault.

She couldn’t twitch her nose and make things change.

Each birthday I wished that magic was real.

Even well-meaning adults carry sexist perceptions damaging to girls and women who hear those views firsthand, and are afraid to speak up:

Dad said that someone’s looks shouldn’t matter,

but he talked about cute blondes and pointed

them out to my brother. When one walked by,

Mom’s lips got thinner and she looked

like she might say something but then didn’t.

There was always something not being said.

In an effort to maintain distance from these difficult emotions, the speaker employs a wry, dryly humorous tone. This creates an effective tension between events and their retelling. “Is that a crocus? Do I discern spring?” she writes in “Less Stern.” “Where does middle-age fancy turn in spring?’ In the villanelle “News,” Stone says:

Adam lost a rib, Van Gogh an ear.

Vodka puts a leash on fear.

Earth’s an ellipse, not a sphere.

What can cure, can ail.

There’s a dead mother in every fairy tale,

have you noticed? Poor Freud’s gone stale.

The mood is lightened a bit with pop culture references to the Rocky Horror Picture Show and musical artists such as Whitney Houston, Adam Ant, and the Nine Inch Nails.

There are a number of poems about the pandemic. Like most of us, Stone spent time in isolation, thinking about lost lives while encountering a troubling stillness. “What are the songbirds saying,/ loud outside my window as I grasp at sleep?” she writes in “Quarantine Morning.” “Trees pour shadows onto empty streets./ The air is sweet, clean of machines.” Political commentary cannot help but seep into the conversation about those dark days, as Stone references hate crimes against Asian-Americans:

There must be someone to blame.

School becomes the kitchen table.

Today’s lesson: fear. Tomorrow: death.

Throughout the book the speaker looks for ways to cope – lovers, poetry, burning herbs, bad advice – but the past continues to take its hold. In “House” she writes:

The past takes so much attention,

why has the spirit nowhere better to live?

What’s incomplete pursues us. Everywhere,

childhood’s house of slanted rooms.

Ultimately a combination of a life deeply lived and a strong lyrical voice comes shining through, offering both speaker and reader acceptance and wisdom. In “Lost Ghazal” Stone writes: “I want to die fully spent, each heart-stone / turned. Dissatisfaction, that culprit, lost.” In the last stanza of “April Ghazal” Stone says, “Let your life’s constraints melt off like snow. Speak/truth loudly, Alison.”

I came away from “Informed” not just informed, but illuminated and transformed.

Susan Michele Coronel lives in New York City. Her first full-length collection, “In the Needle, A Woman,” won the 2024 Donna Wolf Palacio Poetry Prize, and is forthcoming from Finishing Line Press this July. A two-time Pushcart nominee, Susan Michele Coronel has had poems published in numerous journals including Mom Egg Review, Redivider, One Art, TAB Journal, and Spillway 29. In 2023, she won the Massachusetts Poetry Festival’s First Poem Award. Versions of her book were finalists for the 42 Miles Press Poetry Award (2023), the C&R Press Poetry Award (2023), and the Louise Bogan Award (2024).