Seeing Our Children in Art: on “The Stone Boat” in Kelly McMasters’s The Leaving Season

Seeing Our Children in Art: on “The Stone Boat” in Kelly McMasters’s The Leaving Season

A Literary Reflection by Anna Rollins

Recently, I archived photos of my children’s faces from my public social media accounts. I’d always given thought to how I posted their images for anyone’s access. I made some rules (that I occasionally broke): only post older photos so that their immediate identities are not apparent. Try to mask their features with averted eyes or masks. I was not sure what influenced these guidelines. I was also uncertain of my motivation in making them. Did I fear an outside threat? Was this general respect for privacy? There would always be danger for anyone existing as a body in the world – but I didn’t want my desire to be seen to hurt my children.

My children, though, do appear in my writing. I’m not sure I would be a writer if not for them. Though some fear motherhood and its strictures as taking away from the time to create, for me, for many, motherhood led to the opposite. Yes – it contracted my world. But in so doing, it allowed me to see what was right in front of me. It narrowed my scope in a way that allowed me to finally focus.

Motherhood stripped away bits of freedom I did not know I possessed – the freedom to go for a walk whenever I pleased, to go to bed, to swing by the grocery store for a gallon of milk. On many days, the only place I could find a modicum of opportunity was on the blank page. And so, writing became a coping mechanism for the self-denial that is so much of motherhood.

Of course my children appear in my art.

But at what cost? That is the question Kelly McMasters takes up in her essay, “The Stone Boat,” from The Leaving Season. In this essay, she explores the role her children play in both her art (writing) and their father’s (painting). As co-parents, they both decided to leave their children’s photos off social media. They could not consent to the archival of their digital representations, after all. But the role their children’s representations would play in their art was a more nebulous concern.

A reader of McMasters’s memoir can see the care given to conceal her children’s identities in each chapter. The book – one about marriage, motherhood, and what remains when the spark of romance leads to a life in flames – certainly features her children as major characters. But they are shadowy figures, without names and often without physical description. We see one napping in a bookshop or playing chess after school. Occasionally, they speak. But they act in service to a larger personal narrative. They are, as characters, deliberately not fully developed. Should they grow up to become writers, their stories would remain unspoken, theirs to fully tell.

And this is deliberate on McMasters’s part. She refers to her writing about her children as “just a portrait, one of many. I tell myself that I’ve taken care to cover my children’s bodies here on these pages.”

The occasion for “The Stone Boat” is an instance when her former husband, denoted as R., did not take this same care. McMasters received a message from a friend: had she looked at her former husband’s Instagram account lately? She had not. And when she logged in, the images she saw made her run to the bathroom to retch. Though both had decided to not post photos of the children online, R. had chosen to post images of a portrait he’d painted of them: “there were multiple shots of the painting; different close-ups of their faces, their feet, a hip and a hand. One wide studio shot was all Instagram-perfect north light and golden barn beam, their little red bucket swing down in the corner, chain curled like a snake. In this photo, a canvas I guessed was about six feet across held their complete naked bodies. A swipe of grey and blue between their legs hung sadly against their thighs, each toe on each foot a tiny round pebble. Their sweet faces were rendered slack in R.’s awful hauntological hand.”

One of R.’s former subjects, a poet, described his work as “hauntological.” McMasters defines the term, not as a painting that appears haunted but one where the subject’s fate was written “into a certain future.” There was a certain, fated omniscience that hung heavy upon his subjects’ visages – and this quality was present in the portrait of their children.

Eventually, someone called Child Protective Services about the, arguably, pornographic artwork. But the situation was a unique one: typically, the medium under investigation would be photography or film. Not a painting.

McMasters, though horrified that R. shared the images of the painting online, still understood his artistic impulse: “part of me could understand his drive to make a painting of his children. No part of me could understand his making the painting he did, nor sharing it.”

And R. argued that, initially, the painting was private. His original intention was not to share the portrait with the public. But then, something overcame him. It wasn’t a lack of care for his children, their privacy or autonomy. It was a devotion to his art. “The painting was just so good,” he argued in his defense.

This line of reasoning is one familiar to any artist. I, too, have gone to the page to write a scene, private, for myself, telling stories I’d never dare share – and then I share them anyway. In sentences I labor over, constructing then reconstructing, even something true and intimate, eventually feels constructed. Nonfiction is still composed. Even when I’m working with material from real life, my art becomes a new creation.

And so, McMasters grapples with this question throughout her essay: what does it mean to make art as a parent? If your children are a chief part of your identity, how do you express that part of yourself without violating their privacy and autonomy?

She does, after all, describe the painting in this essay. She uses words, her own preferred medium. And though she takes care and discretion to narrate this essay about art and motherhood, boundaries and consent, she cannot escape the fact of her children’s bodies, though she often tries to transpose the shadow rather than the actual physical form.

When I hid the direct images of my children on my public social media page, I realized that there was hardly any personal photography left. Sure, there were some shots of birds in trees, a July sky’s sunset, but as far as images of myself? There were few. Online, it was hard for me to curate an identity apart from my children’s sweet faces. They were the better part of me. Their stories were deeply intertwined with my own. Though I take care to cover their bodies in my sharing, my art, I resonated with R.’s impulse, the temptation to violate my ideals because an image or a line is just too good.

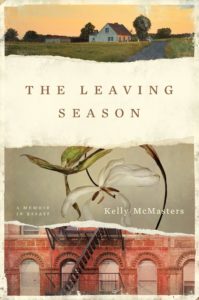

The Leaving Season by Kelly McMasters

W.W. Norton & Company, May 9, 2023

ISBN: 978-1-324-07605-6

Anna Rollins’s work has appeared in the New York Times, Slate, Salon, Electric Literature, Joyland Magazine, and other outlets. Her forthcoming memoir, Famished, (Eerdmans, 2025) challenges scripts that encourage women to take up less space and not trust their own bodies, messages that are common in diet and purity culture. She is a faculty member in the English department at Marshall University.