Review by Ellen Meeropol

Review by Ellen Meeropol

When the reader first meets Mia, she is trying to find her bra. “I live in my car,” she tells us, “and I only have one bra. It has to be around here somewhere. I don’t like to sleep with the bra on. It’s a little scratchy. For those of you who have never worn a bra, let me be honest, you aren’t missing much” (1).

Mia’s voice captivated me from her first words. A homeless young woman living in Los Angeles, we meet her in February 2020, just as the pandemic is about to disrupt her already shaky existence. She lives in her car, attends community college, and cleans the houses and watches the children of rich people as she saves money to attend UCLA. Mia is smart, savvy, thoughtful, and full of ideas and curiosity about the nature of the society that separates her and her friends from the wealthy people they work for. Her voice is the engine of this novel, which gathers speed and depth as the pandemic intensifies and the 2020 election approaches.

The Los Angeles setting is strong and visceral. “This is a city that eats you up and vomits you out,” Mia observes. “Look at all these homeless people. You can die in Los Angeles lying against the shining palm trees in Santa Monica. I help a lot of people; I am the one who helps people all the time. People call me for help. When my phone rings, someone wants help. No one saves the savior” (78).

I am not familiar with the neighborhoods Mia travels but Gale’s descriptions, lush and biting, bring them alive. There’s Topanga—“house full of crystals, and it had a fire pit in the middle, and a bunch of benches around it with blankets. I assumed she either had a lot of parties or it was for some kind of ceremony. She seemed like the ceremony type.” (3) There’s Calabasas and Bel Air and Bull Canyon and Mulholland Drive—“the house is six thousand square feet. We end up filling up three of the bedrooms with honey and peanut butter, many rolls of toilet paper and paper towels; he is ready for anything” (28).

The wealthy people of Calabasas and Bull Canyon who Mia works for are occasionally kind, even generous, but one employer makes the situation clear. “ ‘I own your ass,’ she says. ‘Don’t forget.’ “ (46). Several chapters give us the point of view of Mia’s employers, who think they know who Mia is. “I’ve never really asked, but I think her parents spoiled her and then she just decided that she wanted to make her own money” one woman tells her friend (12).

But Mia sets us straight; her mother joined a cult when Mia was a baby and divorced her father. After being presented to the cult leader when she was 14 for his sexual use, Mia ran away. This is not new territory for Gale, who has written about growing up in an abusive cult in her poems, essays, and interviews. Gale, who started Red Hen Press with her husband Mark Cull thirty years ago and now serves as the Publisher and Executive Director, writes of her background in the poem, “The Stoning Circle,” from the collection, The Loneliest Girl.

Ways to leave the stoning circle: Die. Walk away and be shunned and

shamed. Become one of the stoners.

You walk away and are forever shunned by your mother, sister, everyone

you have ever known. You walk away from stones into light and dark.

You leave with a dog on a bailing twine string, a harmonica.

A sleeping bag. Two dollars. A Bible.

You get a job cleaning houses. Your employer attempts to sexually assault you.

You save four hundred dollars for a car. You live in the car” (76).

In Under a Neon Sun, this personal history is transformed into a dramatic fable about rich and poor, about the privileged and the marginalized, throw-away people.

We’ve all read a lot of COVID novels; what makes this different from novels by Patchett and Strout, Cunningham and Erdrich? Under a Neon Sun shows us the stark divide between those for whom the pandemic is disruptive and frightening and those who it threatens to push off the thin tightrope of barely-getting-by. Mia’s employers live in big houses with pools and bunkers. Despite COVID, they hire people to come to their homes to clean and cook, to wash their cars and tend their gardens, to watch and tutor their children, to give them massages, IV infusions for their hangovers, manicures, and pedicures.

In the spring, the pandemic deepens, the race protests grow, and the 2020 presidential election draws near. Mia, her new girlfriend, and her constructed family negotiate the dramatic events and Mia’s understanding of the politics of race and class develop and grow. After she attends her first protest, an employer criticizes her for exposing herself to the virus. “Nobody is ever proud of me, I think,” Mia tells us. “Today, when I stood there with the protesters, I thought, we are pushing back against darkness, against the man stomping on people of color, and I’m here, and I’m doing it too, but now I’m not sure. I can’t even protest for a day without risking my tiny livelihood.” (128)

Always compelling, alternately biting and funny, tragic and hopeful, Under a Neon Sun offers an unusual view into lives of people who are often unseen and unheard. They, and their world, are the beating heart of this story.

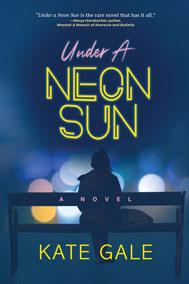

Under a Neon Sun by Kate Gale

Three Rooms Press, April 23, 2024

240 pp. paper

978-1-953103-49-9

Ellen Meeropol is the author of the novels The Lost Women of Azalea Court, Her Sister’s Tattoo, Kinship of Clover, On Hurricane Island, and House Arrest and guest editor of the anthology Dreams for a Broken World. Essay and short story publications include Ms. Magazine, Lilith, The Writer Magazine, Literary Hub, Guernica, and The Boston Globe. Her work, which often focuses on the lives of women on the fault lines between activism and family, has been a finalist for the Sarton Women’s Prize, longlisted for the Massachusetts Book Award, and selected by the Women’s National Book Association as a Great Group Reads..