Review by Rachel Howe

Review by Rachel Howe

Lisa Grunberger is a real working writer whose work spans genres from poetry [I am dirty (Moonstone Publishing, 2019), Born Knowing (Finishing Line Press, 2012)] to fiction [Yiddish Yoga (Harper Collins, 2009)] to playwriting (Almost Pregnant, Yiddish Yoga: The Musical, Evidence). Her poetry has won several awards, including the Moonstone Arts Center International Poetry Contest and the Brittany Stoakes Poetry Prize. That workaday style comes across in her latest collection of largely autobiographical poetry, For the Future of Girls, which was nominated for the Eric Hoffer Book Award and which focuses on the generational trauma of the Holocaust. It wrestles with questions around what it means to survive, in part through one’s children, and what it means to inherit a legacy of survival, particularly for women and girls.

If today’s anti-Semites imagine Jews as part of the secretive, empowered elite, Gruberger’s humble settings of working-class Long Island, with its bicycles, dogs, and dirty bays, and gritty Philly, would not be their best evidence. Here the horrors endured by her grandmother and her father are both exquisitely painful and close the surface – as when her grandmother screams during Nazi-laden dreams – and entirely mundane, part of the fabric of life, intertwined with science projects, mending clothes, first kisses, piano playing, and the simple joys of eating a bowl of pistachios with her father. In “Born Knowing” Grunberger details the way so many children of survivors never had to be told explicit details of the Holocaust to understand their impact. After her nightmares, Grunberger’s Oma (grandmother) never discusses what haunts her, but dresses “in stockings and shoes, a silk blouse and tweed skirt” and makes her coffee, waiting to get on with the day. Nor did Grunberger ever think to ask her about the dreams, “But sometimes when I was very young, I would go to her, sit at the edge of her bed that smelled of over-ripe fruit, yarn and Nivea cream, and press my small hand to her forehead, wet with Hitler’s sweat.” The sensory details do all the work of explaining their relationship and how the grandmother’s history is received by the granddaughter, not with words, but somatically.

While other poems deal less explicitly with the Holocaust, the book as a whole seeks to organize a life and a generation – what are today called second-generation survivors – around the knowledge seeded in their bodies and their primordial memories. The Holocaust is hardly the first time a leader or group has sought to wipe out the Jewish people (the Inquisition, the Crusades), but this most recent example creates a vivid root that grows within Grunberger (and other second gens) and that she passes along to her own daughter. We learn about her daughter, named Rachel after Grunberger’s Israeli-born mother, in the first poem, “Genesis: Beginning the In,” in which Grunberger announces she will “relive her mother backwards” and ends with a scene of rocking the new baby Rachel while recalling her mother’s scent of lilacs and summer in the kitchen. In this way, the book is a kaddish to her parents – lamenting their deaths and the knowledge they are no longer able to pass on to her, and which she, in turn, has not been able to pass along to her daughter. She can no longer ask her mother for almond crescent recipe, nor her father about wearing a yellow star or how to work a sextant.

Sex and womanhood are bound up with the seeds of the Holocaust through Jewish themes and imagery. Several poems (“When Eve Leaves”, “Eve Writ’s Travels”) conjure the wandering Jew, the temptress, the mother, and the creator. Even the pain of abortion, fertility problems, and sexual harassment are told through a Jewish lens but- notable in a book premised on Jewish victimhood – Grunberger refuses to be a victim. She paints a picture of Jewish womanhood as powerful and erotic. In “Moonlighting as Mona Lisa at the Joan of Arc Park,” the narrator and her agent share life’s failures and disappointments, but the narrator tries to be brave: “I do not set flowers at her [the statue of Joan of Arc’s]feet/I climb on top of her, ride her until it’s time to get off.”

This self-empowerment serves her well when Grunberger and her family become the actual victims of a hate crime. In “A Story of the Letter J,” which was first published in The New York Times, a skinhead vandalizes Grunberger’s South Philadelphia rowhome by painting a J on the front wall. The incident pushes Grunberger into closer community with her multi-ethnic neighbors. Her Latino neighbor offers to paint over the offending letter and her daughter trumps hate with kindergarten knowledge, writing a K next to the J, diminishing its power as a symbol of hate as the letter becomes just another building block for the future of a girl.

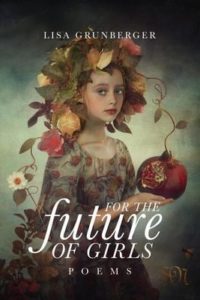

For the Future of Girls by Lisa Grunberger

Kelsay Books, 2023, $23, paperback

ISBN Number 978-1-63980-396-5

Rachel Howe writes fiction, poetry and essays in Philadelphia, where she lives with her partner and four children. Her work has appeared in Lilith, Philadelphia Stories, The Philadelphia Inquirer and more. By day, she is a grant writer and manager. She volunteers as the Vice President of 3G Philly, a group for the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors, upholding their legacy and working to stop antisemitism.