Review by Emily Webber

Review by Emily Webber

If you’ve ever seen shed snakeskin, you’ll know it has intricate texture and patterns, the way the light catches it can make it seem otherworldly. Some see snakes as a bad omen, but the snake shedding its skin indicates transformation and rebirth. Kristine Langley Mahler’s memoir, A Calendar is a Snakeskin, documents the year she turns thirty-eight, during the lockdown of the pandemic, a time of significant global upheaval. She examines how her world is shifting—the demands of being a mother, what home means, her relationship with her siblings and her work, and old ghosts that come to haunt and resurrect fears. Mahler looks for meaning and signs in the world, whether through feathers or stones she finds, snakes turning up in her path, or through astrology and tarot readings. The calendar, the passing of time, is a snakeskin because nothing stays the same—in big ways like the pandemic or the more unnoticeable ways like the slow shifting of relationships.

A Calendar is a Snakeskin is divided into three sections, each an essay comprised of short vignettes. The first is “Ghostwatch”, where Mahler watches and observes the ghosts of her past and present. The second is “Ghostchoke”, where she comes face to face with the ghosts, even describing a physical reaction where she cannot swallow. In the third, “Ghostwatch”, she is transforming her heart and readying it for the future.

I was training the ghosts of my past to line up and float in place; I wanted to study them from all angles, observing without touching, because I did not know yet if I wanted to tell them they could stay.

Mahler picks up a chunk of milky quartz from a canyon in New Mexico and finds the stone’s constant presence provides a springboard for her to question, meditate, and push up against her way of being. She also uses astrology throughout the book as a lens into herself and the world, and as a guide forward. She even admits that it doesn’t matter if any of this is “real”, even the ghosts are all very real for her and facilitate an awakening and understanding within herself.

Mahler’s gaze expands beyond her own interior. She wonderfully details the changing relationship with her siblings. These changes arise not because of any large-scale tragedy or disagreements, but naturally as people age and expectations of what they want from life change. I don’t feel people talk about this enough, and yet almost all of us spend time struggling with it—as our parents age, as our children grow up, or simply when two people suddenly want different things. Mahler’s close examination of her relationships equips her with a better process and language for coming to terms with the absence of what was once hoped for and to fear less the natural end of things and accept new beginnings.

There is the ghost which is the absence of something that once was there, and then there is the ghost of the thing which never filled that absence. The sought that never arrived. The awaited, the expected, the empty. The hole which is never filled. That ghost can be more powerful, more frightening—it is the one that haunts my dreams for longer than those comforts I have known which are now gone.

Mahler is especially fearless in sharing her feelings towards motherhood. In her experience, motherhood is usually described as a constant need to sacrifice oneself for the children. Instead, Mahler shows the difficulty of working and raising children and the constant switching between the two selves, the uneasiness that sometimes comes with presenting your true self to your children. Mahler talks about the need to be away from her children at times—to be alone writing and with her thoughts and to have an interior life separate from her children. She provides a loving home and constant care, but she also needs to care for herself.

My children are growing up, and I am not cleaning or cooking but staring at a screen instead, either absorbing other peoples’ lives or retreading my own. My daughters will disappear into thin air, ghostgirls guarding the random hugs they once gave me, an absence I will only notice when I lift my eyes and reach out my arms to find them gone. I can say this now, and yet I still cannot make myself change. I can regret the heavy burden and refuse to place it on a sled. I must bear this out, the repercussions of being myself with all the faults I do not correct.

Mahler’s memoir shows that our lives are a network—not only of our long-gone ancestors and our living family and friends—but how a hyper-awareness of our interior and exterior world can lead to a transformation of our past selves. And Mahler is not alone in her exploration: The Green Hour by Alison Townsend and Conversations with Birds by Priyanka Kumar are both recent books I’ve read that reflect on the natural world and bring personal insight. And right before reading Mahler’s memoir, I read Cacophony of Bone: The Circle of a Year by Kerri ní Dochartaigh, another book that documents a year during the pandemic and looks to both the natural world and within the self to examine topics of motherhood, home, family, and how we balance both the light and darkness of this ever-changing world. Each memoir excavates meaning in a personally intimate and universal way.

I see it in myself as well. One evening, my son and I walk in our neighborhood, and he finds a perfect feather in his path. The feather’s colors are ordinary brown and white, which indicates it is from one of the Mourning Doves that are common here. Many people consider them a nuisance, but he loves these birds and is delighted. I tell him to keep the bird feather safe in his room and that it will bring him hope and luck when he needs it most. Just as Mahler doesn’t know if her ghosts are real, I don’t know if what I say is true—if a simple feather can hold all that. But I know the feather will help my son connect with and understand his world better and instill a sense of wonder in him. If any good can come from the turmoil and chaos of the pandemic, this renewed connection and desire to examine our lives, along with the natural world, more closely may help us to shed some of the trauma and grief and begin new.

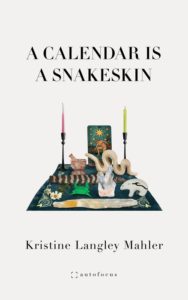

A Calendar is a Snakeskin by Kristine Langley Mahler

Autofocus Books / October 31, 2023

Paperback

9781957392226

Emily Webber has published fiction, essays, and reviews in the Ploughshares Blog, The Writer magazine, Five Points, Split Lip Magazine, Brevity, and elsewhere. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated, from Paper Nautilus Press. You can read more at www.emilyannwebber.com and @emilyannwebber.