Review by Barbara Ellen Sorensen

Review by Barbara Ellen Sorensen

For parents who have lost children, there are personal and highly distinctive similarities in their stories, and there are stark differences. If one is adept at writing non-fiction, one’s innermost revelations will become a helpful blueprint. In Ann McCloskey’s account of her daughter’s death in her book, These Dreams of You, McCloskey has managed the daunting task of creating a pathway from the intimate that leads straight to the universal realm.

Even if you have not lost a child, this book is a hard one to get through. At times, through the unflinching and matter-of-fact tone, I could feel the author’s sorrow. However, “feeling” is a side effect that McCloskey tends to move deliberately away from. McCloskey doesn’t want the reader so much to feel as to understand the devastating effect that mental illness (which manifested in McCloskey’s child, Colleen, through OCD and anorexia at the heartbreaking age of 10) has, not only on the victim, but on her entire family and social network. She purposefully sets up the story to include all of the exhausting and excessive “red tape” a family must endure and wrestle with in order to get proper medical treatment, as well as the sometimes adverse interactions with medical staff, “I, myself, often felt misunderstood and sometimes criticized when meeting with staff members. A social worker, for instance, asked me to stop visiting Colleen every evening. “She needs to separate from you,” he said” (47).

As a reader who has dealt with both the death of a child and a brother with paranoid schizophrenia, I appreciate the thoroughness of McCloskey’s evisceration of the bureaucracy that surrounds and consumes families as they try to navigate systems that often seem set up to test tenacity and resilience: “Another social worker … asked me to tell her about my relationship with Colleen … when I mentioned that Colleen and I had been doing embroidery, she was aghast. “Why would you do embroidery with your obsessive compulsive daughter? Don’t you see how that will increase her tendency towards detail and perfectionism” (49)? The author often had to struggle to rise above comments that may have meant to be helpful but instead landed with palpable thuds of insensitivity and hints of outright cruelty.

McCloskey, admittedly, is no saint and she was not a perfect mother to her daughter, yet it is to the mother that blame is often shifted: “I hated being put in a position of defending myself as a mother. I wondered how much I was being judged for being thin. In American culture, anorexia in teenaged girls is often viewed as a problem that stems from the mother and/or popular culture… I grew so tired of explaining to professionals that I did not own a scale, never talked about my weight, never dieted, and had no women’s magazines or television reception in my home” (50).

Helpful to prospective readers is that McCloskey draws a complete and realistic picture of family life with the mother constantly at the center of a ceaseless whirlpool. The author is not only responsible for the mentally ill child, but oftentimes there are other children, partners or spouses, and aging parents to tend to. “I was feeling pulled in so many directions. Everyone seemed to need me at once, and I felt exhausted by it all. Although I wasn’t always able to keep all plates spinning in the air, I did manage to keep them from breaking. I told myself this was something” (30).

McCloskey’s book interestingly touches on the genetic factor in mental illness and this is something that could have been explored more, from my point of view. “My mother had never been diagnosed with OCD, but it had been clear to me for some time that this disorder of Colleen’s had its genetic roots in my side of the family” (131).

Perhaps the best take-away from this book is the realization that it takes compassion and empathy to deal with the mentally ill and that no one has to do it alone. McCloskey is very clear that as her primary role of caretaker, she was always surrounded by teams and groups of people who tried to save Colleen.

What is ultimately so heartbreaking about this particular story is that love is not always enough. Sometimes you have to let go, McCloskey eventually realizes. “I was … dealing with feelings relating to accepting what was inevitable and letting go of what I once thought ought to be. This was incredibly challenging for me, emotionally. The goal of raising a child is to see her take flight into an adult life, not to watch her decline into an early death with so many unfulfilled dreams” (147). One can only hope that by reading this book, others may be able to muster the strength and courage it takes to face mental illness.

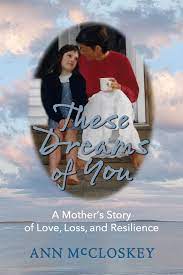

These Dreams of You: A Mother’s Story of Love, Loss, and Resilience

by Ann McCloskey

Green Writers Press 2023

ISBN: 979-8-9870707-3-4

180 pp.

Barbara Ellen Sorensen is former senior editor of the American Indian Science & Engineering Society’s flagship publication, Winds of Change. Sorensen is a contributing writer to the Tribal College Journal. Sorensen has had three books of poetry published: Songs from the Deep Middle Brain (Main Street Rag, 2010), Compositions of the Dead Playing Flutes (Able Muse Press, 2013), and Mary’s River (Kelsay Books, 2018). Her first book was nominated in 2011 for a Colorado Book award.