Review by Jennifer Martelli

Review by Jennifer Martelli

I’ve come to love the epistolary form, which is defined as literary work that reads as a letter or letters. Relationships are laid out on a surgeon’s table, emotions revealed through the mechanisms of the letter. We are allowed into the body of the letter through the salutation: why this is being written and to whom, how the sender ends the epistle. This ancient form has been passed down and used as a literary tool, from Emily Dickinson to Lucie Brock-Broido’s The Master Letters. Two horror gothic novels stand out as examples of epistolary writing, novels that speak to themes of love, abandonment, and grief: Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Frankenstein, the Modern Prometheus, by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley.

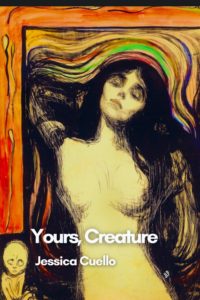

Jessica Cuello’s latest book, Yours, Creature, is a collection of letter poems “written,” by the author Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley to her Creature, to emotional and physical landscapes, but mostly, to her mother, the activist and feminist, Mary Wollstonecraft, who died days after giving birth to her daughter. In the opening poem, “Dear Mother, [I wanted to crawl],” we are shown what this book, much like the novel she will write, lays bare: loneliness, grief, heartbreak,

Dear Mother,

I wanted to crawl back into the black interior

of you, womb scratched by an animal—

I wondered if we didn’t know the story of Victor Frankenstein and his monster—even if we had never seen the Karloff movie—would we appreciate these poems. Cuello’s genius structure allows for storytelling; each section is titled with a line from a poem that serves as a guidepost, followed by a short time-line explanation of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s life (from her birth, to her affair and marriage to Percy Bysshe Shelley, the death of her infants, the writing of her most famous novel). Cuello also includes extensive notes—one of my favorite parts of any poetry collection. But, most importantly, Cuello uses the signature lines and salutations of the letter form to relay an emotional narrative. Although most of the letters are addressed to “Mother,” Cuello’s salutations direct the reader through Wollstonecraft Shelley’s journey of creation. We are given geographical movements through Europe, which lead to the writing of Frankenstein. The poems addressed to “Dear North,” “Dear Sweden” lead us to the “Dear Creature” poems. The letters’ ends allow the reader to know the relationship of the sender (“Your daughter, Mary Shelley” “I who copy you, Mary”); the emotional desperation of a child (“With longing for your presence, Mary Shelley”); the distress over her relationship with Shelley (“No one lived happily ever after, Mary Shelley,” “Your pregnant daughter, M.S.”), to the creation of the monster (“Your monstrous creator, M.S.”).

Through these letters, Cuello blurs the membrane between creature and creator. We wonder who the monster is. Even as a suckling, the infant was supplanted by animals:

and to expel the placenta

puppies sucked the milk

your body meant for me—

Your daughter,

Mary Shelley

This act is echoed later in the book, after the death of her own child, where the act of creation is reversed,

What is it to make a life

that dies—like god

it cannot stand to stay

Cabbage leaves are soft

like cloth and smell of tea.

I wore them on my breasts

like medicine.

Childbirth makes her “hate her flesh” in her letter to her mother where she describes herself as being “sewn from gut to brain/with scraps of men.” In “Dear Creature, [The sea of ice],” the letter is signed, “Your monstrous creator, M.S.” Birth—her own and the deaths of her children—is described in terms of Frankenstein’s laboratory. We’re presented with the image in “Dear Creation [The porcelain basin]”

In the beginning

of basins I started my life laboratory:

either the mother-death

or the washing of a child

in a basin of red.

The Creature, who in the end of the novel is isolated on an Arctic floe, is recalled with the imagery of motherhood, punishment, and abandonment. In “Dear Mother [I am always looking],” the “grieving daughter, Mary,” writes,

I tried to make a man

encompass three: William, Clara, Percy.

There was one that tried to kill me:

nameless.

I wanted it to be my murderer:

little vengeance of your death:

little redress of adultery.

P. plunged me to the waist in ice

and I froze at last.

This theme of vengeance for her affair with Percy Bysshe Shelley is entwined with Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s desire for love, born from the first abandonment (and guilt) of her mother’s death, her father’s rejection because of her affair, and Percy’s own infidelities (perhaps with her stepsister). In “Dear Mother [My stepsister has changed],” Mary confesses to her mother

I wouldn’t tell anyone else:

I want this baby to make him love

the way he did.

Pregnancy has snagged me up,

//

changed my space. Like his wife

I am isolated with my womb.

did you know G. would turn

on me when I broke the rules?

Like the monster to whom she writes—and in identification with him—in “Dear Creature [After everyone forgot],” she signs off with “Your monstrous maker,/M.S./(Do you know P. ran from our infant who was born too early).” These themes of loneliness and abandonment elevate Frankenstein from a simple horror story. In Yours, Creature, the abandonment and loneliness is circular, like a noose. In a letter to “Dear Creature [Father won’t see],” Cuello recreates the scene in the novel where the creature is unable to join the family he loves,

I put you there, Creature,

outside the cottage and the woods,

as Jupiter has rings of gas

so none may enter.

This desperation for love, this “grief bucket,” is what creates the “monstrous toddling from bed/with an open mouth, a devil girl. . .” who was had been cut loose, by “the mother, the father/the holy lover.” In this letter, “Dear Rejection 1815,” Wollstonecraft Shelley confronts rejection:

His face was the only male face.

Absence always could subsume me,

powered as it was by the first rejection:

God’s holy three of No No Never.

The intensity of emotion in the epistolary poems of Yours, Creature is as recognizable and monstrous as Frankenstein’s Creature. Jessica Cuello’s poems convey a truth I’m not sure could be contained in any other form. How does a heart not break after reading

Creature, how female

I made you

peering at the family

& gathering their wood—

But they don’t want you.

Jessica Cuello has created a body of work that tells a story of love in all of its destructive and creative manifestations. Cuello sends us timeless letters from a woman who “is damage/and witness strung invisibly/from baby to man.”

Yours, Creature by Jessica Cuello

Jackleg Press

May 15, 2023

Pages 110; Paperback

9781737513438

Jennifer Martelli (she, her, hers) is the author of The Queen of Queens (Bordighera Press, 2022) and My Tarantella (Bordighera Press). She is also the author of the chapbooks In the Year of Ferraro (Nixes Mate Press) and After Bird, winner of the Grey Book Press open reading, 2016. Her work has appeared in The Academy of American Poets Poem a Day, The Tahoma Literary Review, Thrush, Cream City Review, Verse Daily, Iron Horse Review(winner, Photo Finish contest), and Poetry. Jennifer Martelli has twice received grants from the Massachusetts Cultural Council for her poetry. She is co-poetry editor for Mom Egg Review and co-curates the Italian-American Writers Series.