Interview: Neema Avashia Lives in Another Appalachia

Interview: Neema Avashia Lives in Another Appalachia

by Kristen Paulson-Nguyen

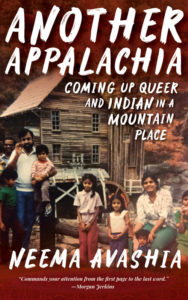

Neema Avashia is the author of Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place, which was released from West Virginia University Press in March 2022. Much of her writing pertains to the unique experience of growing up as a member of a tight-knit Indian community in West Virginia, where Indian community members comprised less than half of one percent of the state population. Avashia’s essays have been published in The Bitter Southerner, Kenyon Review Online, and Cosmonauts Avenue, among other outlets. She recently read her work at Lit Crawl Boston, part of the Boston Book Festival. Kristen, who shares a neighborhood with Avashia, spoke with her about how she wrote and assembled her memoir in essays––and the decisions she made on her path to publishing the book.

Kristen Paulson-Nguyen: Why did you want to publish a collection of essays?

Neema Avashia: I really love the essay form. An essay begins with a question spiraling around in my mind that I’m trying to answer. My whole life, I’ve been a questioner. So, I think the essay aligns well with my personality. It’s the form in which I learn the most about myself. It’s also the way I think I work best. I don’t necessarily have an answer to the question I ask in an essay, but I can juxtapose experiences from my life with moments in literature, or things I’ve observed in the world, to get closer to an answer.

KPN: What questions were you trying to answer with the essays in Another Appalachia?

NA: So many questions! What is it like to develop a coherent sense of identity when you are living in a place where there are so few visible representations of people like you? What does it mean to have a deep love of a place whose policies increasingly demonstrate that it does not love you back? How do you continue to hold deep love for people whose beliefs have become increasingly disparate from your own, and in some cases, those who explicitly wish ill on people like you? What are the lessons from my Appalachian upbringing that I carry into my present-day existence in New England? What lessons can each of those geographies learn from the other? How do we push back against the notion that any one narrative can be a definitive representation of a place or its people? What are the markers of belonging and community, and why can both feel so perpetually ephemeral?

KPN: The form in which those lines of inquiry appear in the book fascinates me. Why did you decide on an essay collection as opposed to the single-strand narrative of a memoir?

NA: In a memoir, the reader rightly has more of an expectation of an answer to a question. I don’t have any answers. In fact, it has taken me forty-three years to find the questions. In memoir, there is a coherent arc. I didn’t have that level of coherence about my story or my identity. In a lot of ways, it is through writing Another Appalachia that I’ve been able to locate a sense of coherence. Maybe when I’m seventy-five, I’ll say, “Okay, I’m ready to write a memoir.” I’ll have the coherence. I’ll have the answers to the questions.

KPN: That makes sense. Did the themes around which your essay collection is structured come first? Or did the individual essays, some of them previously published, lead to the creation of a collection?

NA: A number of the essays came before their thematic links. In 2015 and 2016, I just really needed to be writing. I didn’t know I was writing a book. J.D. Vance’s book, Hillbilly Elegy, came out in 2016. It was a kick in the ass with regard to how Appalachia was being represented to people outside the region. His supposedly definitive narrative of Appalachia didn’t align with anything I knew. I wanted to write about the home I know and how it continues to shape me. To offer some insight into another Appalachia—a different one than Vance had rendered. As I put the collection together, I was relying a lot on the assignments I received in writing classes I took at GrubStreet. A lot of the lyric pieces in the collection had their roots in workshop assignments. For one assignment, we were asked to write a hermit crab essay. This became the essay, “Directions to a Vanishing Place.”

KPN: I loved that essay. It made sense to me that you placed it first in your book, almost as if to orient the reader to West Virginia. How did you begin to see the themes of your other essays emerge?

NA: My essays’ themes began to emerge in conversations with classmates. People started to say, “There are themes that are coming up across essays.” A strong feeling I have is that being in community around your writing is very important. There wouldn’t be a book without the members of my writing community. They listened and read and said, “These are experiences we want to know more about.” As a result of their attention, I began to be more intentional about essays that had thematic links.

KPN: I’m glad you had a strong community of writers who shared their insights. To return to your mention of Vance’s book, you said his vision didn’t align with the Appalachia you knew. What was the other Appalachia you wanted to name and articulate for readers?

NA: Vance delivered a flat portrayal of Appalachian people as poor, white, working class, and struggling because of their choices as opposed to systemic abandonment by government and corporations. I knew I didn’t agree with that. I wanted to tell different stories. There have been Black folks in Appalachia for centuries. Immigrants in Appalachia for centuries. Queer people, too. Folks who work in the chemical industry, instead of in coal. Folks with PhDs and MDs whose immigration to the United States was predicated on working in places like Appalachia. Maybe the numbers haven’t been high enough to garner visibility on the national level, but that doesn’t mean we aren’t here, or that our stories don’t matter. When mainstream media latches onto one narrative as emblematic of an entire region, it erases so many people. And that erasure is a kind of violence; it allows the rest of the country to write off Appalachia, instead of fighting for the humanity of the full range of people who live there.

KPN: You completed several essays in 2016. What steps did you take next?

NA: In 2016, I knew I was writing stories about my Appalachian upbringing. In 2017, I went to the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop as a student and started to push further into those stories. I got invited back in 2018 as a Peter Taylor Fellow. Geeta Kothari was my instructor the first year and the person with whom I worked as a fellow the second year. Geeta started looking at the essays I had drafted. Hearing her perception of the changes in my writing from one summer to the next was so helpful. I started to think, “I can see this as a book.” I also thought, “I can see how much more there is to do.”

KPN: What was the application process for the Kenyon workshop like? Do you have any words of encouragement or advice for writers applying to residencies?

NA: The process is pretty straightforward. You write about why you want to attend the workshop and share a sample of your written work. One thing I think is important to note is that workshops can really vary in what they offer writers. At some, you workshop a piece you’ve already written. What makes Kenyon Review Writers Workshop unique, and for me in particular, so important, is that it is a generative workshop. You are asked to write new material every single day and to share with the community during your time there. The goal is creation, and being in that space can really spark so many seeds for the writing that comes afterward. I think that in general, any opportunities you can find to dedicate stretches of time solely to your writing are such gifts. The disruption to normal routines creates an open space where you can just focus on your ideas and your words and give them the time they deserve.

KPN: Did you meet people at Kenyon who became part of your writing community?

NA: Yes. Many strong relationships have emerged from attending KRWW. Folks who have been real cheerleaders of my work and who have lifted it up in their own reading and writing communities. Folks who have continued to share work with one another long after the workshop was done. One of my classmates from last summer’s workshop drove from Cleveland to Pittsburgh for my book launch there, which was such a lovely moment!

KPN: That’s amazing! I’d love to hear more about the mentorship you found there, too. What were some of Kothari’s perceptions of your writing as it developed? How did she help you develop it further?

NA: The biggest thing she noticed over time is the shift in the confidence of my written voice. The way my communication of ideas moved from being tenuous to being clear. And the ways in which, largely thanks to her teaching, I was better able to reflect on the stakes and the costs in the stories I was telling. It was Geeta’s feedback that really helped me to move from writing about situations to telling full stories.

KPN: Did having Kothari’s support also build your confidence in your work?

NA: Yes. She gave me so much confidence. When you’re writing a book, you need someone to say, “This can be. You’re on the right track.” Geeta has done that for me at every turn, from saying that my words had worth to reminding me again and again that my book would find its readers. I call her “Bookstradamus” because she has possessed a clarity about my book’s success from the outset that I have never felt certain of in my own mind. If you see her, you should ask to see her “Bookstradamus” t-shirt!

KPN: I will. I love that word. What strategy did she recommend?

NA: She advised me to place essays in literary magazines but also in general interest publications. She encouraged me to think about where my essays fit. She said, “Don’t submit to one thousand places randomly. Read journals and magazines and try to think about where your work best aligns. Figure out which essays fit where.” She encouraged me to take bigger swings with placement to build an audience.

KPN: Yes. This goes back to what you said earlier about community and how your writing community helped you see the themes in your essays. Can you talk about a publication where you placed an essay that became part of your book?

NA: Yes. I started to think about where the essay, “Be Like Wilt,” which became part of my collection, could go. I began thinking strategically. I asked myself, “How do I publish in a range of places that hit different audiences to show what my writing can do?” The Bitter Southerner’s audience is Southern progressives. It has a large readership. If people liked the essay, it would tell me something about an audience with whom my broader work might resonate. So, I published “Be Like Wilt” first at The Bitter Southerner in 2019. And just a few weeks ago, The Bitter Southerner included Another Appalachia in their 2022 Summer Reading Roundup. So that pressure test turned out to be sound!

KPN: How did you decide the order in which to organize the essays?

NA: One of the readers had recommended organizing it into three sections: In “Appalachia,” “Away,” and a third category that I don’t remember. And I tried, but what I found is that those lines of distinction weren’t clean. A lot of essays jumped back and forth between those lines. Ultimately, I decided to think of it as a memoir in essays and organize the collection in a chronological fashion. I roughly organized the essays by their inciting moment to determine where they would go in the collection, from Appalachia to Boston. An essay where the lines become clean is “City Mouse, Country Mouse.” I decided that present-time stories could only be included if they had resonance to the past. I asked myself, “Does my past experience shine a light on the present?” It had to be connected. Up to “City Mouse, Country Mouse,” things are grounded in the past reflecting onto the present. After that essay and onward, I’m in the present reflecting on the past.

KPN: Your collection was published in March 2022. Congratulations! As you promote your book, what have been the hardest essays to talk about with audiences?

NA: The hardest essays to talk about have been “The Blue–Red Divide” and “Chemical Bonds.” They keep me up at night in terms of really wanting to hold the people within them with empathy and being worried I haven’t. I’m worried people aren’t going to see the love that’s there, because of the pain that’s there. Those are the two stickiest essays in the collection, the ones with which people resonate the most. People don’t often talk about their sticky relationships, what makes them hard and complicated. People struggle alone. These essays are a window into a thing we don’t talk about a lot.

KPN: They certainly open the door to difficult but important conversations. Speaking of which, what does it feel like at a reading to talk about yourself and your writing?

NA: [Laughs.] You know, when I was writing the book, I never fully comprehended what it would mean to share it with audiences in person. So, I wrote this deeply personal, vulnerable book, and now I have to share it with the world. In person. And when you’re at readings, people are only asking you about you—your life, your stories, your words—for an hour and a half. So now I’ve realized, “Oh, now we have to talk about it. And talk about it. All my feelings about everything.” It’s been powerful, though. I think the vulnerability present in the book makes space for vulnerability in the room. People have really brought their fullest selves, and their most honest questions and reflections, into the room with them. And I’ve been so grateful to share space with readers who want to talk about the same hard things that I do!

KPN: I’m happy for you, that you have been able to do that. And I’m grateful that you took this time to speak with me about Another Appalachia. Thank you.

Another Appalachia – Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place by Neema Avashia

West Virginia University Press, 2022, 168pp

PB 978-1-952271-42-7

$19.99

Kristen Paulson-Nguyen is Hippocampus Magazine’s Writing Life Editor. Kristen and Neema met when Kristen organized a reading about identity in opposition for Lit Crawl Boston 2022. On June 9, the night of the Lit Crawl, Neema cracked up the crowd with her essay, “Be Like Wilt.” Kristen continues to be inspired by her fellow writers as she creates. Her essay, “Liza in 17 Fragments,” will appear in the fall print issue of Solstice Literary Magazine.

Kristen Paulson-Nguyen is Hippocampus Magazine’s Writing Life Editor. Kristen and Neema met when Kristen organized a reading about identity in opposition for Lit Crawl Boston 2022. On June 9, the night of the Lit Crawl, Neema cracked up the crowd with her essay, “Be Like Wilt.” Kristen continues to be inspired by her fellow writers as she creates. Her essay, “Liza in 17 Fragments,” will appear in the fall print issue of Solstice Literary Magazine.