Review by Laura Dennis

Review by Laura Dennis

We usually hear “Hallelujah” as a joyful chorus, a sort of incantation expressing gratitude to the divine. In Hallelujah Science, however, poet, performer, and Cave Canem fellow Kelli Stevens Kane incorporates it into a new song that weaves myriad other spells.

That is not to say spirituality is absent from Kane’s debut poetry collection, a work 10 years in the making. The poem “(59),” for example, opens with the proclamation “She is risen,” which both echoes Christian scripture and demonstrates the embodiment with which these poems are infused. “(59)” takes us from resurrection to angels, then back to earth, where the speaker suffers from fever–a recurring motif–, before veering into auditory, visual, and tactile imagery that verges on the hallucinatory in its repetition of texture (“wooden”) and sound (“wood” / “would”).

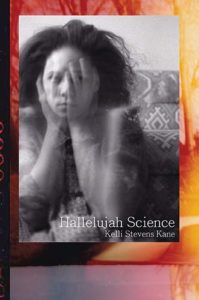

This movement in and out of clearly delineated worlds is prefigured by the self-portrait on the cover. The photograph’s blurred lines, produced through multiple exposures, create a sort of scrim through which the reader can almost discern the subject. Almost. Similarly, the poems themselves move between black and white, past and present, life and death, as in “(40),” where the speaker juxtaposes death with a list of ordinary things she will miss.

Kane often cuts to the heart of things in the manner of haiku or perhaps more aptly, nursery rhymes. Her play with words and sound, along with sometimes deceptively simple language, in part reflect her time as a preschool teacher, which she says helped shape her poetry, including 2-line poems such as “(74)”:

take the lid off the blender while blending

and know that a splatter is pending

This is not to say all is fun and games. The image of the blender in “(74)” finds a sort of off-kilter echo in the surreal imagery of “(18),” where the speaker imagines twisting her head off “like a thermos lid.” Such graphic intensity also finds its way into poems on fertility, another recurring theme. The almost savage desire expressed in “(22),” for example, flows into the longing of “(23),” the harsh plosives of “take,” “blood,” “put,” “back,” and “egg” giving way to the softer, humming alliteration of “myself,” “mama,” “imagine,” “my,” “make,” and “milk.”

If I could take the blood

and put it back on the walls

and take the egg

and put it back in the blood

and take the seed

and slam it into the egg

I would

I would make myself

a mama. [“(22)”]

—–

myself a mama

imagine that

my baby cries for my milk

I make milk, myself

a mama [“(23)”]

As readers may have already surmised, the numbers in parentheses serve as poem titles, though perhaps not in the way one might expect. While “(22)” and “(23)” flow together consecutively, this is the only time this happens in the anthology. Moreover, they are actually the 44th and 45th poems out of 50 (51 if one includes the “contents,” which read like a poem and have been published as such). The other poems are introduced by numbers ranging from 1 to 86, beginning with “(9)” and ending with “(66).” It is easy to get caught up in wondering what, if anything, this means, yet it makes its own sort of poetic sense. After all, we tend to think of numbers as quantitative, a reliable form of data. We forget that they cast their own spell, that they too constitute a language open to interpretation and transformation.

The author offers an additional explanation in a 2011 interview, saying that the non-sequential numbering reflects the fact that we do not live in a predictable, rational, orderly world. She goes on to say that she loves numbers, which is unsurprising for someone who, in addition to writing poetry and teaching nursery school, has also worked as an accountant. Other hats include those of oral historian and playwright who has performed her one-woman show, Big George, nationwide. I recently had the good fortune of hearing Kane read at an online event hosted by White Whale Bookstore in Pittsburgh, her home town. The expressivity of her performance confirmed what the poems themselves convey–magic happens when we push the boundaries of language and dissolve the space between worlds.

Hallelujah Science by Kelli Stevens Kane

Spuyten Duyvil, 2020 $15.00 [paper]

9781952419379 [paper]

Laura Dennis is a college professor in Appalachia. She manages and writes for the Attachment & Trauma Network (ATN) blog and reviews books for academic journals as well as Mom Egg Review and Still. Her own non-fiction has been recognized in a variety of outlets, including writing contests, Bethlehem Writer’s Roundtable and Kentucky Philological Review.