Review by Lara Lillibridge

Review by Lara Lillibridge

According to the book jacket,

Kathryn Nuernberger is the author of the poetry collections Rue, The End of Pink, and Rag & Bone. She has also written the essay collection Brief Interviews with the Romantic Past. Her awards include the James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets, a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, and notable essays in the Best American series. She teaches in the MFA in Creative Writing program at University of Minnesota.

However, I much prefer her own website’s description, “Kathryn Nuernberger is an essayist and poet who writes about the history of science and ideas, renegade women, plant medicines, and witches.”

The stories of witches truly are the stories of renegade women, and, it turns out, the history of systematic and sanctioned abuse of marginalized people by those in power.

Nuernberger masterfully draws parallels between the witch trials and modern day persecution in beautifully lyrical prose. Just as “No aspen tree is just a tree, each is also a limb rooted into a much larger body that is an entire forest breathing together” (1) so too is no witch just a witch, but instead one of many mowed down in the name of righteous society.

For example, in the essay Agnes Waterhouse, Nuernberger juxtaposes Agnes’s trial testimony with present day abuses of power:

Her daughter Joan, for instance, was induced to confess she had seen her mother turn that cat into a toad. Why turn your demon cat into a demon toad? You might as well ask why a police officer would kill a man for selling cigarettes or taking out his wallet or carrying a cell phone, living in his apartment, or opening his own front door. The child went on to admit she sold her own soul to that selfsame toad so she could get a bit of bread and cheese from the neighbor girl, Agnes Brown. (13-14)

And in this way, Nuernberger forces us to confront present abuses by showing us that:

It seems to be easier for some people to understand the role of stereotype threat and implicit bias in the judicial system when I say the wrongful imprisonment and execution happened to a little old white lady, gullible and confused, possibly suffering from dementia, named Agnes. (15)

In going back to her website description of, “plant medicines, and witches,” while this book does contain many various descriptions of the like, she explains that,

I started reading about witches because I thought I’d find people talking about how they felt this green world offering to take over their bodies if only they could figure out how to let it. But what I found was just the usual politics and patriarchal bullshit. (68-69)

And I love that Nuernberger doesn’t shy away from profanity, but also sent me to the dictionary for a few words with which I was unfamiliar—I’m looking at you, phenomenology. It is a smart book, yet down to earth. Cerebral, yet artistic.

This book moves from a living history of atrocities into the deeply personal as well. Nuernberger contemplates leaving her husband and delves into to the universal anguish and frustration of trying to share a life with another. Yet she does it with a deft hand and an awareness of her own dramatics:

The hill was a surprise garden of harebells, anemone, and wild mustard. Or it was a weedy entanglement of poison ivy. It was both, of course, but another name for my experiment was ‘I only believe in my version of reality.’ The results of this field research: he was pissed and I was pissed. (112)

As the book continues, we start to notice that this inventory of atrocities is not just on behalf of others. Below the surface, there is another story, never completely defined.

Nuernberger alludes to, “Liabilities and vulnerabilities and responsibilities that include what I can and cannot say to you now.” (149)

Does it matter what she cannot say?

I say no, it doesn’t, in the same way that knowing what was said or not said in the public record of all these witch trials does not tell us anything about what was in the heart of the persecuted. As she explained about the witch Johannes Junius:

He feels so guilty about how he couldn’t seem to translate his humanity into a language that his judges, from within the peculiarity of their official positions on a panel, would understand as human. (178)

It is obvious, that she too cannot translate her humanity into a language understood by those in power, and this missing story can therefore be filled with any story of any woman or marginalized person. The absence contains all of our martyrdoms at the hands of the falsely-righteous.

Witch of Eye is a stunning book of essays, at turns contemplative, and vehement in its insistence that we not look away from not only our history, but who we as a society still are today

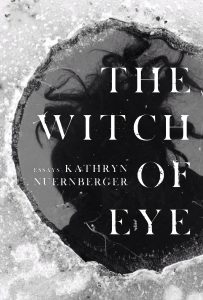

The Witch of Eye: Essays by Kathryn Nuernberger

Sarabande Books, 2021, 203 pages, $16.95 [paper]

ISBN: 1946448702

Lara Lillibridge is the author of Mama, Mama, Only Mama (Skyhorse, 2019), Girlish: Growing Up in a Lesbian Home (Skyhorse, 2018) and co-editor of the anthology, Feminine Divine: Voices of Power and Invisibility (Cynren Press, 2019). Lillibridge is the Interviews Editor at Hippocampus Magazine and a mentor with AWP’s Writer to Writer program.