Review by Cammy Thomas

Review by Cammy Thomas

If I remember correctly, there’s a moment in the movie Zorba the Greek when the callow English youth asks Zorba, the wise old Greek, whether he’s married. Zorba, with some humor, says he’s a man and a fool, so of course he’s married, “wife, children, house, everything—the full catastrophe!” Emily Mohn-Slate’s The Falls is a woman’s take on this full catastrophe. (Perhaps it has a little something in common, also, with the English tv comedy, Catastrophe, about a man and woman who decide to try to raise the child when she unexpectedly becomes pregnant.) In a book of many moods, which examines her two marriages, and her early motherhood, Mohn-Slate explores her responses courageously, admitting her exhaustion, her boredom, her fury—but also her love, devotion, and gratitude. Despite some rough waters, the sea is beautiful and holds her up.

Emily Mohn-Slate’s book, Feed, won the 2018 Keystone Chapbook Prize from Seven Kitchens Press. An MFA recipient from the Bennington Writing Seminars, she teaches high school English at Winchester Thurston in Pittsburgh. The Falls is her first full-length poetry collection.

This new book coheres partly because there’s one poem in each of the five sections addressed to the now mostly forgotten Victorian and early-Modernist English poet, Charlotte Mew, who died a suicide. Mew never married, dressed in men’s clothes, and wrote enough to be noticed by some of the best poets of that time. Virginia Woolf admired her work. Mohn-Slate imagines Mew’s liberation: “…I passed the London Pride parade./ I imagined you holding Ella or May’s hand/ instead of your own faded lapel.” And she encourages Mew to do what she herself needs to do: “Charlotte, can you smell the sea?/ It’s not far off. Out there, you can float for miles,/ try out your voices on the wind” (34).

Summoning a non-conforming female voice to assist her in exploring the roles of wife and mother helps Mohn-Slate resist some aspects of those roles. This resistance appears elsewhere in the book, as when unlike elements crash uncomfortably against one another. So in “Maybe,” she juxtaposes an email she receives about phases of pregnancy, “you may be able to feel the baby’s kicks” (42), with stories of dead workers pulled from an abandoned, illegal gold mine, a young woman hacked to death in Delhi, a plane missing over Nepal. Many things in life are horrible, and yet life goes on, at least somewhat pleasurably. And a mother keeps being a mother.

It’s not just the outside world that is violent—it’s the speaker’s own thoughts, too. In the book’s first poem, the new mother says, “I forget things so often now./ I never forget my glasses./ It would be so easy to forget the baby” (13). As a first poem, this is unsettling, privileging the glasses she needs to read by over the life she’s responsible for, but by the end of the book, we recognize an exhausted mother determined to keep writing; and if honest, many would affirm that her escapist fantasies, “A woman drove off with her baby on the roof of her car” (13), are not unfamiliar. “I never meant to be so needed,” the speaker admits in “Feed,” “I dream about drifting alone/ I can’t quiet my ambition” (57). She’s honest, not despairing—not exactly blaming herself, just reckoning.

The poems come in many forms—some looking almost like blank verse, others right-justified with short lines, still others spread out on the page sometimes without punctuation. Like the poems’ subject matter, these varied forms suggest that we need not be trapped by what we’re doing but can work and express ourselves in many modes. That said, the common thread in this engaging book is clear and forthright speech. Listening to the noises her mother’s new hip makes, the speaker says:

…each time she steps,

the part the grease can’t reach

creaks. Each step,

she swings, curving like a bell,

ringing out, I’m mortal I’m mortal,

and so are you.

Ah, that’s it—yes, we are all mortal. The menaces of life never disappear. In the title poem, a woman on her honeymoon falls into a huge waterfall and almost dies. From her hospital bed, she says, “I wanted/ to touch beauty.” Don’t we all.

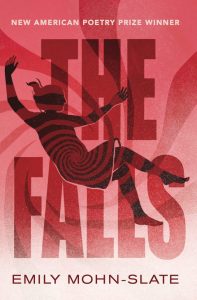

The Falls by Emily Mohn-Slate

New American Press, 2020, $14.95

ISBN 9781941561232

Cammy Thomas’ first book of poems, Cathedral of Wish, received the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America. It was followed by Inscriptions, and Tremors is forthcoming in 2021, all published by Four Way Books. She lives in Lexington, MA.