Review by Ana C. H. Silva

Review by Ana C. H. Silva

I read Rage Hezekiah’s Stray Harbor as a newly (early) menopausal person, so tears don’t spring up in my eyes as readily as they used to, but goodness did they try. Her language is direct, honest, precise, pulling into itself her vast reaches of life experience and imaginings. I learned beautiful, perfect words I feel like I should have known forever, like “sororal” and “accroach.” A single poem, image-packed, can make quick turns, compress whole stories, story-tell in quiet filmic zooming ins and outs during the short spaces between stanzas.

Rage Hezekiah, a MacDowell, Cave Canem and Ragdale Foundation Fellow, received the Saint Botolph Foundation Emerging Artists Award, and her 2019 Chapbook, Unslakable, is a Vella Chapbook Award winner. She also worked as a farmer, baker, and doula, and the collective wisdom of all that juicy, life-affirming, heart-breaking work is within Stray Harbor. In An Interview with Rage Hezekiah she explains that she chose the title for the way it conveys “the tension between feeling abandoned and being held.” I know I felt held by these poems, by the spell of their honesty, by the way she wrenched open old boxes of pain with her own two arms, airing everything out with the salve of words and renovating touch; likely composting the contents to grow some of the farm stand carrots she will eat later on.

This collection is as rich as heritage. The speaker investigates her childhood, pulling out the good with the bad. Hezekiah unshrouds racial and cultural wounds as she investigates elements of her racial and ethnic background, which includes Carribean, Black, and Irish Catholic descent. Many of her poems capture the ethos of the messy, freshly-liberated mode of the 1970s-era woman who has broken down doors for herself but whose “Feminist Safe House” does not hold enough room for her children. I’m certain the poet is speaking for a generation here, although these poems are grounded in particulars. There’s the fear of being forgotten by parents preoccupied by their own demons; there’s also tenderness, love mixed into the baking of a cake. (The sibilance and alliteration of “Layers,” compelled me to read the poem aloud. My usually indifferent cat, who overheard my reading, showed me her warm belly in reward — not making that up.)

Cove, the first section, acknowledges the real and dangerous divide between grown ups and the children who live in their wakes. “Kitchen Children” understands the way love can live alongside abuse, and wonders which legacy will win out.

My father mourns the soft, pink palms of this man’s hands,

Who gifted him reticence and welts from belted leather.

He only remembers waterfall sounds

Of seed poured in the feeder, piquant curry smells,

How many times he lay the spoon

In sweet repose between the burners (6).

As I read Cove, Bay and Sound, it was rewarding to chart water and waterways. Wetness often seems to evoke the rush of life, adventure. In Bay, the second section, we see this happening in the wet ground of the muddy shore before the magic mushroom ride in “Psilocybin,” and, more subtly, in what happens after the dawn warms wet hay beneath their feet in “Dozen”:

I think: Yes.

I would wait quietly too,

my eyes closed knowing

she would come every morning;

the grasp of her hand

below my body’s down,

retrieving what I’d made

while she was sleeping (36).

The speakers in this section are sensuous, tender, but still ready to fight like the dog in “Playing Fetch” who keeps his teeth clenched on his ball. Hezekiah often takes an empathetic dive into the animal. Or perhaps, she is letting those animals tell us something about who we are; we are also nature.

Hezekiah revels in the robust, irreverent, vibrant queer landscapes she frequents, in the women she has loved. In Sound, the third section, her nouns alone do the work of a thousand pictures. For instance, the lover’s neck in “In the Walk-In,” is

a gloaming

redolent

meyer lemons

heirloom tomatoes

fresh sage (48).

She holds that woman’s face in her hands, reminding us of an earlier poem where someone else’s fingers warms her chilled, rage-filled, six-year-old earlobes. Contact is healing, whether with human bodies or water bodies, and key to finding our inherent power. In the bittersweet, defiant “Brooklyn,”

we wash our laundry

in the shower, fill the tub with ripped jeans

smelling of patchouli and cedar, a dose

of Dr. Bronner’s soap. We agitate

suds with our feet as though we’re stomping

grapes into wine (44).

The punk-girl bassist with the angular blond bangs in “Androgyny,” could be the cover girl for this section with

Her fingers firm

against the neck and fretboard

of her Fender, head bowed

in reverence to her own

powerful hands, summoning song (49).

Rage Hezekiah summons harvests of song in Stray Harbor, gathering up giggles and earthen smoke, breaking dishes and salted-cold air, lust and wet wool, to play together in this tremendous collection.

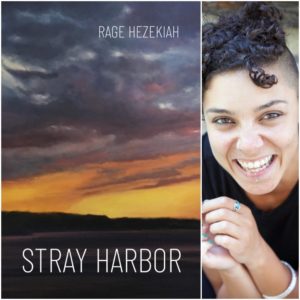

Stray Harbor by Rage Hezekiah

Finishing Line Press, 2019

ISBN Number: 1646620135, 9781646620135

Ana C.H. Silva is a poet who lives in NYC and the Catskills. Her chapbook, One Cupped Hand Above the Other is with Dancing Girl Press. Another chapbook, While Mercury Fish, is forthcoming from Finishing Line Press. She writes for the Mom Egg Review Gallery.