Review by Laura Dennis

Review by Laura Dennis

Back in graduate school, I discovered prose poet Francis Ponge, who famously said, “Another way of approaching the thing is to consider it unnamed, unnamable.” I was fascinated by his way of looking at the world, his wit, and his use of words. Sadly, I could not linger over his work, what with all the other titles on my reading list and the exams that loomed ahead. Ponge came to mind again, however, as I immersed myself in Sarah Wolfson’s début poetry collection, A Common Name for Everything. Although Wolfson’s work is very much its own–dare I say it–thing, I found similar pleasure in her love for words, sense of humor, musicality, and experiments with form.

Wolfson, who has been published in a variety of journals and twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize, divides these 42 poems into four sections: “Have You Been to the Place?” “Little Here, Little Now,” “Earth-Things,” and “Beginnings.” The book’s press release likewise mentions four themes: nature, home, parenting, and naming. My initial plan was to try to link each of these themes to one of the book’s four sections, but I quickly abandoned that idea. This was not because those themes aren’t present, but rather because they’re omnipresent, bouncing off each other in the most unexpected places, like melodies echoing throughout a musical score.

Indeed, “unexpected” is one of the first words that springs to mind to describe this collection. Sometimes, dictionary in hand, I would marvel at the depth and precision of Wolfson’s language. Other times, I would let my brain puzzle over the myriad ways to connect what sometimes felt like wildly disparate dots. Still other times, I rode the flow, letting the sounds and images carry me from one line to the next, much as one might observe one’s thoughts in a mindfulness meditation. I often sensed a mind a bit like mine at work, someone who loves words for their own sake and takes deep pleasure in appropriating new ones.

I finished the book feeling both more knowledgeable about and more in harmony with everything from sheep to mammoths, apples to mangroves, mollusks to lions, the Pleistocene to Pluto. Nature is shown from many angles: historical, academic, personal, scientific, literary, humorous. Consider, for example, this passage from “An Unfunded Study of Milking and the Moon:”

Metcalfe acknowledges poetry a little

when she concedes all estimates about

mammoth tooth growth must first

go through what we know about

the African Elephant. Metcalfe is herself

an ungulate in name. I imagine

it must be hard to love without the moon.

For Metcalfe, I assume, dating is mostly

the radiocarbon variety, but who’s to say

what is and isn’t propagatory. (31-40)

As the line breaks and enjambments above suggest, the forms of Wolfson’s poems suit their content well. “The Prayers of Sheep,” for example, experiments with shifting from free verse to prose poem and back again. In the center of the poem, the reader finds herself transported by an unpunctuated, multisensory accumulation of images and sounds:

[……………………………………………….] Burdock immersion mire musing

alfalfa dilemma heat bleat silage psalm listeria weariness escape

mistake ankle debacle pest protest thistle gristle rain malaise

puddle muddle cottonwood canticle abattoir adieu seclusion

tune strawberry aubade dung song. All easily confused. (10-14)

In a different context, it would be difficult to imagine how this particular group of words fits together. In the sheep’s prayer, however, it somehow makes sense that they are “easily confused.”

Above all, these poems are concerned with the act of naming, as the collection’s title indicates. Some poems expose the arbitrariness of this act, for example “Namer of Lakes” (a personal favorite of this reviewer, and not just because it led me down an incredible rabbit hole). Others seek the exact words to get at the specificity of things, whether it be the physical remnants of childbirth in “An Unfunded Study of the Afterbirth,” or the declaration “Ponderous ark: I feel like one” in “My Mother Names Her Inner State” (line 10). This extraordinary precision at first glance highlights the separateness of each individual. A second look, however, reveals the opposite. If we could just get close enough to the thing itself, these poems suggest, we might find it in ourselves and ourselves in it. A Common Name for Everything reveals the hidden ties that link us to something ineffable and universal, a world that is larger than ourselves.

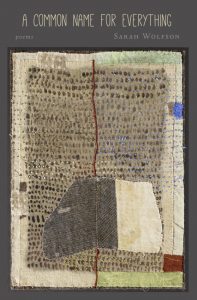

A Common Name for Everything by Sarah Wolfson

Green Writers Press, 2019, $14.95 [paper]

9781950584130 [paper]

Laura Dennis is a college professor in Appalachia. She manages and writes for the Attachment & Trauma Network (ATN) blog. Her nonfiction has been recognized in two literary contests, her writing has been selected as Editor’s Choice for the 2019 Kentucky Philological Review, and she will be the featured author in the Spring 2020 issue of the Bethlehem Writers Roundtable.