Review by Christine E. Salvatore

Review by Christine E. Salvatore

Feminine Rising is a testament to the power of story, how telling a story can be as powerful and healing as hearing one with which we identify. The essays and poems within got me thinking about my childhood. Growing up, my sisters were four years older and twins who never did anything individually, so on weekends Mom would take them on her errands and whatnot, and Dad would take me. It was a good divide and conquer arrangement for parents, and I was more suited for my quiet dad’s activities anyway, happy to read a book or observe the world for hours while we surf-fished on the beach of our hometown. Soon enough, I was dad’s partner in everything, with our own inside jokes and shared opinions on most topics at the dinner table.

That was until I hit puberty. I remember succinctly the day I received a “starter-pack” from Kotex. A girlfriend and I squealed and grabbed the box while my dad laughed and said, “Well let’s open it up! What is it?” As I bolted up to my room with my friend, I heard my mom whisper something to my dad. I glanced over my shoulder and saw a man set adrift, lonely even, as I excluded him from my life for the first time. As my mom followed us up to my bedroom and quietly shut the door behind her, I felt a sense of loss that was not my father’s fault, but my culture’s, maybe, the people who said little girls don’t talk to their dads about this stuff. It took me years to regain some of that closeness with my dad. I suppose we all have our own ‘coming of age stories, in fact, Feminine Rising has a whole section dedicated to the body and sex that begins with a gaggle of stories and poems about first menses, each leading me deeper into thought.

This anthology of poems, stories, and essays by every sort of woman is not only the kind of anthology I would buy to teach one of my literature classes. It’s one I would buy to give to my sisters, my nieces, and women of my mother’s generation, born in the early 40’s, when stories such as these could never be told. Covering themes from “rites of passage” to “sexuality, birth stories, woman as a hero/protector, survival of oppression, and violence,” and so much more; there are life-changing stories here for everyone. Editor Andrea Fekete says, “Sharing story isn’t only introducing legislation or leading a march, but it is transformative of the culture, one individual reader at a time” (xx). These stories and poems are proof of that.

There are seventy-five poems and twenty-three essays, divided into themed sections, such as “On Resistance and Roles,” featuring writing that both inspires and chills. There are good poems here, especially a few by Gina Valdes and a three-poem series by Michelle K. Johnson Huffman. The essays blew me away, made me cringe and nod yes, yes again and again. These stories are so well-written that I would have happily read a novel-length version. Standouts for me included “Ice Fight” by Ann Pancake and Meridian Johnson’s “Somewhere with Cows” (97).

In “Ice Fight,” Pancake tells a story about a brother and sister growing up and unwittingly defying gender stereotypes. The writing is imagery-rich and lyrical, describing childhood in a large family with a silent Reverend father and a mother trying to keep the fighting among her five children to a minimum. The two oldest children, the speaker and her brother Sam, fend for themselves in a world that rejects Sam’s effeminate nature and occasionally nitpicks the speaker’s tomboyish ways the older she gets. The line that spoke a truth that rang truer to me than anything I’d read in a long time was this.

The culture in which we grow up grants far more leeway for expressing oneself as a woman than it does for expressing oneself as a man, while at first thought it seems strange given the sexism of the place, on second, it makes sense: if everything male is superior, why wouldn’t a masculine woman be more acceptable than a feminine man? (Pancake 30).

Truths like these ring out from many of the pages of this absorbing anthology. I’m left thinking about the final line of a striking poem by Gail C. DiMaggio about wearing make-up that suggests there is confusion, betrayal, and evil lurking within the cultural dynamics of gender, but… who is to blame, exactly, when we have bought into these myths ourselves?

The mirror-face lifts her chin, smiles. Promises

I will live

in a casket of ivory beige, and be

her good girl.

She will love me

for telling their lies and never again

my own. The face in the mirror

has blank, black eyes, a hooked beak, a predator’s

sneer. It looks like me.

Someone is a monster (175).

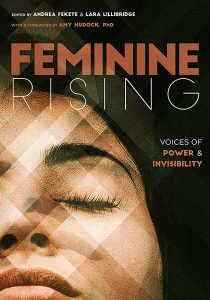

Feminine Rising: Voices of Power & Invisibility

Andrea Fekete & Lara Lillibridge, Eds

Cynren Press, 2019, $28 [paper]

ISBN 9781947976085

Christine E. Salvatore received an MFA from The University of New Orleans where she taught in its undergraduate college as well as at Tulane University. She is a thesis advisor in the MFA Program at Rutgers University-Camden, and teaches literature and writing in the MFA Program at Rosemont College, Stockton University and at a public high school in South Jersey. Her poetry has appeared in many journals including The Cortland Review, Diode, The Literary Review, Mead Journal, The Southeast Review and elsewhere. Her work is also included in the craft book More Challenges for the Delusional and is featured in the upcoming art book, Mother Monument by Holly Trostle Brigham and Maryanne Miller. Learn more at www.christinesalvatore.com.