Author’s Note –

Sarah Cannon On Writing The Shame of Losing

I wrote the memoir The Shame of Losing while I was falling out of love with my spouse. I fell out of love with him for many reasons – not simply because of the brain trauma that changed him. I wish it were that easy. It’s more like the shame of facing an on-going trauma – a terrible accident, rehab, work and financial struggles – changed me and I couldn’t go back to being who I thought I was. My world view exploded. It felt like a fall from grace, even if I know better to understand that it was not.

The aftermath of a near-fatality was a lot of shock and denial by all. There was hope, too. I learned that after hope comes living with ambiguity which sometimes begets a sense of despair. You learn, and for me this was at a ripe age of young motherhood, that recovery is not like the movies. The truth is, not a lot people – not surgeons, not work colleagues, nor insurance bureaucrats – are equipped to handle the unknown. Sometimes even friends and family want to help, but don’t know how. This makes one lonely.

The kids, so young when he almost died, barely tweens as I was writing the book, then full-blown teens when it was published, were the light. With kids, you simply can’t afford to sleep, drink, or cry all day. (Not all day.) You look at them and see their beauty and shake your head when the deepening hole in your heart moans at you that it’s all your fault. You write and play and launder and drive and read your way out of letting that dark place try to convince you that you are not enough.

My story – what happened to us, all of us – is so dramatic and absurd that I used to find myself apologizing for it. He’s ok, really. We will all be fine. The kids are great. Capturing the arc of a young, privileged woman in love with her chosen capable man who goes on to face hardship she never could have imagined, has been the hardest and most rewarding way to contain this grief. Am I still sad? Yes, sometimes. Am I ashamed? Not really. Or I am, but I am working on it. In creating literature and making a book, I found a way to liberate myself little bit. I documented how I viewed the world and I did this for my children.

Excerpt from The Shame of Losing:

My mom lectured me on how the kids needed me at dinner and for bedtime and that Matt was in good hands at the hospital.

“OK, I’ll take them,” I told her, grabbing my coat. “But you’re coming with.”

We left Isaac with my dad. He could feed him hotdogs and peas. I gathered up a blanket and buckled Lizzie in. Lizzie wore her My Little Pony pajamas and we listened to Jack Johnson sing a song about recycling. I could see in my periphery how my mom was folding and unfolding her hands on her lap. We parked in the underground garage. It was dark and cold and I had an idea.

I told Lizzie, “Daddy is sleeping because it’s nighttime. I’m going to give Gamma these few things for Daddy and you and Mimi can stay here, OK?” She nodded, like it was the simplest thing.

Walking toward the entrance, I marveled over the raw honesty of children. It seemed she was OK with the plan because somehow she knew it was a first step—like my responding to her request meant everything would be fine. I squirted antibacterial gel into my palm at the first desk I came to. That scent, the cold, clear gel liquid, has forever seeped into my conscious; every time I use it or smell it on someone else, I think not of hospitals directly, but of emergency vehicles, or intracranial pressure monitors, or the clank of metal wheels rolling portable beds with patients down the hall.

I took the elevator to floor three. I kissed his cheek and rearranged his hospital bed pillow. He was mute, his black- ened eyes glued shut with crusted pus. The crook of his arm where he’d been poked for IVs was yellowing. This had to be a quick trip. Joanna was somewhere, maybe getting coffee in the basement cafeteria. I didn’t text her. Sometimes, I didn’t want an update from his mother, upbeat as she always tried to be. I’d see her later anyways, at my parents’ house where she was also staying. I took the gift Matt’s cousin had deliv- ered and made my way to the elevator.

“Here,” I said, giving Lizzie the white teddy bear. “Daddy wants you to have this.”

Lizzie nestled into the white stuffed bear. It came with a felt rose and a chocolate bar. She snuggled under her cozy blanket and fell asleep on the way home.

A week or so later I would take them both to see him in his new room post-surgery. One of his eyelids was opened a crack and the IVs had been removed. We grown-ups were all saying how great he looked, how wonderful he was re- covering, but that was amongst ourselves, his witnesses and cheerleaders. I can’t imagine the shock it must have been for the small children. Lizzie went to reach for her daddy’s hand and Isaac stayed on my lap sucking his shirt. Children this age do not ask detailed questions, or ours didn’t. Matt wasn’t saying much and we didn’t stay long.

The message was simple: he is ill, but he is healing.

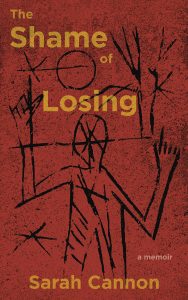

The Shame of Losing by Sarah Cannon

Red Hen Press (November 13, 2018), 160 pages, paper.

ISBN 978-1597096249

Sarah Cannon is the author of the memoir The Shame of Losing. She earned her MFA from Goddard College and has written for the New York Times, Salon.com, and elsewhere. She lives with her two teenagers in the lovely beach town of Edmonds, WA, and works as an administrative professional at Seattle University. She is thrilled to be teaching an online course this summer with Creative Nonfiction magazine called The Zen of Process. She doesn’t tweet but she loves Instagram, and can be found @sarahmecannon.