Review by Kerry Neville

Review by Kerry Neville

An autobiography purports to be chronological account of a person’s life, a progressive recounting of the accumulation of cause and effect events. A memoir, however, is not a recounting but more of an accounting, a clear-eyed, introspective examination of significant (large and small) moments of the author’s life that, when gathered together in narrative, create meaning threaded through time. In short: an autobiography is the straight running stitch, while a memoir is the longitudinal and transverse warp and weft. Similarly, Ana Castillo’s memoir, Black Dove, is less a linear reckoning of the self over time and more a weaving of intergenerational stories, a crossing and recrossing of borders between the United States and México, between brown and white, between women and men, between mother and son, and between independence and interdependence. As she tells us in the opening paragraph:

Perhaps some of you may come away from this book feeling that my stories have nothing to do with your lives. You may find the interest I’ve had in my ancestors as they were shaped by the politics of their times, irrelevant to your own history. My story, as a brown, bisexual, strapped writer and mother, constantly scrambling to take care of my work and my child, might be similarly inconsequential. However, I beg you indulgence and a bit of faith to believe that maybe on the big Scrabble board of life we will eventually cross ways and make sense to each other. (1)

This “making sense to each other” is, indeed, the object lesson of memoir, of listening to each other’s stories: I hear you and you hear me, and in the listening and the sharing we begin to see ourselves in each other and cross borders in this work, inhabiting each other in empathetic, body-swapping transmigration. Castillo asks us to undertake a “radical curiosity” (2) as we move with her through her and her family’s stories of immigration, social injustice, incarceration, poverty, and violence, but also through stories of community, motherhood, solidarity, resilience, and love. Castillo tells us that her mother called her “Ana del Aire,” after a popular telenovela, and says

Woman of the air, not earthbound, not rooted to one place—not to Mexico where Mama’s mother died, not to Chicago where I was born and where my mother passed away on a dialysis machine, not to New Mexico where I made a home for my son and later, alone for myself—but to everywhere at once. (25)

Likewise, Castillo’s stories are of the air, not rooted in one place, and are to everywhere at once.

Castillo renders the difficult moments of her family’s history with compassion but is unsparing in her exacting recollections. In her telling, she moves between two approaches inherited from her tía Flora, mother of five, grandmother of eighteen, and great-grandmother to nine, a woman who left Mexico at seventeen for Chicago. Castillo recounts her Aunt Flora telling her that she “loved” all the years she worked as a seamstress at an upholstery company, but the word her aunt used was “encantada,” which means in English, “enchanted” (28). Castillo remarks that this could not be the feeling her aunt could have meant in describing her factory labors, and yet, isn’t this, too, the oxymoronic feeling Castillo must have in recounting the difficult labors of her family in immigrating to the United States, the difficult labors of being a Chicano bisexual in a patriarchal culture, the difficult labors asked of a single mother who must contend with her son’s addiction and incarceration but is, as a writer, enchanted by the telling? And it is her Aunt Flora who, in response to her mother’s concerns that Castillo “might or could write about our family,” gives tacit permission to her niece to write the truth, saying, “I don’t care if she writes about me. She’ll make me immortal” (35).

While her Aunt Flora might have been referring to an immortality bestowed upon movie star legends, this is a necessary immortality for people whose stories have been long marginalized or erased by white, Western, patriarchal culture. In the “Introduction” to Black Dove, Castillo states that her memoir is addressed as a “message” to the “the next generation of dreamers.” This is the power of memoir: examining the past to understand how it might be a useful touchstone for the future. In a moment that gathers past, present, and future together, the warp and weft, Castillo writes

I read and write poems. I listen to music, I sing—with the voice of my ancestors from Guanajato who had birds in their throats. I paint with my heart, with acrylics and oils on linen and cotton. On the phone, I talk to my son, to a lover, and with my comadres. I tell a story. I make a sound and leave a mark—as palatable as a prickly pear, more solid than stone. (25)

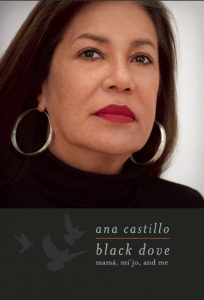

Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me

by Ana Castillo

Feminist Press, 2016, $16.95, [paper]

ISBN 9781558619234

Kerry Neville is the author of two short story collections, Remember to Forget Me and Necessary Lies. Her fiction and essays have appeared in many journals and online magazines such as The Gettysburg Review, Epoch, Arts and Letters, The Washington Post, and The Huffington Post. She is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Georgia College and State University.