Review by Judy Swann

Andrea Potos is obsessed with John Keats, as she says in “Verse Virtual.” So it feels natural to see her cite from his letters in “Morning of my 56th Birthday,” the opening poem of her chapbook Arrows of Light:

The first thing that strikes me on hearing

a misfortune having befalled another is:

Well it cannot be helped — he will have

the pleasure of trying the resources of his spirit (11)

This is how the poet comforts herself and accepts that fact of her mother’s radiation therapy:

…he will aim one perfect

arrow of light in the errant spot that would claim

her if it had its way, my mother

from whose body I came. (11)

This poem is a 14-line poem, but not a sonnet, not even a nonce sonnet. Its shape is 4, 5, 5, with the turn before the last 5. It is perfectly articulated in American plain-speak and as perfectly crafted as anything from Lorine Niedecker’s condensery. It weaves in other voices, as poets have been doing since Pound. Its opening quatrain is a nature poem.

The lake is a blue scarf ironed

by stillness, locust leaves burnt

yellow, everywhere, softness

in September air. (11)

Compare to Keats’s “Blue! ‘Tis the life of heaven”:

Blue! gentle cousin of the forest green,

Married to green in all the sweetest flowers,

Forget-me-not,–the blue-bell,–and, that queen

Of secrecy, the violet…

And in the deft ekphrasis of the second poem in this volume, “The Day Before the Late October Birthday of John Keats,” Potos identifies a book she bought for the beauty of its cover, her Vintage Keats. You’ll recognize it if you search for it online.

…a meadow is pierced like a night

sky of bluebells, a million twilights of blue dreaming,

those same hues as the fabric of her gown . . . (12)

Keats died young—25—and left behind a very small body of astonishing work, a great number of which are poems of some length – “The Eve of St. Agnes,” “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” “Ode to a Nightingale,” “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” and “Lamia”—many of which he produced the year after his brother’s death. If we read Arrows of Light as a long poem growing out of and memorializing Potos’s love for her mother, short poems qua subsequences — as I would argue we should—then we can squeeze some extra sweetness from “For My Friend Who Told Me Don’t Fête the Dead”:

what we have come here for every summer for so long

I can’t tell you when it began, here comes our waitress,

Balancing two plates of blueberry pie plump and crustless, (36)

Keats himself fêted blue, as noted above. But he also fêted gold, most notably in “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” which opens “Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold.” Here is what Potos says in “Gold”:

…It streamed through her yard

where we played in the tickling grass . . .

and we knew it wasn’t white

the angels wore (21)

And again in the closing poem of the collection, “Mom, Leaving”:

For her I imagine

it was just the last page, the one

with margins illuminated, gold

burnished and burning, edges

raggedy and soft to the touch as she (39)

The collection consists of 26 poems in two parts: Part 1, Gold and Part 2, Mother/After. It is a total of 317 lines, about the size of “The Fall of Hyperion.” One of the poems, “I Have No Poems from My Ireland Trip But This One,” received the 2016 William Stafford Prize in Poetry from Rosebud magazine. You can feel the Keats in it, despite the fact that the long-poem format that Keats is most famous for is not a form practiced by Potos, or really by anyone writing in English in these times (the Russians do them, though, and call them поэмы):

We drove alongside bogs and heath, green

deepening to more green, low mists and rain—

seeped stones of the abbey, its gothic church

built for the memory of a mother and wife

gone too soon. (31)

But in the end Potos’s narrator, American in a way Keats could not have been, intimate—even bosom-close—in the way of the great confessionals—Sylvia Plath and Frank Bidart come to mind—identifies Ireland as the place where she got through to her mother for the last time:

Now, months past, Ireland remains

buried in the turf of her leaving,

the peat of my heart

still burning. (31)

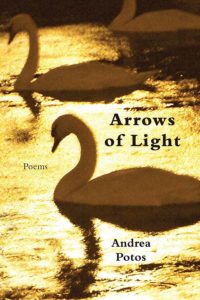

Arrows of Light

by Andrea Potos

Iris Publishing Group: 2017, $12 [paper]

ISBN 9781604545036

Judy Swann is a poet, essayist, editor, and bicycle commuter, whose work has been published in many venues both in print and online. Her book, We Are All Well: The Letters of Nora Hall has given her great joy. She loves. She lives in Ithaca, NY.