Review by Deborah Hauser

Review by Deborah Hauser

Clothesline Religion, Megan Buchanan’s debut collection, is a paean to motherhood, domesticity, and transcendence. The poems flow freely without constraint, sections, or epigraphs. As explained in the “Author’s Note” (which I urge you to read), after trying different methods of organizing the poems, Buchanan discovered that they lined up alphabetically. Her devotion isn’t bound by scripture. She finds “God…everywhere” (54). She is spellbound by “ordinary magic” (49), finds grace in “stacks of white cotton diapers”(3), redemption in the “new slivermooon” (41), and joy in a child’s hair.

The clothesline, and it all evokes, appears frequently, starting with the first poem (the title always makes me smile), “A New and Fervent Domesticity Has Seized Me” (3): “my reverence for clotheslines / has been around for years.” The new mother in this poem is seized or possessed; she can “out-sweep Cinderella.” She is also self-aware enough to question “this pressing of creases in myself…filling up all of my free moments.” The poem takes a marvelous turn, exposing the other side of cleanliness:

as if untidiness was the reason

he didn’t want us

as if

I wasn’t clean (3)

Buchanan has a talent for elevating the quotidian and finding the divine in simple images and gestures. “Almost-Spring In Everyone” (5) celebrates “aspen shimmer brandnew,” “holy breakfasts,” and a baby who leaning “over her father’s shoulder, slowly / raises a hand, anointing me.” The hyphenated “Almost-Spring “and merged “brandnew” are examples of Buchanan’s unique approach to combining familiar words to create fresh language. New phrases such as “Deepdown” (28), “motherforce” (42), or “feverfire” (50) are created by removing the usual space and fusing the words together. The resulting neologism gives each word equal emphasis with a subtle shift in meaning. This is a visual sleight of hand that has to be seen on the page to be appreciated; an audience listening to the poem would simply hear two words.

A mother’s quest for cleanliness re-emerges in “Archetype Study #1: Mother” (6). The poem opens with a list:

Flax meal, omega vites, clean hands,

clean sheets, clean floors, clean

lines of communication. (6)

Notice how Buchanan repeats the word “clean” like a chant and lets it hang at the end of the second line. The poem progresses from clean body (hands), to clean home (sheets and floors) to clean mind (communication). The chore of cleaning becomes a transcendent practice; a ritual that purifies the mother’s body and soul and prepares her to connect with her child.

The clothesline reappears in the closing lines of “Long Weekend Shorts”:

and home’s behind us, home

also waits up ahead: the honey jar,

the clothesline, our books and cats,

the well-made bed. (35)

The poem ends with a list of the things you look forward to coming home to after a trip. The clothesline is unexpected among these items. I read it as a welcome return to the usual routine and, perhaps, a tether that keeps the mother grounded in that routine.

Anxiety about exposure is the theme of “Digging in the Bins” (18). The speaker, a student and mother, is self-conscious as she imagines someone rummaging through her garbage and passing judgment. The contents of her trash become increasingly intimate. The first stanza describes food: “coffee grounds,” “tortilla crusts,” and “broccoli.” The second stanza exhibits her personal papers: “Student loan statements, postcards,” and New Yorker renewal squares.” Finally, “a small sheaf of poems” and her sex life are laid bare: “she’s in bed…She’s naked in this one!” The poet who writes first person narrative poetry must negotiate a delicate balance. The reader should thrill to imagine she’s getting a glimpse of the poet’s inner life on the page without the poet wincing at having revealed too much of herself in her work.

“Naked Lady” (39) reads like an inventive portrait: “my kind of girl…at the edge of town, most obscenely / and courageously leaning naked…” There is separation between the “lady” described and the speaker who envies the flower’s brazen nakedness “beneath my California clotheslines.” In this context, the clothesline suggests a kind of exposure; even clean laundry on the line reveals something private to the world.

The clothesline is communal gathering place for women; a place of intimacy where dirty laundry is aired and secrets are revealed. Hanging laundry out to dry is also physical labor. The women portrayed here work hard, but never lose their capacity for joy. Buchanan’s poems will make you a true believer.

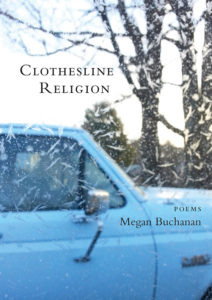

Clothesline Religion

by Megan Buchanan

Green Writers Press, 2017, $14.95, [paper]

ISBN 9780996897396

59 pp

Deborah Hauser is the author of Ennui: From the Diagnostic and Statistical Field Guide of Feminine Disorders. Her poetry has appeared in Bellevue Literary Review, TAB: The Journal of Poetry & Poetics, Carve Magazine, and Antiphon.