Reviewed by Libby Maxey

Reviewed by Libby Maxey

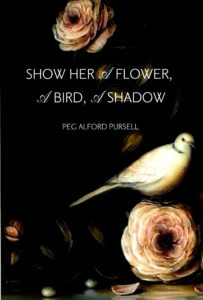

At seventy pages, Show Her a Flower, a Bird, a Shadow is too long to be a chapbook, but it has that feel: focused, intimate, slight yet substantial. Peg Alford Pursell’s stories tend toward poetic microfiction; most of them could fit on a single page, although this edition gives them ample breathing room. And they do breathe, swelling and contracting through each living, human moment. “The breath is the breath is the breath” (3), as we’re told at the end of the first story (“Day of the Dead”), and that sounds like an invitation to connect, viscerally, not only with the dead, but with the fictional, too—with anyone that writing makes real.

Pursell, whose work has been shortlisted for the Flannery O’Connor Award, is the founder of a national reading series, Why There Are Words, along with a young small press of the same name. Whether on the page or in person, she is dedicated to making a place for other writers’ voices. In her own book, the voices she amplifies are those of variously abused children, parents struggling to understand what their children need, and lovers struggling to exist in relationships where they don’t fit—or to accept the loss of relationships that let them experience belonging, however temporary or illusory. In “Human Movement,” Pursell captures the disorientation and sense of impossibility that a woman faces as she awaits her mother’s impending death. In “Nora and Paul at The Coffeshop,” she teases out two sides of a woman’s anxiety—the fear of being unseen and the fear of being seen—while illuminating the complexity of blame.

Pursell also touches on the complexity of storytelling, which is never a straightforward transaction. “Fragmentation,” a favorite of mine, is a paragraph-long window into the mind of a girl (or woman?) whose aversion to a particular story is the same as her identification with it. “She hated the story about how the old fisherman cut up the sea stars, throwing each arm into the sea—” (37) but in the end, she takes her own fragmented, healing self to the bathroom for water. In “My Descent,” my favorite piece in the collection, Pursell speeds us through the wild and giddy stream of consciousness of a hiker losing her footing on a snowy mountainside. The comic, downhill slope of associations, from choir teacher to margarine to Heidi’s red skirt, bottoms out in heavy contemplation of our isolation in the world. Seeing the fair-trade, Tibetan rainbow patch on her parka, the speaker thinks,

Clothing…will not save us. Facsimiles of scientific phenomena sutured to cloth, carried to the grave, to tell someone a tale. I’m going down, Heidi here in my heart, the Tibetan’s care radiating from over it like a flag. Girls who are with me for no reason that I can say. And without the understanding, perhaps I am alone. You will say I was alone. (55)

Although these final thoughts suggest the limitations of art, the exhilarating and engrossing narrative undercuts the cynicism of the doomed. As readers, we go right down the mountain with her (and Heidi, and the Tibetan girl).

Pursell’s stories are most powerful when they take us somewhere unexpected, but even the simplest of them excites sympathy. We feel for the woman in “A Worn Sock” who can’t find time to deal with her worn-out marriage: “The sensation would either worsen as she went or she would grow numb to it. She didn’t want to stop to change” (39). But we also feel for the man in “Cherished,” whose holey sock is a different kind of metaphor. His handmade socks are a reminder of a lost love, and the hole in the toe is proof of an imperfection that he never suspected in her; but the hole is also a symbol of freedom and an opening for a new relationship. While he waits for someone new, the socks are something that he can truly love. There’s a similar touch of hopeful coziness in the way “U+2204” ends: two people with nothing, each taking shelter from the rain at a bus stop, settle into mutual understanding, even though neither is telling the other the truth. In this debut collection, Pursell’s honesty encompasses not only the truths that aren’t told, but the ones that can’t be known, and yet touch our lives all the same.

Show Her a Flower, a Bird, a Shadow

by Peg Alford Pursell

ELJ Editions, 2017, $16.99 [paperback]

ISBN 9781942004288

Libby Maxey is a senior editor with the online journal Literary Mama, and her writing has appeared in Mezzo Cammin, Crannóg, Think, and elsewhere. She reviews for Solstice as well as The Mom Egg Review. Her nonliterary activities include singing classical repertoire and mothering two sons.