Review by Zara Raab

Review by Zara Raab

– Levi’s earlier books, Once I Gazed at You in Wonder, winner of the 1998 Walt Whitman Award, and Skyspeak (2005), give a large place to relationships: to a mother whose death she grieves and a father who stirs the strong admixture of anger and love on the palette of many second wave feminists. In Levi’s new book, Orphan, the subjects and significant others of her imaginative world have shifted to contemporaries or near-contemporaries, husband or admired poets. Orphan’s best poems give embodiment to the splicing of pain and love––what Alice Fulton reviewing Levi’s earlier work called “the unbidden, bereft emotions in between [grief and love]: the unnamed imbrications that constitute the affective life”––through her marriage to an unnamed “adventurer,” bound to his wheelchair by biology gone awry and to the poet-his-wife by love.

“Reading Robert Lowell’s ‘Skunk Hour’ in the 1970s,” the first poem of this powerful series, seems to take us off the scent, only to reveal its relevance brilliantly by the section’s end. Describing the handsome, blue-eyed male students in the class who emulated Robert Lowell, epitome of wishful thinking, she admits:

I wanted to be with the boys so badly,

watching the red fox stain cover Blue Hill.

But even then I knew I was the fox and I was the stain.

By the end of this series, we understand that in the poet’s terms how she is the fox hounded by her instinct for love. Here is her poem “What Love Is” in its entirety.

To forsake all others.

To flat the beloved on your back

from flood to land, to wrench bread

from the beggar’s hand, snatch

the oxygen mask from a child’s face.

To ransack hospitals and nursing homes

for drugs to ease the beloved’s pain,

to stumble down 1010 floors, beloved

slung on your back, not stopping

for the other ones in wheelchairs

waiting at the landing doors.

Levi understands the costs of love, too. “Another Inventory” tells us:

there is always more to give up

–what we must all give up, though the inventories may vary from person to person, as mortals recognizing our own mortality. This poem is the literary equivalent of the vanitas still life, a sumptuous plate of fruit painted by the Dutch in the 17th Century, with the small skull, piece of rotting fruit or timepiece as reminders of our mortality. Levi’s list includes “the sundial’s gnomon/ the flight of stairs knit with the river//[… ] the smoldering koi leap into the sky’s lap/ the cicadas drop from the trees, exhausted/from a life of singing”. The inventory also includes the very self-sacrifice that such a list implies in the first place—her care-taking role in regard to “The Adventurer” on the book’s Dedication page:

then the walking man—you make him crawl back to his wheelchair

“Because we like the maps” says why the poet and the Adventurer take trips. After telling us, vividly, how the two of them manoeuver his body from the wheelchair into the car, she writes,

Maybe our kiss is a gentle

fuck you to anyone who’s watching

who thinks our life is less than theirs.

Not for one moment does Levi convey the feeling of having been simply abused by fate: that is how clear-eyed she is about herself and her own nature. The power of the work lies in her refusal to evade or avoid the hard truths.

Poems like “Unlucky” do not use much punctuation (except within a line), thus blurring the boundaries between one sentence and the next, between small letter ‘I’ and capital ‘I’, the way boundaries are blurred in intense love. In “That’s the Way to Travel” the poem’s form is clear—unrhymed tercets with line-breaks mostly following standard syntax. In a further departure from free verse, Levi gives us “Three Songs,” each of them metrical and singing: “My mother lost herself to the burning flu. / My father loved her, he went too. “

Another section of this slim volume contains odes to June Jordon, Muriel Rukeyser, Jane Cooper. Entering these poems about women, feminists, poets, writers in a certain time in American history—mostly the 1960s and 1970s, but sometimes earlier––feels like coming into a special club where the women know each other and can be fully understood only in terms of each other.

Alice said she was a pine, and sometimes I think

she got tangled in her own branches. [. . . ]

[ . . . ] there were poems she’d already written,

and if not Muriel’s speed of darkness,

they had the shine of silence.

There is a new restraint in Levi’s work compared to the lush narratives of earlier volumes, as if this poet, too, sought “the shine of silence.” Elsewhere her she is longing to “turn back the time on the clock of love//find you/ have you take my silence in your hand/ your hand, five-petal rose”. Within the poetic framework Levi has set for herself–-the exploration of intimate and literary ties rather than, say, the embodiment of landscape through emotion nuanced by distance–– Levi’s words in Orphan emit a heightened and powerful fragrance.

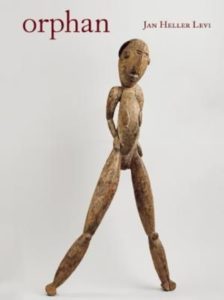

Orphan

by Jan Heller Levi

Farmington, ME: Alice James Books, 2014

Paper, 62 pages, $15.95

Zara Raab’s latest book is Fracas & Asylum. Earlier books are Swimming the Eel and The Book of Gretel, narrative poems of the remote Lost Coast of Northern California in an earlier time. Her poems appear in River Styx, West Branch, Arts & Letters, Crab Orchard Review, and The Dark Horse. She is a contributing editor to Poetry Flash and The Redwood Coast Review. Rumpelstiltskin, or What’s in a Name? was a finalist for the Dana Award. She lives near the San Francisco Bay.