Review by Judy Swann

– Women are constantly tempted to measure reality in terms of the measurements of Father Time, which are linear, clocked. This is a trap. Our gynocentric time/space is not measurable, bargainable. It is qualitative, not quantitative.–Mary Daly (Gyn/Ecology 41)

In The Kingdom Where No One Keeps Time, Helen Ruggieri manages to lift time from the prisons of chronology and ethnicity, and she does so with bravura. The opening three poems, a cycle called “The Fates,” can be read again and again with never-diminishing pleasure. The Greek poet Hesiod was the first to write about the Fates. According to him, they were either daughters of the Night or daughters of Zeus (Father Time himself), thus the ambiguity among classicists about whether the Fates were superior to the gods or subject to them. Neither Hesiod nor Ruggieri, however, deny their elemental power; and Ruggieri’s meditation on the Fates makes what Hesiod has to say more or less beside the point.

In “Clothia: Threads the Needle,” the title, with its verb clause, uses asyndeton to bleed into the first line “wearing her blue wrapper” (5). Is she Nut the Egyptian sky goddesss? Her wrapper is “embroidered with a gold dragon”—is this an annexation of Ruggieri’s Japan studies? Perhaps. But next we read that she is

looking out on a field of poppies

peels potatoes,

quarters them

into a cast iron pot. (5)

Morpheus, the god whose symbol is the poppy, is also a child of Night. He is Clothia’s brother. The poppy’s heavy red flowerhead is laden with dreams, poetry (ask Shelley!), and fantasies. Here Clothia looks out at a field of poppies. Subject to them or superior? Their equal? The incarnation of a symbol? All of the above?

In any case, her needle is not yet threaded when Crow—a Native American avatar of intelligence—arrives:

a long red thread in his beak

trailing like a spittle of blood.

She winds it on a wooden spool, (5)

The poem closes with an image of dawn:

…one spot

by the inlet that catches the sun,

opens wide as a golden eye. (5)

The opening stylistics of the cycle’s next poem ties it to the first: it too has a verbal clause in the title that flows into line 1 of the poem, again without a conjunction:

Lachesis: Makes the Stitches

steps to the light,

drifts from where she

was sired by Dark, (6)

What are the stitches of poetry if not the sounds of our mouths and tongues? Read this next stanza out loud. Listen to its rich labials sizzle against the fiery liquids and the guttural:

embroiders a serpent

in red on a purple gown,

eyes of fire opal, (6)

We don’t just see Clothia’s sister, we hear her, even though she is still “about to speak.” Her language is not mundane, not like ours: it can’t be, because of how she’s built:

tongue ending in a peony (6)

It sounds like a category mistake or a Frida Kahlo painting, but it might just be some other painterly language I have not yet studied. She is still in the kitchen. She “stirs the stew.” But she’s also working on that embroidery. We read that her needles, oddly, are pewter. Is she sewing a poison right into life? The pewter’s lead lades her needles with meaning. Yes, we carry our death with us, yes it is part of the fabric.

The poem closes with an image of the sky of broad daylight:

The nacreous sky opens an eye

of turquoise (6)

Now we come to “Atropos: Cuts the Thread.” Here, the pattern is broken. The title stands apart from the body:

How beautiful the serpent’s tongue,

she thinks and, judging done-ness,

dishes out the stew. (7)

It is a single day, that’s all. Time to eat. Then a little reading before bedtime:

She reads their poetries

wrapped in a black robe,

cobwebs traced in silver on the sleeves, (7)

The poem closes with an image of the moon against what seems to be a line from the I Ching:

Above, dark wings of kohl

steadfast against titanium.

There is no wavering. (7)

No imagist could have said it better.

And there are another 50 poems in the book! I recommend them all—the poems about funerals and nursing homes as well as the poems about the natural world, especially the Allegheny River poems. Read them slowly.

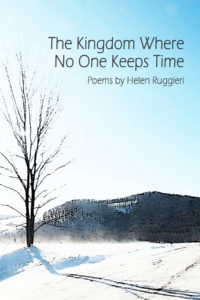

The Kingdom Where No One Keeps Time

by Helen Ruggieri

Mayapple Press, 2015, $15.95 [paper]

ISBN 9781936419555

Judith Swann’s poetry has appeared in Mom Egg Review and in many other venues, both in print and online. Her edition of the letters of Nora Hall, We Are All Well, appeared in hardcover in 2015. She lives in Ithaca, NY, where she is trying to foment an e-bike revolution.