Review by Issa M. Lewis

Review by Issa M. Lewis

– The complexity of motherhood is often overlooked; we are frequently urged to consider only sentimental images of manicured women playing with their remarkably well-mannered infants on white sofas. While joy is certainly a significant piece of the experience, the title of this poetry collection reminds us that it is not the only one. In The Dead in Daylight, Melody S. Gee skillfully demonstrates that to become a mother is a complicated process of both creation and loss, and it ushers the living into the process of dying—literally darkness to light and back again.

The birth process itself marks the beginning of the dichotomy. For example, in the poem “Go Back, Make Ready”

Another girl and we are four.

She, too, cut from the opening sharp

but not straight,

the same one closed two years before.

We know only two things:

damage and repair.

…

Her little gleaming body has never

harmed anything, yet I am

a throbbing tear, a swollen scar,

an evacuated ballroom.

She has not done this to me.

And yet what did. (31-32)

Childbirth both enriches and damages the mother. The title of the poem refers to other lines from within it that read “Repair is made from go back / and make ready” (32), addressing the idea that to heal from childbirth is to return to a prior state of being, a time before motherhood—however, Gee’s point, in this poem and throughout the book, is that this is not truly possible. Childbirth is permanent alteration, both beautiful and terrible in its scope.

However, motherhood is not limited to biology in Gee’s book. Several poems refer to the speaker’s adopted mother and the tension that exists in their relationship, in part, it seems, because of the mother’s infertility and the speaker’s ability to bear children. Much has already been said socially about our society’s expectation of women to bring children into the world; naturally, this could cause an infertile woman to feel as though she is lacking. However, one rarely considers that those feelings of resentment might carry through to an adopted child. Gee deftly addresses this in “Why We Are This Way”:

Because she came by both with her own mother,

now immigration is the only thing she knows of mothers and daughters.

…

Because now my hips are crooked, my belly

soft and rippled from the girl

I carried, I have done yet another thing she could never.

Because I speak and she speaks and neither can listen

in the other language or silence our own because,

without words, what would we then have to know? (20)

Gee references these contrasts with beautiful imagery and anaphora. Her figurative language takes unexpected turns, never veering into the sentimental, but loving just the same. For example, in “A House of Paper and Gut,” she writes

I have neither honeycomb

nor nest. There is nothing of

my feathers in your bed.

I am not the burrowing animal

who claws a home, who chews

and tacks it together with her tongue.

I cannot bring from myself a house

of paper and gut.

You will come with much already

built, already to be torn down.

But we are not builders.

Look how we have made

you without any hands at all. (5)

In this way, Gee’s voice is vital, emotional, and raw throughout the book. It speaks to women who understand that motherhood, with all of its mythos, is rarely the simplistic bliss that we are taught it will be. It is instead multifaceted, intricate, and lays bare both the best and worst of us as human women. The Dead in Daylight, in fact, reminds us that both light and darkness are necessary to the experience of motherhood and should be honestly recognized as such.

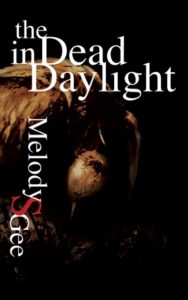

The Dead in Daylight

by Melody S. Gee

Cooper Dillon Books, 2016, $14.00 [paper]

ISBN 9781943899012

55 pp

Issa M. Lewis holds an MFA in Poetry from New England College and teaches composition and professional writing at Davenport University. Her poems have appeared in publications such as Blue Lyra Review, Jabberwock, Mom Egg, and Tule Review. She lives in southwest Michigan with her husband and two sons