Reviewed by RZ Wiggins

Reviewed by RZ Wiggins

Anyone who has been in a cross-cultural relationship will empathize with the frequent cultural misunderstandings and the awkwardness of family and friends who don’t speak the same language that are prominent in Tracy Slater’s memoir. The book is testament that such obstacles can be overcome.

Slater meets her husband-to-be, Toru, when in her late thirties, an independent, Ph.D. professional. Reluctant to relocate from her native Boston, she declares herself “bicontinental,” maintains her apartment, commutes to her job teaching MBAs to write, and develops a literary series sited in Boston and Tokyo.

Japanese can be reserved towards foreigners. Even assimilated non-Japanese who have lived in the country for years can feel that there is a barrier keeping them on the fringe. As one expat friend laments to Slater, “Japanese people are constantly reacting to you like you’re some kind of bizarre alien.”

No surprise that when in Osaka Slater lives a “half-life” spending most of her days alone in an apartment with rooms the size of closets while Toru works the long hours demanded by Japanese corporate culture. She is reduced to not being able to converse with the neighbors, order lunch, or give a taxi driver directions, and is understandably conflicted:

“I just didn’t want to make a decision I was supposed to be sure about forever. I felt trapped, not by Toru, but rather by Japan. Like the country was a prison I could never fully escape if I married someone who called it his home. Our home.”

Connecting to the expat community, freelance work, and finally, learning the language helps her adjust. Eventually, there are fewer Boston trips and a marriage. Slater succumbs not to a place, but to her husband’s pragmatic and comforting love.

“Nothing had ever made me feel as safe and loved as Toru navigating me though an entire world both fascinating and impenetrable. I knew I would love him no matter where we were. . .If I was trapped by this country, it was a trap of my own construction.”

Slater’s great concern about surrendering her “meticulously cultivated life” to become a shufu (housewife)—as 70% of educated Japanese women do, compared to 30% in America—causes her to underestimate what she might gain. For this she can be forgiven. So acrimonious is the “working woman vs. wife and mother” rivalry in America that it doesn’t occur to her that this dynamic might be very different in Japan, or that she might react to it differently.

And as many highly educated persons are apt to do, Slater eventually finds her home in Osaka with Toru not through intentionality, but through the simple act of being there and of melding into its familiarity, and into their rhythms together in that place. She assumes the traditional Japanese role of caring for her father-in-law and doesn’t falter when he becomes fatally ill. Love for him and his son, her new family, a more cohesive and caring unit than her birth family, is evident in her every act.

Slater’s writing is not particularly lyrical, but it is honest. And it is most poignant in the latter part of the book when she, at 41, and Toru try to conceive. Her descriptions of failed IVF attempts and miscarriages, the rejection of adoption as an option, the anger at circumstance, will ring true for many:

“I knew there was no reason, no redemptive message, in our not being able to have a child. I had no patience for anyone’s well-intentioned efforts to push a silver lining my way. . . Instead of redemption or meaning, what you have to find in the trail of years of failures, I was coming to believe, is the determination to go beyond those failures. To build a full and meaningful life not because of but in spite of them. When friends or family talked about “gestating” a book or any other opportunity instead of a baby, I gritted my teeth. I counted their children in my bitter brain.”

Shortly after her father-in-law’s death Slater, at 46, delivers baby Elli. The reader is glad that Slater’s story has a happy ending, but it is almost unnecessary. By the end of The Good Shufu, Slater has evolved from a self-absorbed adventurer into a mature, grounded and calmer woman capable of much nurturing, just what an infant needs on any continent.

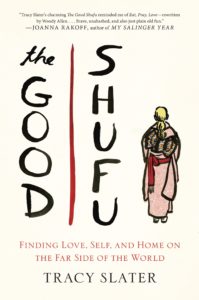

The Good Shufu by Tracy Slater

G. P. Putnam’s Sons 2015

323 pages, Hardcover

RZ Wiggins is a reformed lawyer who has been writing since she was a wee child. She is working on a collection of memoirs about experiencing 9/11 from outside NYC and WDC and her first novel. She works as a Project Editor at the Yale School of Management.