Review by Jennifer Martelli

Review by Jennifer Martelli

– From the opening title poem where we are told, “Never mind what your mother says” (3) to the closing poem “Chained Reaction” where Betts writes

The top of my mother’s hand

is tan shallot skinand her shelter

a crosshatched clam,

a sealed mouth

hiding sealed hands (64-66)

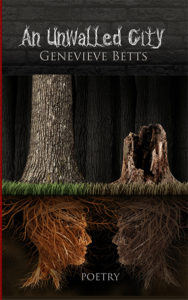

Genevieve Betts creates a seismic movement across a continent, a country, a body in her debut collection, An Unwalled City. The reader is in “this limbo” where “flows blood from the breasts that give suck” (“Isis” 14-16). In the thirty-eight poems that make up this collection, Betts births and unearths pulpy fruits, violence, and arachnids that bleed, drip and crawl across her landscape.

Betts maneuvers the travelling seamlessly, allowing these images to organically sprout throughout the book, throughout time, and throughout place. An Unwalled City is written in two sections, the first devoted to the birth of the poet’s son, and the second to her own childhood in Arizona, her heritage, and her move to New York. Describing the birth of her son in “Geneses,” Betts writes, “I thought he would begin/like a low-hanging fruit–fleshy and plump” (4-5). The fruit in “Stealing Fruit” where “We move from one portal/to another–” is the fruit she and her brother steal from a different time: “My brother and I pluck…like we did picking oranges” (30-32). Finally, across the United States, in New York, she writes of food with “the taste of someone else’s hunger” (“Yen” 54-57). The prickly lushness of Arizona is replaced with the old, cold stability of New York.

I was fascinated by Betts’ insidious images of violence that become deadly and real in the second half of the book. Listen to the gorgeous myth/dream of the pelicans in “Maternity”:

They thought they saw

mother birds plunge sharp beaks

into their own breasts, bleed

feed their flesh to the babies. (6)

In “Kin,” a husband doesn’t like the picture of his great grandfather: “It looks like there’s a demon underneath” (“Kin” 17). But the bleeding wounded move out of myth and into Betts’ reality in the poems “Next Door” and “Bagdad, AZ.” Both poems describe guns in the hands of men: “All concrete walls in our building/so we heard nothing./We didn’t know that he was shooting her/over and over” (“Next Door” 58). “As if violence followed her, a bullet from the gun of the suicidal neighbor next door in Arizona “grazed my crib/inches from my peach-soft face” (“Bagdad, AZ” 63).”The child’s crib is planted in coffee-cans, “a trap for Bedouin scorpions.”

The arachnids—those leggy roamers—are a constant image in An Unwalled City. Betts describes her son: “his corner eyelashes/resemble thin spider legs….and they remind me/of the Daddy Longlegs” (“Swim Lessons” 10). I think a spider, with its strong and silky strands, is the perfect creature to encase the breadth of Betts’ poems: the webs can be invisible, yet deadly. Betts clearly has an affection for these creatures, which she identifies as female. As she states, “We are not a family of spider killers” (“Release” 38-39); the spiders of her Arizona youth are admired and identified with:

The spider emerges, a large tarantula

with the rust-colored dust of Sonora

still striped down her back.

She is cautious of this new land: (“Captivity” 36)

In the East, though, the spider becomes an image for loneliness, for other-ness. Walking the snowy streets of New York, Betts sees

a toddler’s shoe standing

alone on a stoop,

a broken umbrella,

its silver spines reaching

up to the sky

like a dead spider. (“After the Snowstorm” 59)

Pulpy fruit, blood and breast milk, spiders and foods with sugar webs are all strung together in a “necklace” to hang from the body of a country. With the same genius that moved Sylvia Plath to envelop her masterpiece Ariel with love images, Betts envelops An Unwalled City with fragile “white velvet” mother images. The power of this collection is how the poems within contain complexity of “saguaro arms blooming violet stars/from the wax of cactus skin” (“Weaver’s Needle” 52-53)” and demand that we enter. Genevieve Betts’ poems in An Unwalled City are patient, don’t fool around; they wait like her hungry spider until “A fierce flash and her fangs//sink deep into cricket meat” (“House Pet” 37).”

An Unwalled City

by Genevieve Betts

Prolific Press, 2015, $14.95 [Paper]

ISBN 9781632750167

66 pp

Jennifer Martelli is the author of The Uncanny Valley (2016, Big Table Publishing Company). She is a recipient of the Massachusetts Cultural Council Grant for Poetry and is an associate editor for The Compassion Project.