Review by Emily Webber

Review by Emily Webber

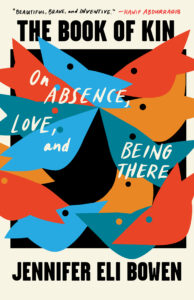

Jennifer Eli Bowen’s memoir in essays, The Book of Kin: On Absence, Love, and Being There, covers twenty years, exploring topics such as marriage, motherhood, the transformative power of writing, and different kinds of communities—when they succeed and when they fail us. Whether Bowen is analyzing her own personal experiences, like her disintegrating marriage, or examining how prison systems operate, she shows the reader how people learn to care for each other and how sometimes we fall short.

In the opening essay, Bowen recounts being at her father’s funeral, a man who chose to stay absent from her life. She tries to piece together her father’s story and create a narrative to understand why he never contacted her and her siblings. When she begins teaching writing classes in prison, she doesn’t yet realize her father also served time, though not as extensively as many of her students. However, she knows it happened “during the worst time in his life” and that it “severed him from human connection exactly when he needed it most.” She explains how these fears can be passed down through generations—woven into what we inherit from those who came before us.

Bowen, founder of the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop, writes extensively about the prison systems in America and Norway in essays that are alarming, heartbreaking, and revealing. American prisons are places where all human rights and dignity are stripped away, places where a lack of care and community persists, and Bowen shows how that harms individuals and society. Even if someone is lucky enough to get out, there is no getting away. “An incarcerated friend of mine says you serve a life sentence regardless of how many years you live in prison because you will never shake the shame of doing time and no one on the outside will forget it either.” In contrast, she visits prisons in Norway where the focus is on healing and rehabilitative care.

“Blueprint” is an essay in a series of “case studies” on how people learn to care and show love through their interactions with others and through observation. This essay blends together Bowen’s childhood relationship with her mother and her experiences raising her sons. She examines these periods in her life and what she observes from others to try to get it right. But in the end, is being correct all the time what truly matters? No, because we won’t be, but what we know for sure is we need love and care to be present.

I like to believe love works a little like that pluripotent cell. Apply anywhere, even a little or haphazardly, and because our lives depend on it, we can make something functional, if not downright beautiful out of it. Growing well, despite the wound.

In a more lighthearted view of community in “The Library,” Bowen explains how the small free library she sets up outside her home encourages unexpected interactions, such as anonymous conversations in a blank notebook left in the library, filled by various people. But it also highlights the small ways people can disappoint each other. Bowen describes watching a little girl who comes to the library for weeks, looking for picture books. However, Bowen doesn’t want to part with any of her books for sentimental reasons, even though her sons are now older. When there is finally something in the library for the girl, she has already given up and stopped coming. It’s a missed opportunity to connect and make a person feel cared for. Even when we have the best intentions, we sometimes get in our own way.

In some of the essays, Bowen describes caring for animals and her hobby of raising chickens, revealing how, even when conditions aren’t ideal, animals and humans are fragile but resilient, which means there’s a chance—even if we don’t get it right the first time—to try again with each other.

If it’s terrifying to learn that we thrive only within the thinnest of margins—only a half-degree room for error—this a revelation to me too: We strive to stay within these bounds. Despite being left too dry, in the wrong place for far too long, over-or under-handled, living things seek air pockets. Beings with a beating heart embody a drumming hum: we, we, we, it seems to say, try, try, try; and even though it often fails, it’s hopeful to me—(wetry, wetry, wetry)—this improbable beat that pushes and thrums, this beat I didn’t know we had until I saw it pulsing in a dark place, this beat that holds us fast on the wobbly orbit of a hurtling earth so we might come back around and back around, weary, seeking right.

Bowen is one of the writers included in the “5 over 50” feature by Poets & Writers magazine, which profiles authors whose debut work was published later in life. The Book of Kin is a reflection on decades of Bowen’s life and powerfully combines observations about generational trauma and the impact of incarceration with Bowen’s personal stories. The memoir is a testament to the power and persistence of love, reminding us that we can’t look to systems or institutions to save us, but rather to fostering connections with individuals.

The Book of Kin: On Absence, Love, and Being There by Jennifer Eli Brown

Milkweed Editions

October 21, 2025

9781571311672

Emily Webber is a reader of all the things, hiding out in South Florida with her husband and son. A writer of criticism, fiction, and nonfiction, her work has appeared in the Ploughshares Blog, The Writer, Five Points, The Rumpus, Necessary Fiction, and elsewhere. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated. Read more at emilyannwebber.com.