A Literary Reflection by Ellen Meeropol

A Literary Reflection by Ellen Meeropol

“I long for books about crazy people,” begins Lydia Kann’s luminous graphic novel, Germaine’s Daughter. “Maybe crazy people who have survived the Shoah – The War. There cannot be enough said about growing up with a crazy person who survived the Shoah” (1).

From the pogroms in Poland to the Resistance in France to a marginal existance back and forth between New York City and Los Angeles, this intensely personal story unspools against the enormity of international turmoil. We see a small-statured woman who survives war, raises her daughter as a single parent in refugee communities on both coasts, and teaches her girl to love both the city and the ocean.

When Germaine’s daughter is a child, the mother is fun. The daughter “likes having a goofy, cool mom. It feels warm and cozy and safe.” (42). But when she is fourteen, things change and the daughter takes over the third person narration. “The mother goes nuts. Nuts as in crazy, as in psychotic. The daughter doesn’t know the word for what’s happening, but she knows something big has changed” (53).

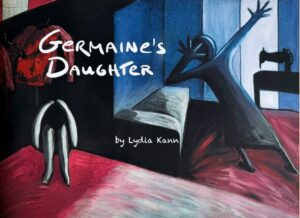

The text is both spare and emotionally-taut, benefitting from Kann’s skill as a therapist and her willingness to look deeply at her experience. It is paired with evocative paintings almost too large to be contained on the page. The images range from faceless figures in shades of gray to boldly colored scenes. What strikes me most about the art is the movement of the figures, especially the gesturing hands, beseeching the reader to enter this world and understand the daughter’s questions, her growing up, her choices.

This book is personal to me.

Like many Jewish grandchildren of refugees from Europe, I’ve read dozens—perhaps hundreds—of novels and memoirs and accounts of the pogroms and the Holocaust. Few carry the strong simplicity of Germaine’s Daughter, the sense of delving deep into the author’s pain, memories, and research while never letting go of the thread of how suffering can transform into hope and beauty.

I’ve known Lydia Kann for over fifty years. I’ve heard pieces of her past, both from our conversations and from her stories and essays. I’ve heard her describe her trips to France and Germany to find lost relatives. I’ve met some of them. I’ve read her short stories and novel manuscripts, attended her art shows, and have one of her paintings hanging in my bedroom. But none of that history prepared me for the muscle of her words and art together. For the power of the hybrid of writing and painting to illuminate the combination of trauma and love connected by simple threads from past to future.

In an almost magical fusion of a complicated inheritance, her insights as a therapist, and her talent as an artist and writer, Kann has created a visual story of trauma and illness, of claiming selfhood, and of sharing her strength and hope with her sons and her readers.

Germaine’s Daughter, a graphic novel by Lydia Kann

221 pages, paperback

978-1-948192-29-3

Ellen Meeropol Ellen Meeropol is the author of the novels Sometimes an Island (forthcoming in March 2026), The Lost Women of Azalea Court, Her Sister’s Tattoo, Kinship of Clover, On Hurricane Island, and House Arrest, and guest editor for the anthology Dreams for a Broken World. Her work, which often focuses on the lives of women on the fault lines between activism and family, has been a finalist for the Sarton Women’s Prize, longlisted for the Massachusetts Book Award, and selected by the Women’s National Book Association as a Great Group Reads.