Review by Sharon Tracey

Review by Sharon Tracey

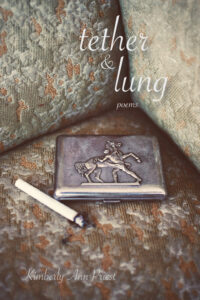

In tether & lung—Kimberly Ann Priest’s second full-length poetry collection—the poet threads finely wrought narrative poems borne of unrequited love and desire, grief and trauma, and the scent of shame never far off as “every animal has its own master.”(3) Divided into four parts (The Gelding, Her Hand, A Tether, Of Lungs), the sections also echo the four chambers of the heart and the lungs each partner tries to inflate, even as a marriage has lost its oxygen and died. There’s also generational history here, the recurring discomfort of bodies not feeling true.

Priest invites us inside her “house of lungs” as she absorbs the sensations of restriction, grief and loss and wrestles with what her world has become. Vulnerable and questioning, her poems are soft arrows for understanding the self and a closeted husband. The poet’s own children are subjects in a few poems, but are largely kept at the edges. And throughout the collection, one finds the solace of horses. The husband who kisses and loves them with tenderness, spills his secrets to them, but cannot do the same for his partner and children.

Early on we get “Film Noir [with Car and Cigarette]” (6), dark with moral ambiguity, reflection, regret, powerlessness. The poet writes:

Smoke in nostrils— language.

A gag of words that wick and saddle and chew,

the driver’s-side door creaking and plowed cornfields

rowing by.

My lungs seize up.

He tells me to roll down the window.

…

Frosty January cold fills my lungs.

—I worship inhalation

to make the silence natural.

Priest’s poems are masterful in their moodiness, evoking a winter’s silence between a couple over the years. Time hovers inside and over the poems as the poet yearns for what she cannot touch. Poems are pent up, filled with tension that simmers on the edge of explosion. A sideways glance that might be the eyes traveling across a page or the back of an open hand. There’s “another smoke” in the middle of the night, “His jawline always stiffened when he returned to kiss me” (11). In “The Good Wife” Priest admits, “I use gauze and tape to set the rib, / but feel it is not enough.” (14)

Rural hours fill with snow and cold, a heavy blanket of family and religious norms pressing down against exposing truths. Priest’s language is often visceral, replete with a vocabulary of foreboding and violence, words like: stamp, hanging, hook, knife; burning barn, bolted doors.

Poem titles reveal a narrative arc that charts the breakdown of a relationship forged by marriage but moribund from neglect: “My Husband Tells Me He is Gay,” “A Needle is Found Protruding from a Bone,” “The Dead,” “A Tattoo is Inked Over Our Scars,” “Divorce.” In the latter, the title reveals half the story, while the other half resides within the lines, as the poet declares the opposite: showing ways he was loved and could love, even if it was the care and feeding of horses, canning jam, or turning on a bathroom fan to lessen the steam. The poet recognizing small things to love, even in the harsh cut of two lives.

“His Fist” (39) brims with the innuendo of domestic violence: “curled like / an unbloomed crocus / around a tiny bee— / tiny hate— clinging to its center, / its wings / blaming God / for isolation—”. We see things in shadows, just outside the action. “The Scrape” provides a backstory, enough to orient and then raises hackles (43)

…the awful scream you tore through me

after dinner in the bedroom, the children’s ears barely

out of reach.

…

you’ve named me, again, the things you feel are you:

adulterer, liar, insane. You shift your weight…

Throughout, Priest paints vivid landscapes with words. Tight spirals of rolled hay (49) that “dot the landscape like butterscotch pinwheels / I trace on the window with my finger /before walking outside to ornament my eyes /with the picturesque view.” And “In the morning, when sunlight slices our bed / into single servings of cake—lines repeated / through the window shade—” (50).

There’s also a gauze that adheres to some poems: “a window / framing the benign wilderness of ghostly stars, frost, / and anorexic trees” (34) and a “Sunrise behind a curtain: thin fortress against / the over-bright dawn” (59).

In one of the penultimate poems, “Poem [with Garden & Ghost & Issa]” the poet writes: (66)

I am trying to repent—

of the subtle language of kisses,

how his lips parted only just

so, enough;

and honor the crossing of our bridges

with sackcloth and ashes.

…

until, says Issa, all our world [is] dew.

The world fleeting and changing forms—smoke, sweat, shadow. And in tether & lung, Priest deftly shows how setting down grief and trauma in words can free, can be an untethering.

tether & lung by Kimberly Ann Priest

Texas Review Press, 2025, $21.95 [paperback]

ISBN: 978-1-680-03406-6

Sharon Tracey is a poet and editor and the author of three books of poetry: Land Marks (Shanti Arts 2022), Chroma: Five Centuries of Women Artists (Shanti Arts 2020), and What I Remember Most is Everything (All Caps Publishing 2017). Her work has appeared in Radar Poetry, Terrain.org, Lily Poetry Review, The Ekphrastic Review, and elsewhere. She previously served as a director of research communications and environmental initiatives at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.