The most perilous part of girlhood is that it ends: on Melissa Fraterrigo’s The Perils of Girlhood

The most perilous part of girlhood is that it ends: on Melissa Fraterrigo’s The Perils of Girlhood

Review by Anna Rollins

Melissa Fraterrigo’s The Perils of Girlhood: A Memoir in Essays speaks of topics such as sexual violence, eating disorders, miscarriage, and medical motherhood. In Fraterrigo’s essays, adolescence is painted in golden strokes, sunny poolside summers and slam books at school. And while violence often awaits the narrator in these idyllic scenes, the true danger lies in the passing of time: when the pages of girlhood turn to womanhood. Fraterrigo’s memoir in essays explores how the inevitability of aging and death impacts one’s coming of age, work life, pregnancy, and parenting. For Fraterrigo, the most perilous part of girlhood is that it ends.

The scariest part of girlhood, Fraterrigo contends, is that it will turn into womanhood. And while youth is sunshine and softness, adulthood is dark and bulging. She writes of one adult woman: “We think Ms. Neely must be the ugliest woman alive. Once a nun, now she wears plain-colored polyester pants, her saddlebag hips coming and going, jelly skin and belly bulges. Black moles on her face sprout hair. We don’t say it aloud, but we fear growing up and growing out. We want to wear bikinis forever, toss our hair back and laugh at jokes, coat our lips with colored wands. We know how to be girls; we know what’s expected of us; we cannot respect the older women who forget their bodies and haunt our futures” (28).

In this portrait, Ms. Neely acts as specter, a gruesome reminder of a body that will slip and splay, decaying unto death. This adult woman acts as a harbinger. Hardly a role model, Ms. Neely serves as a warning of what awaits should a girl lose mastery over her body and her life.

This desire to retain girlhood fuels Fraterrigo’s adolescent eating disorder. Recounted in frenzied flights, Fraterrigo describes a time of her life marked by scissor-kicks and Tupperware containers filled with lettuce leaves. She’s hungry and diligent. She wants to win, and she wants to be wanted.

Eventually, she loses enough body fat to no longer have a period. Her mother takes her to a doctor, and there she is asked if she wants to have a baby someday. Her mom speaks on her behalf and says, “of course she does” (30).

Fraterrigo’s adolescent self stays silent on the page – but inwardly, she begs to differ. She does not envision motherhood as expansive, but as a state that turns a girl into a woman “weighted down by sticky hands clawing my knees” (30). She doesn’t want babies or adulthood: she doesn’t want to morph into Ms. Neely.

Instead, she asserts herself: “I will be the beautiful one. I will wear sequined ball gowns, step out of sleek limousines, my manicured hand on the lintless jacket of a handsome man. Everyone will look. They’ll eye the cut of my hair, the lean fit of my dress. They will be amazed at how tall I stand, how perfectly ordered. I have plans too” (30).

As Fraterrigo grows up, some of her plans will lead her to the profession of teaching. In one of her first jobs out of school, she teaches writing. In one writing class, a male student challenges her authority and writes sexually explicit material about women. During office hours, he threatens her and undercuts her position by calling out her youth: “You don’t look old enough to teach this class,” he argues. (71).

In this scene, Fraterrigo is targeted due to her age. One might wonder if Ms. Neely would receive such harassment. Fraterrigo recites her qualifications to herself – her extensive publications and education – as if she needs to be reminded. As if she hadn’t lived every single one of her own experiences. Still, she is an adult who looks like a girl – and this discrepancy is what places her in danger. In this experience, she sees how sometimes the very thing that gives you power is also the thing that can place you in peril.

Like any girl lucky enough to continue on, Fraterrigo does age into womanhood. She eventually warms to motherhood, too. This experience, as she anticipated earlier in the book, does change her, though not because sticky hands are weighing her down. She changes from the inside: “A woman’s brain actually changes with motherhood. In the maternal brain, the amygdala, which manages memories and fear reactions, is strengthened in the weeks and months after childbirth. Coupled with hormones, some of the new neural pathways that develop are dedicated to vigilance and survival.” (135).

And Fraterrigo’s vigilance will be critical for her child’s ability to survive her own girlhood. Her toddler daughter, Eva, begins having seizures. If she keeps having seizures, she may never be able to drive or play sports. Her ability to grow up will be stunted. Or, of course, she may never be able to grow up at all. (109).

In one harrowing scene, Fraterrigo recounts the time that their family almost lost Eva completely. It is at this moment that the memoir makes its turn. The narrator, now a woman, fights for her own daughter. In this becoming, Fraterrigo grows, not into the older woman who haunted her, but into someone more expansive, someone living for more than just beauty and order and acclaim, but for the life of another.

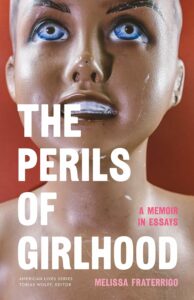

The Perils of Girlhood: A Memoir in Essays by Melissa Fraterrigo

University of Nebraska Press, September 1, 2025, $21.95

ISBN: 9781496242204

Anna Rollins’ memoir, Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up as a Good Girl, examines the rhyming scripts of purity culture and diet culture. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Slate, Salon, Electric Literature, and other outlets. She runs a free monthly series on Substack called “Path to Publication” where she shares pitches for work she has placed in popular outlets. Follow her on Substack and Instagram.