Review by Emily Hall

Review by Emily Hall

Miranda Schmidt’s debut novel Leafskin is slippery. Part prose, part poetry, the novel begins as a realistic portrayal of a woman struggling to conceive. The protagonist, Jo, is undergoing IVF treatments with Liam, her husband, while they simultaneously navigate deadly wildfires. As the novel progresses, however, the realism gives way to folklore. Jo reunites with her former lover, Ness, a rebellious artist who insists that she is a selkie, a shapeshifting creature that is part-human, part-seal. Eventually, when Jo conceives a child, she suspects that it, like Ness, will be a shapeshifter.

Leafskin is an ambitious work of queer ecofeminism. Over the course of the novel, Schmidt (who uses they/she pronouns) raises important ethical concerns about choosing to have children knowing they will suffer the effects of climate change. As Jo begins her fertility injections, she builds a “‘Wall of Destruction,’” or “clippings […of] articles about dying habitats, maps of flooded coastlines” (23). While Liam tries to talk her out of its construction, Jo wants to acknowledge that her child will inherit a world on fire. Amidst these fears, Jo often looks to trees, particularly sequoias, as guidance, acknowledging that “their seeds grew in ash,” an adaptation that allows future generations to survive (29).

Schmidt’s novel is the most compelling when it explores the relationship between survival and shapeshifting. A poet, Jo finds inspiration for her work in the myth of Daphne, “a nymph running from Apollo, turned to a tree by a river god to make an escape” (49). After a period of writer’s block, Jo experiences creative renewal when she and Ness craft hybrid works that blend art with writing. Jo refers to these collages as “paintpoem[s],” creating a compound word to describe their collaboration (82). This whimsical, linguistic playfulness is scattered throughout the novel, as Schmidt forges new words to better capture nuance.

Jo’s desire to write poetry, even as she is surrounded by ecological destruction, calls into question the function of literature in chaotic times. Just like bringing a child into a burning world is an act of optimistic defiance, so too is writing literature rebellious. When Liam accuses her of not doing enough to mitigate climate change, Jo rebukes him, insisting, “‘[p]oetry isn’t nothing’” (173). Eventually, she reasons that her poems allow her to write “toward something” (181). Her belief that poems can alter and improve the world echoes the novel’s many images of seeds, which are dispersed in the hopes that they will find a future.

The ability to adapt in uncertain times shapes Leafskin’s depiction of families, bodies, and gender in ways that are both interesting and perplexing. When Jo finally has her baby, she refuses to reveal its gender, even to readers. Referred to only as “River,” or the nonbinary “they,” Jo’s child is drawn to nature even as a baby. Their desire to converge with nature dovetails Jo’s fervent belief that infants are not humans, but plant bulbs full of potential (31). Readers understand that River will be more adaptable to climate crises than other people, and part of this stems from how they are conceived. That said, while River’s parentage is a fascinating approach to what it means for a queer couple to “have” a child, this plot point is somewhat disjointed, especially as it leaps between reality and folklore with little reflection from Jo.

While Leafskin raises many contemporary, urgent issues, it tries to cover too many at once. As a result, the novel’s pacing suffers. Some readers may find the brief chapters choppy, while others may have to read well into the novel to discover the threads that bind the story together. However, Leafskin is still a moving, elegiac testament to how mothers worry about the world their children will inherit.

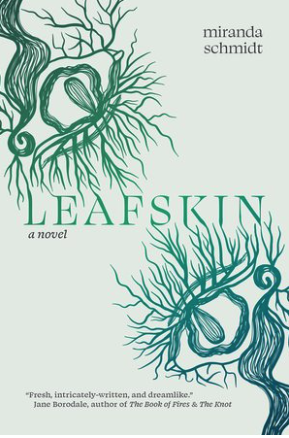

Leafskin by Miranda Schmidt

Stillhouse Press, 2025. 309 pages. $18.00.

ISBN 9781945233289

Emily Hall (she/her) has a PhD in contemporary Anglophone fiction from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her creative prose and book reviews have appeared, or are forthcoming, in places such as The Portland Review, Necessary Fiction, 100 Word Story, and Cherry Tree. Her academic scholarship explores queerness, disability, and belonging and has appeared in places such as South Atlantic Review, Reception, and The Journal of Medical Humanities.