Review by Constance Clark

Review by Constance Clark

To evoke mother in our thoughts and emotions, rarely do we think of fluidity. More often, stops and starts, bumps in the road, outright rage. I suppose, continuous flow of love could be the anomaly in some mother-daughter relationships. But not mine, nor Nancy Gerber’s deeply honest glimpses into her mother bond in her poetry chapbook Language Like Water. Her retrospective poems drip words of mother-daughter complexity in short quiet poems that taunt a range of emotions, and speak to her success as a poet, a finalist for the Gradiva Award in 2014 with her book of poems Fire and Ice: Poetry and Prose and author of other published chapbooks.

Her title poem, “Language Like Water” and the opening poem in the chapbook, is almost a non-sequitur – the only poem that speaks to hand-holding and open love:

a fluid holding of all things—

dreams, hopes, secrets.

Fused,

floating

oceanic embrace (1)

I was taken with this alliance, felt the fluidity of what would be gorgeous conversations, understood nuances between a daughter and her mom as they moved from girl-mother to friends. But the language of the poems ran elsewhere. And logically then, the collected poems provided an arrival to the first poem – as Christine Redman-Waldeyer, editor of Adanna Literary Journal noted, Gerber resurrects “the sanctity of truth” that we come to know via frustration, guilt, loss, and grief.

As we slip around time from childhood to her mother’s death and beyond, powerful imagery scaffolds these truths. In “Portrait of Mother and Daughter” we feel the pain within the relationship in the lines: “The color of women, / bruised and bleeding.” (3) In “The Night I Tripped, Age Three,” a mother “weeping at the / foot of the table” (4) and in “Ballet Class,” (6) a mother who locks herself in a bathroom, sobs, and later defends her four-year-old’s actions. This mother was troubled but trying. In the poem “My Mother’s Kugel” that attempt comes through again, despite the sense of loneliness, the two-sided truth:

We shared it

Sunday mornings

just the two of us

luscious layers

bridging the distance,

fault lines dividing us,

a slice of peace. (18)

In “Queen of Bakeries,” we experience a stream of emotions the daughter feels. In the poem, the mother, now eighty, wanted to bring three favorite cakes – no doubt for a slice of each – to celebrate at a restaurant. The daughter refused her, but the movement from amusement to guilt runs throughout the backstory and ends in regret:

I’m bringing all three.

You can’t, I say.

Too many.

One cake, that’s all.

Her eyes filled with tears.

I was cruel to make her choose. (13)

Daughter-mother guilt is a direct hit in “A Good Daughter” for the speaker and surely for our own souls. We can’t help but cringe when Gerber admits that if she “were good” she would not have placed her mom in a nursing home.

A good daughter

doesn’t put her mother

in a place like this. (14)

I’m not sure if it was the poem “My Mother’s Wisdom” or “Vintage” that anchors the pivot from frustration to loss in this chapbook. The first, a golden moment and an image at the start like no other in the speaker’s words or experience except once more at the end of the poem:

In the armchair framed

by sunlight, she told me

“Letting go

is the hardest part.”

Those words—

the hard shell of us

finally

cracked open. (12)

The second, “Vintage,” the softening of fraught memories into forgiveness. “You’ll see, he said / when she passed.” Presumably, the words of a friend or husband. “Fond recollections / will flood back.”

What follows in the poem is just that – a surge of memories about rings her mother offered to her over the years in Gerber’s tight, sparse flow of words both gorgeous and fond:

So many choices—

opal, ruby, pearl.

Their gold bands

enchanting,

circlets of truth—

my choice,

her love. (20)

My favorite poem in the chapbook is “Curvature” because it pulls us into the unavoidable experience of the advent of the death of a parent with the exceptional and unique images of a seahorse, a jellyfish, and a shell. To me, a transformation of ugly decrepitude into a remarkably unsentimental vision of a mother’s deflation illogically into ocean waters:

My mother lies curved

like a seahorse

Bones poking through

bruised

jellyfish skin

Coiled in her shell,

mind out of reach. (15)

At the end of this poem, the daughter reaches out to touch her living mom for the last time: “I place my finger / on her thin / blanched wrist.” (15)

And these words carry us back into the emotional landscape of “Language Like Water,”—

Fused,

floating

oceanic embrace (1)

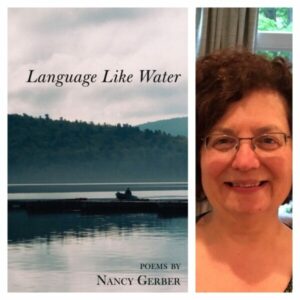

Language Like Water by Nancy Gerber

Finishing Line Press, 2024, $17.99

ISBN 979 8 88838 799

Constance Clark is a writer and retired teacher from central NJ. Her poems have appeared in Litbreak Magazine, Heavy Feather Review, and Moonstone anthologies. Others are pending. She is currently working on a collection of micro-nature poems with the inclusion of a long poem related to the 72 Japanese microseasons.