Review by Joellen Craft

Review by Joellen Craft

Too Much to Ask: Bridget Bell and the Toxic Positivity of American Motherhood

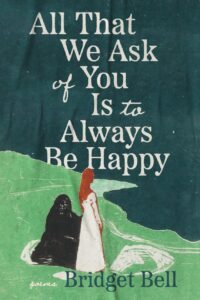

In the midst of a great era for “mommy poetry,” Bell’s debut, All That We Ask of You Is to Always Be Happy (CavanKerry Press, 2025), offers something new: a medically accurate and well-researched portrait of postpartum and perinatal mood disorders. Bell’s book lets us into the brain of a mother on the edge, a mother in need of help; and through her use of research and wrenching, to-the-point lyric, she reminds readers that more mothers than we’d like to acknowledge are on this edge. Even more important, Bell gives those mothers what they need: an ally.

The book centers loss familiar to all caretakers: loss of self, loss of sanity. The first poem is written to an expectant mother, urging her to

listen to the zip of white leather

boots, flaunt them with a storm-stomp

like lightning

and to “cherish the body of the woman / you will never be again” (“Directive for Women Who Are Not Yet Mothers but Will Become Mothers”). Along with this loss of body comes other losses, like loss of time: “Each stagnant week and its million days” is listed as a cause of perinatal mood disorders, in a poem dedicated to “the mother whose body is jerked / by babies that tug like puppeteers” (“This is for the mother (Perinatal Mood Disorders Inpatient Unit)”).

This loss and transformation are often heartbreaking, as in “This Is for the Mother (Intrusive Thoughts)” written “For the mother who washes the knives quickly to get them out of her hands” but also often humorous, as in “Portraits of Postpartum Anxiety,” where the speaker says,

my friend’s finger is tapping

on my bedroom window

and I’m pretending to be asleep

because how fucking urgent can it be

that he gets back his Pyrex, his serving spoon

from the kale salad and the broccoli fritters?

Bell also channels Sharon Olds with blunt sentiments made beautiful, as when she describes

the fetus

that entrenches itself in the space

made for your organs as it claims your body

from the inside. (“This Is How You Lose Your Body”)

The tension between grace and muscularity in these lines reveals how deeply the ligaments of depression, and the feeling that such feelings are wrong, are interwoven with the experience of motherhood.

Take “Pressure,” a poem whose opening lines state:

We cry over spilled milk

yell shit at the elbow

bump that puddles the pumped

sweet gold onto the kitchen

counter.

The lullaby-esque internal rhyme and rhythm pulse beneath the speaker’s frank description of the heartbreak many new parents experience: literally weeping for spilled pumped breastmilk. In Bell’s hands, motherhood and postpartum depression can be neither only brutal or only beautiful, as at the end of “Plea,” when the speaker asks her partner: “Swear on your life. / Later, you can waver, / but promise me now that I am still your wife.” That poem’s song-like music ends on stark imagery:

I am a translucent shell,

my shed exoskeleton clinging

to the slope

of a tree trunk,

abandoned where my body crawled

through its own skin. (“Plea”)

The poem’s longest sequence, “Co-Opting Anne Carson’s ‘The Glass Essay’ to Process My Miscarriage” has similarly stunning tonal shifts. The poem opens,

The baby’s shape is a sea monkey, a pink shrimp. It smiles and waves little hands at me. I wake up, remembering

I miscarried yesterday. I am freshly un-pregnant.

As the speaker waits first at the ER, then her OB’s office, she documents the language that demeans, erases, and ignores her loss, as well as her acceptance of her own cognitive dissonance, from the phlebotomist’s chatter to the pamphlets titled, “Nap? Snap!” In this poem and others, Bell’s speaker clocks a general indifference from providers: one doctor recounts a story of “a lovely woman” whose “vagina…exploded, how [they]mended her erupted flesh…like … patching a hole in jeans,” all while “his face is framed by my open legs. Her husband should send me flowers, he says as he pushes through me with a needle and thread” (“My doctor recounts to me an anecdote”). Within the collection, too, are doctors who take the time to listen, notably Dr. Riah Patterson, who wrote the medical introduction, and the provider in “Dangerous for Mothers” who asks, “And how’s mom doing?” before “squeezing / my other hand, admitting she didn’t love her son, really love her son, / until he was four months old.” Gaining entry into this space, where admitting she was not okay was okay, is a major turn in this book. In that same poem, the speaker finally understands

I was not alone that summer—

everywhere are always women who stare down at their babies

and wish them away, begging to wake up years earlier

lonely and free.

The phrase, “everywhere are always,” awkward and full of vacant, echoey vowels, points to the stuttering mind and logic of a woman who has been gaslit, who

watched greeting cards pile up,

pale pink and sparkly: blessing, little angel, princess, precious.

And then the crumbling would appear again, like a mudslide

caving in a village. (“Dangerous for Mothers”)

Bell’s speaker eventually gains confidence in realizing

you are plentiful,

One of countless women who winces at rolled-back eyes,

white slits under thin, flicking lids. …

you are not alone. (“Collective”)

Such moments of strength in community, and in family, dip in and out of the speaker’s awareness, in service of the speaker’s journey through the lowest levels of her personal hell. What saves her, however, is her own sadness. While the book has, up to this point, been threaded through with the italicized voices of friends, doctors (peering between the speaker’s legs), and family, the final poems use italics to signal the speaker’s own incisive thoughts, and are especially expansive, exploring the roots of her sadness much like a researcher digging for clues:

for while con is with as in with love, with joy,

con is also with child, as in the child

What struggling mothers groping their way through postpartum or perinatal mood disorders need isn’t more cards, more Chinese takeout, or more naps. They need attention and treatment to gain agency over their fear, like Bell’s speaker encountering a black widow spider in “On Not Waiting It Out to See If I Feel Better”:

to leave it alone

is the most ruinous choice

I could make

so instead I heed the signal

of danger marked on her glossy body

that hangs

upside down smash open

the red hourglass turn her poison

into rubies and fill my hands.

Bridget Bell is a poet, educator, proofreader, and bartender. She teaches composition and literature at Durham Technical Community College, proofreads manuscripts for Four Way Books, and pours pints at Ponysaurus Brewery. Raised in the suburbs of Toledo, Ohio, she earned her MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and currently resides in Durham, NC. All That We Ask of You Is to Always Be Happy is her debut collection. Find her www.bridgetbellpoetry.com.

All That We Ask of You Is to Always Be Happy by Bridget Bell

CavanKerry Press, Feb. 4, 2025. 88 pages; paper.

ISBN: 1960327089

Joellen Craft is a Pushcart Prize nominee who lives with her family in Baltimore, Maryland, where she writes and teaches. Her poems and reviews have appeared in Lines + Stars, Adroit, The Laurel Review, The Fourth River, Radar Poetry, Hunger Mountain, Grist, The Nashville Review, and others. Her chapbook, The Quarry, won L+S Press’s 2020 Mid-Atlantic Chapbook Prize. Find her at www.joellencraft.com.