Review by Katie Kalisz

Review by Katie Kalisz

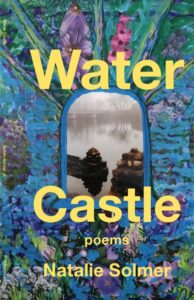

Natalie Solmer’s debut collection Water Castle takes as its muses water, grandmothers, and ancestry. It has three sections, “Snowbelt Wind”, “Motherland”, and “Map in My Palm”, 38 poems in total.

Each section begins with a water castle poem. In the first, the speaker invites us to “consider, with [her], [her]moats” (15). That poem proceeds to act as a kind of map of the speaker’s whereabouts and dreams she’s let go, places she’s moved to, tended, rented. “Water Castle No. 2” starts with the Gustav Klimt painting “Water Castle”, but then spirals outward with lines about origin from Nancy Chen Long, before returning to Klimt’s Vienna, the speaker traveling with her sister. She mounts a series of questions about her family who immigrated, things that she was “not allowed to ask”, and confesses to “want[ing]nothing of [her]bare root” (46). In the final water castle poem, the speaker recounts how she sees herself (and her ancestors) more generously through her relationship with her lover and her children. In “Water Castle No. 3”, images of water return but they take different forms: “melted snow” (71) and “wet seasons” (72). The family and love “emerged out of a lake” (72). This last section brings the past and present and future together, with poems about a lover, his Caribbean family, and the children that come.

Water is studied and worshipped in this collection. The speaker refers to herself as a fountain, a great lake, a deluge, a river. Water is changeable, it expands and contracts, like the speaker leaving and returning, searching for a homeland and then pushing it away, seeking solace and disappearance and belonging in her lover’s culture. For this speaker, “everything is separated / by water: / our homelands and our expectations / of love” (85).

“A City on The Edge of Your Border” claims “this river is my ancestor, / artery, the genetic code” (30). The speaker is told she has a “lake face” (16), and admits she has “always the shadow of water / a lake howling in [her]hair” (50). This notion is repeated in other titles in the collection: “Girls of Lake”, “I Am a Great Lake”, and “Girl of Water, I Could Swallow A Garden”. Later, women and nature are equated: “A society treats nature / the way it treats its women” (32). We can’t help but to recall this line with every mention of nature (and women) that follows.

But the speaker also identifies as a moat, a border, a shovel, a trellis. These identifiers fit with the mix of rust belt Midwestern and nature images. Lines like

I am old as the bats

that swarmed the summer evenings

around the baseball stadium lights, the empty

factory’s brick façade behind them (47),

show how the speaker claims the places she inhabits, becomes them under their influence.

These poems connect generations and interrogate the choices that have been made. The speaker is visited by her ancestors, her grandmothers, seeks to know why they came here, charts the distances between points on a map, where parents met, where she was when someone lived there; some poems triangulate and revisit places and people across space and time.

There is a dance between seeking ancestry and running from it. “A City on the Edge of Your Border” begins with the line “I wanted to be a cloud and forget my people” (26). In the poem just before it, the speaker says “My face is a border / made up of people born elsewhere” (24). In “Quiz: Find Your Face Shape, she continues, “my face is as wide as the shovel / of my ancestors who sold vegetables & / soldiered in the wars of the empires” (41). The quiz ends with this question: “how much / can we dent / the shape of our fate?” (42). We see the speaker grapple with what is inherited, “Whose lips? Whose nose? Whose poverty and sadness / in the gene?” (61), and also entertain chance: “By some miracle, some linked mitochondria, some ocean steamer, / I have been spit out here” (49).

In a similar way, several poems fight against erasure, especially the erasure of women and mothers, who are “easily…erased” (49). And yet, the speaker admits she is complicit in the erasure: “confused by what’s been erased, I erase more” (71). It is this honesty that forms the heart of the collection, and that draws readers into their own questions of self-origin and self-acceptance.

Water Castle by Natalie Solmer

Kelsay Books, 2024, 100 pages, $23, paper

9781639806454

Katie Kalisz is a Professor in the English Department at Grand Rapids Community College. Quiet Woman, her first book, was a finalist for the 2018 Main Street Rag Poetry Book Award. She is the recipient of a 2023 Elizabeth George Foundation Grant, and her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Her second book, Flu Season, is forthcoming from Cornerstone Press. She lives in Michigan with her husband and their three children.