Review by Jill Koren

Review by Jill Koren

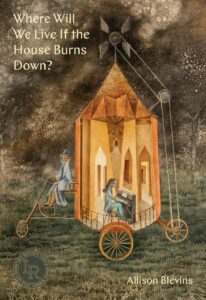

Winner of the 2023 Lexi Rudnitsky Editor’s Choice Award, Allison Blevins’s fifth full-length book, Where Will We Live if The House Burns Down? (Persea Books, 2024) certainly does its work in honoring the “playful love of language” and “fierce conscience” Rudnitsky’s own poems exhibit. Blevins, also the author of five chapbooks, extends her canon of works examining the inexpressible experience of living in a body in pain, a house on fire, among other bodies who burn and circle: “because there are the children. Always the children” (3).

While motherhood is certainly a recurring theme in this collection, it is not the core of these genre-bending vignettes. In fact, the search for a core may be the essence of this book, as Blevins hints in the first of two epigraphs: “Under this mask, another mask. / I will never finish removing all these faces” (Cahun). Yet Blevins begins the narrative by adopting a mask, and the reader meets Grim, the main character of this story-in-pieces, in the very first word of the first poem, in which Grim “finds herself lost” (3).

What follows is a series of losses and retrievals. The vehicle is the body, as it can only ever be, and Grim’s body is the locus of suffering. The body is the source of the pain, but also the poetry. Even when Grim herself is lost, “Her body remains” (3). It is this anchoring effect of the body and its needs that tethers us, reader and poet, Grim and Sergeant, mother and child, lover and beloved, spirit and flesh.

The search continues throughout the book, and while heavy at times, there are hopeful, even playful moments: “I’m worried that Grim is becoming the central figure of this story. I didn’t plan it. But here we are anyway” (10). The journey to understanding always leads back to the self, even by another name. The narrator’s wry acceptance of this uncomfortable truth allows the reader to settle into the warps and wrinkles of identity that Blevins pulls taut for us to see.

When Grim’s pain doctor asks about her goals, she resists: “I want to tell him the chronically ill don’t have goals” (18). The resistance yields an admission: “Grim wants her old body back” (18). Yet goals emerge anyway: to stand in the kitchen, to check on the children. The mundane becomes heroic, goal-worthy. Anyone who has struggled with recurring pain or fatigue can take comfort in this. To live is to experience recurring pain.

Though getting her old body back is not in the stars for Grim, she wrestles with her current one: “Grim has internalized hatred of the aging body” (57). Yet this ingested loathing is balanced by a muted love in the fear of further loss: “Where will we live if the house burns down?” Despite their flaws, Blevins reminds us–our bodies are our only homes here on Earth, and we must tend them, even as they fall down around us.

In this tending, Blevins recognizes we must bind others to us, as the living must. Often this is a burden. In the middle of a recurring argument Grim asks the Sergeant what he needs. He replies, “I need you to need less from me” (41). The ache of this admission echoes throughout the book. Yet the Sergeant stays. And Grim regards him, with a range of emotions that allow him space to be.

Other characters round out the view: Grim’s mother, whose repeated stories question the veracity of any story while also reiterating the necessity of them, of the repetition. Similarly, Grim folds things to fit her needs: the Sergeant, her own body around her child. In these folds, these repetitions, joy is found. A writer friend appears to affirm this unlikely joy, which spreads like pain, familiar, through Grim’s body.

In this book, Blevins attempts to witness a woman’s life–her own–through a fragmented narrative of linked lyric-essay-like prose poems. The genre bends as truth does, as perception, as “code” for what we take as truth, or what we know to be truth but cannot say directly. In this encoding, Blevins has provided a gripping picture of a woman moving through a fog of pain and joy, gaining control of the uncontrollable by setting it down in fragments, feeling it all. The pain becomes like the weather, ever-present, yet the pen allows the author to decide when it will rain. Grab an umbrella if you must.

Where Will We Live if The House Burns Down? by Allison Blevins

Persea Books, 2024, $17

9780892555955

Jill Kelly Koren is the author of three collections of poetry, Though the Word is a Lie and The Work of the Body, (Dos Madres Press), and a chapbook, While the Water Rises Around Us, (Finishing Line Press). Her work has appeared in journals such as Literary Mama, The Louisville Review, and Redheaded Stepchild. Koren teaches creative writing and literature at Ivy Tech Community College in Madison, Indiana, where she lives with her family.