Review by Jiwon Choi

Review by Jiwon Choi

Jen Karetnick’s new poetry collection offers up layers of understanding and wisdom on how to live in our wild and crazy times. The poems that make up Inheritance with a High Error Rate operate in a backdrop of solemn joy that manages to be both profound and delightful. Case in point, meet the octopus who finds a coconut shell in “Play, with Foreign Object” (23):

And then

it rolled and bounced, propelled by

the predictable tide. And the whole sea

shuddered with this shred of saturated joy.

Karetnick, author of eleven poetry books including The Burning Where Breath Used to Be and co-founder and managing editor of SWWIM Every Day, is a poet who understands that we are not the only creatures seeking to engage the universe with all the verve and velocity we can muster. Here is a poet who brings to light the conundrum of being alive during our epoch of breathtaking beauty and overwhelming cruelty; alive in an era where seeking enlightenment and clarity does not absolve us from not doing enough for each other, for the planet, for our non-human creatures, for the generations to come.

I hear in these poems the question: How will we resolve this dissonance of morality without succumbing to our basest instincts, without turning away from our better angels? Well, there are no guarantees. But take heart, all is not lost, as the poems do offer algorithms and trails of crumbs that lead to some clues on how to make sense of the useless noise threatening to engulf us.

Provided you pay attention.

At first glance, we might consider abundance as a counterbalance to the pain of losing loved ones, aging, estrangement, political rancor, species extinction (the list goes on). And in the love language of mangoes, abundance represents resilience:

thrusting up seedlings when no one is looking, that might

or might not bear if allowed to grow, but will be

considered new varieties if you do, those genes

throwbacks to every Asian, Latin and Caribbean

tree that contributed to your lineages.

(from “Mango: An Inheritance with a High Error Rate” 22)

But then again, the speaker has grown weary from loving these “fragrant wild grenades” for so long, as they end up in “dishes to spoil in the back of the refrigerator,” and food pantries will not take them “fresh, and unprocessed” as they are because America doesn’t “embrace anything: in [their]colorful, foreign-born skins” (22).

Or perhaps it is the “independent bison” in “Promise City by the Numbers” (66-68) who will lead the way:

through 9 months of cemented snow

with the determined shovels

of their hooves to find ox-eye,

goat’s rue, and rattlesnake master,

who lead themselves to water

at deceptive local ponds

that don’t freeze all the way down

to their muddy seats

but then again, they end up on platters for “meat tasting”.

But really it is getting a handle on the significance of the inheritance in question that will help clear our heads and hearts. For we have been trailing its heady perfume and “molten juice” throughout the book, and though we do not encounter it in all the poems, we feel its presence. The mango as inheritance is not the sweet bounty we first thought it to be.

Almost four decades earlier, when Mary Oliver wrote “The Mango,” conjuring visions of “jungles, and death,” ships loaded with mangoes leaving harbors (making me think of the other ships), “children, brushing the flies away from their hot faces,” as they toiled in the fields, at gunpoint, she did not hide her own complicity:

Things wound themselves together as they always do––

health, art, profit. Where to travel

for the best weather. Where to buy

the cheapest, the best and sweetest of anything.

I admire Karetnick for working to reconcile the truth for us and for herself in this age of war, mammon, meanness, and hyper-robotic drive, but now would be a good time to remember that truth doesn’t always feel good; oftentimes we don’t know what to do with how bad it makes us feel.

We have known for a long time that avocados from Mexico are a “conflict crop” meaning cartels wreak violence in order to gain control over its production and distribution. Not to mention the rapid razing of forestland to make room for more farms.

So how can we keep demanding and consuming in spite of these high human costs and collateral damage?There is no magic answer that will make us feel better, but Karetnick offers this reminder, and it is quite prescient:

What we think we own

will no longer be ours to claim

but the leaves of every book

we ever read, libraries

of poems lingering in the water

like sonar, will green

and green and green and green

(from “In the Photic Zone” p. 14)

Amen.

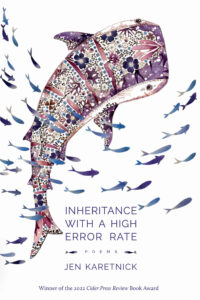

Inheritance With a High Error Rate by Jen Karetnick

Cider Press Review, January 2024

Winner of the 2022 Cider Press Review Book Award

9781930781641

Jiwon Choi is a poet, preschool teacher, and urban gardener. She is the author of One Daughter is Worth Ten Sons and I Used To Be Korean both published by Hanging Loose Press, as well as Choi’s third book of poems, A Temporary Dwelling, published by Spuyten Duyvil in 2024. She started her community garden’s first poetry reading series, Poets Read in the Garden, to support local writers. You can find out more about her at iusedtobekorean.com.