Review by Emily Webber

Review by Emily Webber

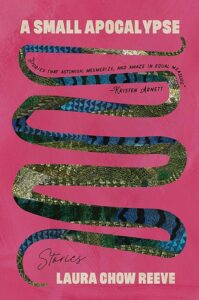

Laura Chow Reeve’s debut story collection, A Small Apocalypse, takes place in the wildness of Florida, following a group of queer friends in mostly interlinked stories as they form bonds with each other, defy expectations, and seek to learn more about themselves. Some stories are outside the bounds of our world and others entirely realist—one story is a packing list for the apocalypse, in one a woman is transforming into a reptile, in another a normal trip to Disney World turns tragic and bizarre. There’s also government-controlled dating, and impending hurricane, pickled memories in jars, and a flamingo stoned to death.

What runs through these stories, quietly but always present, is the racism and toxic actions by white people towards marginalized people. Characters are harassed for being mixed-race or told they are prettier because they are part white, another girl is asked jokingly (or possibly not) if she’s a native while she’s vacationing at the Polynesian Disney World Resort. But for all the negative outside forces pushing on these characters, they are looking inward, leaving homes and families behind for something new, leaning into their true identities, and creating their own communities.

“Suwannee” and “Migratory Patterns” both present the same group of queer friends first coming together to celebrate a birthday and then to send off a friend who is moving away. Seeing Reeve’s characters share space, even though the world surrounding them is flawed and their relationships with their own bodies and each other are messy sparks joy. From this group of friends, Reeve pulls individual characters to form most of the other stories in this collection.

“Rebecca,” a queer retelling of Daphne Du Maurier’s novel of the same name, introduces Rebecca, a core member of the friend group early in the collection. The story is told from the point of view of Grace, who travels from California to Florida to see in-person a man, Max, she met online. But Max quickly fades to the background, while Rebecca is ever-present even though she’s dead. The story moves into the more speculative at the end as Rebecca transforms into something more than a memory and ghost-like presence.

Rebecca’s memory haunts a few of the stories throughout the collection—”Suwannee” the one time where the reader meets her alive and other stories where she is remembered by others. In “Beloved Flamingo Stoned to Death,” Lou rescues the body of the dead flamingo from the zoo they work at so the flamingo can have a proper burial. This causes memories of how Lou felt at Rebecca’s funeral: “When it was all said and done, their friends had spilled out of the church tear stained. And Lou remembered feeling a sense of relief at the impossibility of ever feeling as useless as they did in that moment again” (126).

Other stories in “A Small Apocalypse” lean more toward the speculative. The first story in the collection, “Milked Snakes”, a woman is slowly transforming into a reptile causing her to question what she desires and her relationships with others. A grandmother teaches her granddaughter how to pickle bad memories in a jar so they can be forgotten until it later becomes clear to the girl that in doing so, she is losing what it means to be herself as she is already living in between two worlds as mixed-race person. In “Real Bodies,” queer relationships are forbidden and the government watches everything. State controlled dating matches people with approved mates, only allowing heterosexual relationships and either white people together or a white person and a person of color. The most startling thing about “Real Bodies” is how insidious the control becomes so it is hard for these characters to even remember the time of relative freedom from before, almost being tricked into thinking this is how it always was for them. The narrator longs for an intimate relationship with her friend Carol, but even close friendships between women are discouraged and monitored: “There are hotlines that your neighbors can call if they notice a friend is over too late.” She wants to touch Carol as she watches her getting ready for her government chosen date: “You tell her she looks beautiful. You are close enough to feel the heat coming off her body, close enough that you feel everything that makes up you and her. You think that you could live off this feeling forever. Even if you could never touch her, you could stand close enough to feel these vibrations, and it would be enough” (50). Then in some stories nothing out of this world happens, yet the weirdness always lurks beneath, and characters are haunted by ordinary life—of deaths, and breakups, and dead-end jobs—and so the different styles of stories work well together.

Every Florida collection should have a hurricane story where the impending storm is barreling down causing the character to reflect on their life choices. Reeve delivers with the title story “A Small Apocalypse” where Melissa is manning the town’s movie theater as its owners have fled out of the storm’s path. As the storm enters ashore and the theater begins to flood and fall apart, the ghosts come to haunt Melissa and once they burrow in, it’s clear they won’t be leaving.

Florida is more than just a setting in this collection, it is where these characters call home even though it is not perfect. And Reeve acknowledges the less than appealing parts of Florida. She shows flashes of the people who cling to the confederate flag, those who yell out slurs, and those unwilling to accept sexuality and identity can be fluid. But what Reeve always gives actual space to in “A Small Apocalypse” is characters who thrive despite this and find their own community and strength and truth within themselves.

A Small Apocalypse by Laura Chow Reeve

Northwestern University Press: TriQuarterly Imprint

March 2024, Paperback, 9780810146945

Emily Webber has published fiction, essays, and reviews in the Ploughshares Blog, The Writer magazine, Five Points, Split Lip Magazine, Hippocampus, and elsewhere. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated, from Paper Nautilus Press. You can read more at www.emilyannwebber.com and @emilyannwebber