Review by Katie Kalisz

Review by Katie Kalisz

Ellen Kombiyil’s second full-length collection, Love as Invasive Species, is dedicated at the beginning of Side A “for daughters” – as though daughters have it hardest, growing up through the inherited invasive love, deciding what to shed, what to keep, how to remember.

The collection is a double book, with poems that “mirror and respond to each other.” There are two ways to read this book. When I first sat down with it, I read it “straight” through, beginning with Side A, getting to the end of that, which is the mid-point of the book, and then flipping the book over and going to the beginning of Side B, the back cover which was the “end” of how I started. When I finished my reading this way, I wound up again at the mid-point of the book, arriving there from the opposite side.

After that reading, I started over, again beginning with Side A, but reading one poem from each section, so that I could hear them in conversation with each other. I was constantly turning the book over and flipping to find the companion poem from the other side.

Reading this book is a physical experience, and that fits the subject matter well. Readers are encouraged to get inside the book, almost taking it over – the way memories that are passed down and called love take us over, invading the present, interpreting how we see the present. Each side has twenty poems.

The speaker calls out to daughter, great-gramma, gramma, and ma, asking, teaching, remembering, retelling. In “Prayer”, the poem begins with “Daughter, if I forget to teach you / to hunger” (1B) and later, in “Ode with Aquatic Fauna” the speaker asks “am I a woman who, looking at her daughter, feels the current / of herself run through her” (10). Many of the poems hover over what is kept, what is remembered, what is sacrificed and what is desired.

There are arresting images of connection and rebirth. In “Birthday”, a “buried cat / sprout[s]a raspberry / bush” (2). In “Love Song with Contradictions” great gramma’s braids are cut off in a hospital, taken home and kept in a box where she’d touch them every night, and then later kept in a box the speaker finds under the sink (5B). The great gramma’s hair is literally passed down through generations.

Primal images abound too. In “Sugarfruit” a cat in heat “yowl[s]and the caged tomatoes burst, / leaking seeds onto peat moss” (13). In the same poem, a “pupa split[s]to let nightmares out” (13).

References to hunger pepper the collection – things the speaker did not have, things the ma and gramma never got. We learn from the timeline at the beginning that gramma Ruth was in and out of orphanages, and that later in life her house was taken from her. The longing and loss manifests in these poems, as “bodies pulsing with famine” (23). We see the speaker in “Animal Husbandry” wonder if great gramma Ruth “went hungry or panicked / at the grocery store, those aisles of want when / rent went steep” (18B). And later the speaker connects this worry to Ma “who also fled a house with famine / of love” (18B).

In “Lament with Tulips and Crows”, when the speaker digs a grave for the “cat who died with two newborns latched to her teats” (25B), we can’t help but recall what great gramma and gramma and ma have given up, have endured, and how they too have failed.

Ultimately, the collection meditates on how we learn to love from the women in our familial past, and how we remember them. In “Love Song with Contradictions”, love is defined not as “a boat moored on a lake / that bobs on waves, more like a house, its foundation / drilled into bedrock, that in an earthquake / still shakes. Can you explain this inheritance?” (5B). That is what the collection tries to do.

Love is inherited, invasive, and inevitable – something we are responsible for. In “Lament with Trash Night and Slugs” a dying gramma clamors to be remembered (32). And in “Freesia”, the speaker grapples with the inevitable connection to the matrilineal line:

Mother births

daughter her

unborn grand-

daughter already

curled within her… (34B)

That poem ends with a haunting question, about the sorrows and loss that are passed down: “O daughter / the knot of us – how do I unteach you this?” (34B).

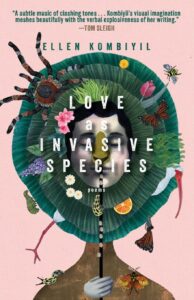

Love as Invasive Species by Ellen Kombiyil

Cornerstone Press, 2024, 70 pages, $21.95, paper

9781960329608

Katie Kalisz is a Professor in the English Department at Grand Rapids Community College. Quiet Woman, her first book, was a finalist for the 2018 Main Street Rag Poetry Book Award. She is the recipient of a 2023 Elizabeth George Foundation Grant, and her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Her second book, Flu Season, is forthcoming from Cornerstone Press. She lives in Michigan with her husband and their three children.